By Nick Baldwin

Toby Henderson wakes up in his aunt’s house just before 7 a.m. on a Tuesday — much earlier than usual. It feels like a normal November morning, except it isn’t. At all.

The Toronto high school student is in Warren, Man., to say goodbye to his 86-year-old grandfather, who is suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a lung disease that results in long-term breathing problems and poor airflow. Kelvin Baldwin has decided he wants a medically assisted death, and his entire family — minus a few members who live in British Columbia — are in town to be with him.

Henderson and his cousin walk over to his grandparents’ home, which is attached to his aunt’s.

Another aunt and uncle are sitting on the couch in the living room, quietly talking, as Henderson enters the house. They exchange good mornings and he sits down on a chair next to the couch. He quickly dozes off — probably didn’t get enough sleep last night.

There’s a strange feeling in the air. In just hours, a team of medical professionals will arrive to “perform the mission,” as Henderson’s grandmother, Donna — who’s been married to her husband for 66 years — calls it.

Three hours later, Henderson sits in the living room with his grandparents, mother, two aunts, two uncles, and two cousins. A black SUV drives up the lane — you can sense that everyone’s hearts just dropped.

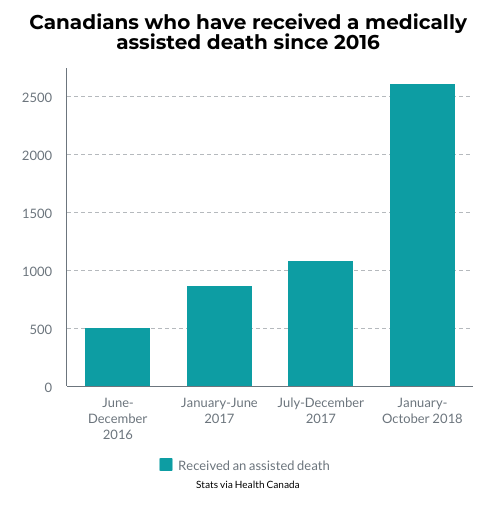

Since medical assistance in dying was legalized in Canada in 2016, the numbers of people who have received an assisted death have skyrocketed.

From June 17 to Dec. 31, 2016, more than 500 Canadians received an assisted death, according to an interim report released by Health Canada. From January to the end of June 2017, the number increased to 875 and in the following six months another 1,086 people received an assisted death. Then between Jan. 1 and Oct. 31, 2018, more than 2,600 people were granted their wish. No data has been released for any timeframe since then.

Ever since Kelvin learned that he had COPD in 2016, he planned on receiving an assisted death when the time was right, Donna says. “He didn’t want to get to a point where he couldn’t breathe on his own, or where he suffocated to death,” she says.

On Nov. 12, 2019, the time was right.

Donna greets three women at the door. They are the medical professionals who will grant Kelvin’s wish. Two are nurse practitioners and the other is a counsellor who will help the family. They smile upon entering the house, walk into the living room, and say hello to the gathered family members.

In just a matter of 30 minutes, Henderson’s grandfather is gone.

Looking back, Henderson says it was a sad moment for him and the rest of his family, of course, but that they were glad his grandpa no longer had to suffer.

“The way that I think it was most positive was in how it was for him,” he says.

“He was very unhappy, because his whole life he was an active man. With the lung condition that he had been facing over the past few years, having an oxygen tank, not being able to move nearly as much as he used to – and, by the end, pretty much not at all. All the things that really brought him joy in life, other than his family, he couldn’t really do anymore. I think he was ready. He felt as though his life was fulfilled.”

Henderson says his grandfather’s death was a smooth process. He says the night before, Kelvin’s family sat with him in his bedroom and told jokes. Kelvin told more jokes than anyone else.

While a stigma still surrounds medically assisted death in the eyes of some, there’s no doubt that more and more Canadians are choosing to die on their own terms.

Ed Weiss, a family physician who provides medically assisted deaths in Toronto, believes that has to do with the fact many people have only recently been finding out about medically assisted death for the first time. Weiss is also a board member for Assisted-dying Resources Centres Canada, an organization “devoted to providing suffering patients with a supportive, inclusive and home-like setting” for when they choose to end their life, according to its website.

“I think over the last couple years, the understanding of who is eligible has evolved,” Weiss says.

“At the very beginning, a lot of people were assuming that the law meant you had to be terminally ill to qualify. People have realized that it means someone has to be on a trajectory toward death, but it doesn’t have to be imminently happening.”

Weiss says he thinks a rise in doctors and nurses who provide assisted death has also contributed to the increase.

“At first, a lot of doctors and nurse practitioners were really uncomfortable with it,” Weiss says. “There was no official guidance on how to do things. People were really left scrambling to figure out, ‘OK, how do I get the medications, how do I get the intravenous lines started, who can I turn to for help?’ Now, there is more organized support for doctors and nurses who want to get involved.”

In February, the Canadian government proposed changes to the medical assistance in dying legislation. If passed, the bill would allow a person to be eligible for an assisted death even if their natural death isn’t “reasonably foreseeable,” according to the government website. Additionally, a person whose death is reasonably foreseeable would be able to give final consent prior to receiving an assisted death in case they no longer have the capacity to consent when the time comes.

Donna, 84, says since her husband died, she’s been very much in favour of medically assisted death – or at least the right to one – and hopes to support organizations like Dying With Dignity Canada as much as she can.

Dying With Dignity Canada, an organization headquartered on Eglinton Avenue in Toronto, advocates for the right to a medically assisted death. According to its website, the group wants to improve quality of dying, protect end-of-life rights and help Canadians avoid unwanted suffering. It also strives to support patients and educate Canadians about the options they have at the end of their life.

Donna laughs when asked if she plans to follow in Kelvin’s footsteps and have an assisted death herself – when the time is right.

“Of course,” she says bluntly.

“As a matter of fact, I wanted to go with him – you know, die with him. But they wouldn’t let me.”