‘They Come From Near, They Come From Far’

By Alexander Hanimyan

The world has the golden arches, but Thornhill has the Golden Star.

Fifty-six years after the retro burger joint opened, the iconic sign continues to draw crowds daily with a lunch and dinner rush that sees lines forming out the front door onto the patio. The memorable towering sign, with its large yellow letters and four-pointed golden star on top, can be seen from afar.

The smell of charcoal-grilled meat greets customers new and old who come craving the diner’s array of fast food, from hamburgers to steak sandwiches.

The crowd on any given day or night is a mix of families, couples and singles enjoying a quick bite to eat. There is a happy buzz in the dining room for those who stay to sit and eat as others leave content and satisfied.

The restaurant, just north of Steeles Avenue at the corner of Yonge Street and Meadowview Avenue, is surrounded by multiple highrise condominiums. Its classic features, including the brown brick walls and red tiled roof, stand out among the sleek modern designs showcased by its neighbours.

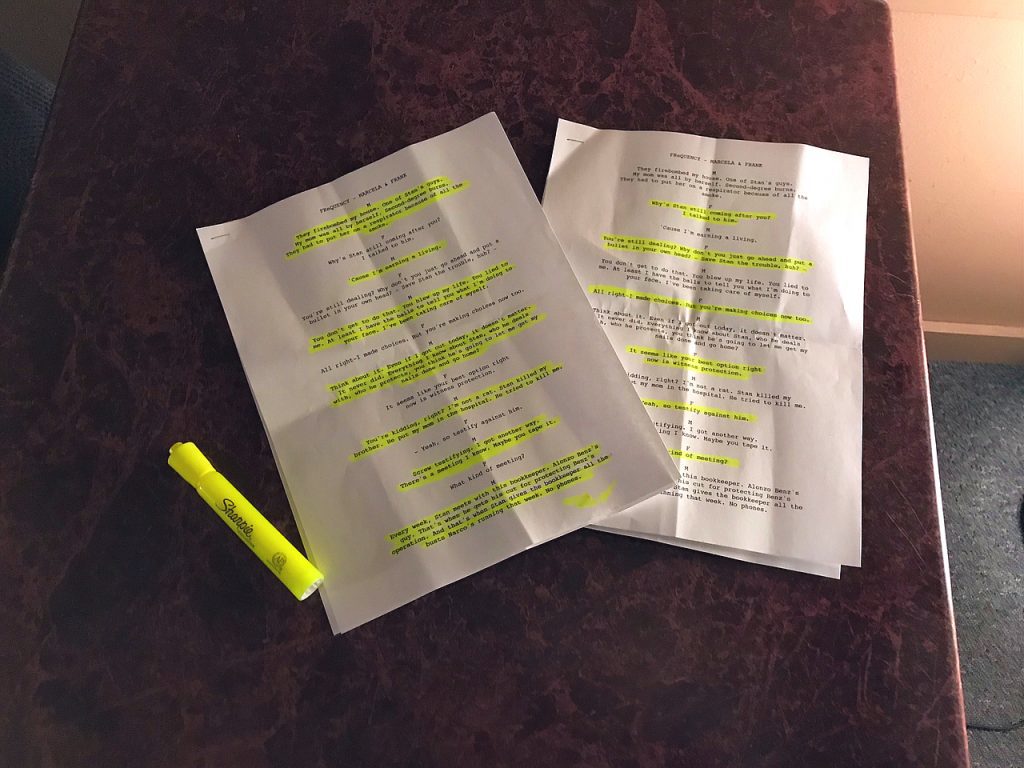

The nostalgia kicks in as the front door opens. Flashbacks to the 1960s begin with the natural wood countertop, large Coca-Cola sign and the lit menu board with yellow and orange letters. The cashier, wearing a blue button-up shirt bearing the Golden Star logo, greets every customer with a jovial, “Welcome to Golden Star. What can I get for you?”

The floor is covered with brown rectangular mosaic tile in a cobblestone pattern that wraps halfway up the wall. White stucco covers the rest of the wall. Family pictures and newspaper clippings line the wall, chronicling the long history of the restaurant. Brown plant pots hang from the drop-down white tile ceiling.

Each wooden table seats four in vintage orange plastic booths and has a 1970s-era Coca-Cola napkin holder sitting alongside salt and pepper shakers and a bottle of vinegar.

Not only has the décor remained unchanged in half a century, so has the menu: Pure char-boiled burgers with a selection of fresh toppings prepared daily, and a variety of items from steak sandwiches to buffalo-style chicken wings. The food is paired with combinations, which include french fries, onion rings or a salad. The combos are served in plastic baskets lined with black parchment paper.

It’s all one retro reminder of a time long past.

“Homemade all-star burger combo with cheese,” the cashier yells to the guy at the grill. Once the order is filled, patrons choose toppings from large steel bowls visible through a glass partition.

Golden Star is a drive up and park restaurant kind of restaurant – no drive-thru here. It’s run by the Doria family: James, Justin, Julian and Micayla, the third generation of Dorias to flip burgers here. Their grandparents, Frank Sr. and his wife Margaret, took over the property at 7123 Yonge St. in 1966 from two Greek brothers, who first opened an eatery there in 1964.

The property was always a burger joint, even before the inception of Golden Star. In the early 1950s, it was known as Wilcox Drive-In. Later in the ’50s, up till 1964, it was Biff Burger.

Frank Sr.’s sons, Joseph, who died in November 2019 at age 73, and Frank Jr., who is now 70, began working at the restaurant in their early twenties, after the family bought the property.

Joseph’s sons, James and Justin, now in their early 30s, started at Golden Star at the ages of 8 and 9 in the early ’90s. “My dad used to bring me here to wipe tables and socialize with the customers,” Justin says.

Since 2012, this generation of Dorias has been running Golden Star. James says, for years, his father and uncle Frank Jr. “would still come and bark at us and do whatever they felt was right.”

Jason Grenier is a longtime customer who first visited Golden Star in 2003 at age four. His grandmother, Ruth McDermid, who moved to Thornhill in 1963, introduced him to the burger joint.

His go-to item is the classic banquet burger. He likes everything on it, but is adamant that there can be no hot peppers.

Grenier describes Golden Star as a family-oriented restaurant that takes care of its patrons. “I find that if you are a repeat customer, you build a relationship with them. They treat you well,” he says. Sometimes, they give him extra condiments or throw in a slice of cheese or some extra bacon on the house.

“They would recognize me and they always had a big smile on their face,” he says. “Sometimes, they would even say my order for me.”

In one of Grenier’s early trips to Golden Star, he remembers the late Joseph Doria recognizing his grandmother and joining him and his brothers on the outside patio. “We were young kids and would say these almost nursery rhymes or jingles. He would say, ‘They come from near, they come from far, they go to eat at the Golden Star,’ ” Grenier recalls.

Dining at Golden Star was rite of growing up in Thornhill. “You are very proud there. It’s not very healthy food, but you are proud to be a part of the experience,” he says.

The restaurant’s ’60s-era interior is dated but Grenier believes it’s become Golden Star’s brand image: “old-fashioned hamburgers and your classic diner.”

He couldn’t imagine an updated, modern Golden Star. “I would almost be steered away from it because you don’t have that old feeling of the Star. You would think the quality of the food would change because the interior changed.”

Carolyn Reid has been eating at Golden Star since 1982 when she was 18. She had just moved to Thornhill and was looking for an old-style burger place, like Johnny’s Hamburgers at Victoria Park Avenue and Sheppard Avenue in Scarborough.

Reid’s favourite item at Golden Star is the chicken burger with lettuce and mayo and a side of onion rings. “The service is good, quick and the food is good,” she says. When she first visited 38 years ago it was a nice place to go eat with her friends. Now when she returns it brings back memories of being young since it feels like the diner hasn’t changed a bit. And that’s the way she likes it.

The restaurant sits on a valuable piece of real estate, but selling has never been in the cards for the Doria family. James says if the business wasn’t making money, it would be a consideration, but that isn’t the case.

“It’s hard for us to just throw in the towel, take a lump sum of money and move on,” he says. “Not to mention, we’ve been here a while. Everyone is happy right now.”

The décor and the atmosphere remain unchanged since before he was born. “We don’t fix anything that’s not broken. Why do it, if you don’t have to?” he says.

“We listen to our customers and they say, ‘Don’t you ever change.’ ”