By Nakosi Hunter

For roughly eight months of the year, one would be hard pressed to find a vacant outdoor basketball court in Toronto. Over the past decade the city has undergone something of a basketball renaissance, which reached its zenith in June 2019, when the hometown Raptors won their first NBA championship. But here, on this frigid February afternoon, snow is the only thing storming this Briar Hill court.

On Feb. 23, 2020. (Nakosi Hunter/T•)

“I’ve been hooping on these rims my whole life,” remarks Cassius Washington Smith, a lifelong resident of Lawrence West, located a handful of blocks north on Eglinton. “I was born just up the street.” His tone is steeped in nostalgia as he gestures toward the housing complex down the block.

“I love this neighbourhood.”

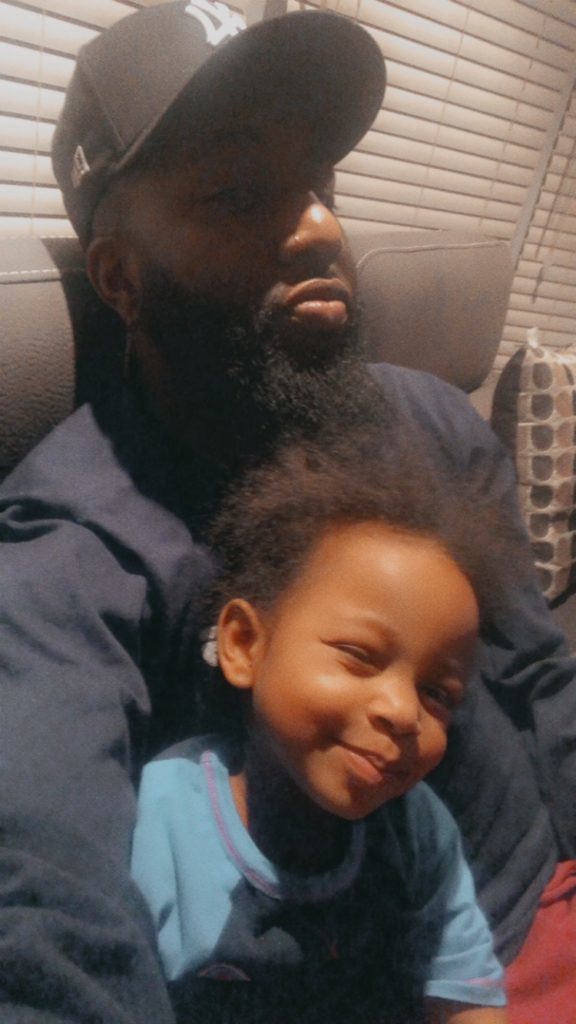

Washington Smith is a Toronto native who has spent all of his 24 years living in Toronto’s north end. Not only was he born down the block, but he is now also co-parenting his own daughter, three-year-old Luna, in the same neighbourhood as well.

“At first it was eerie,” he remarks in reference to pushing a stroller down the same streets he grew up on. “But this neighbourhood is filled with a lot of culture. A lot of interesting people, people that will teach you lessons just in passing and through conversation, and I think she’ll pick up on that in time.”

“I think this area gave me the ability to manoeuvre in any room that I’m in.”

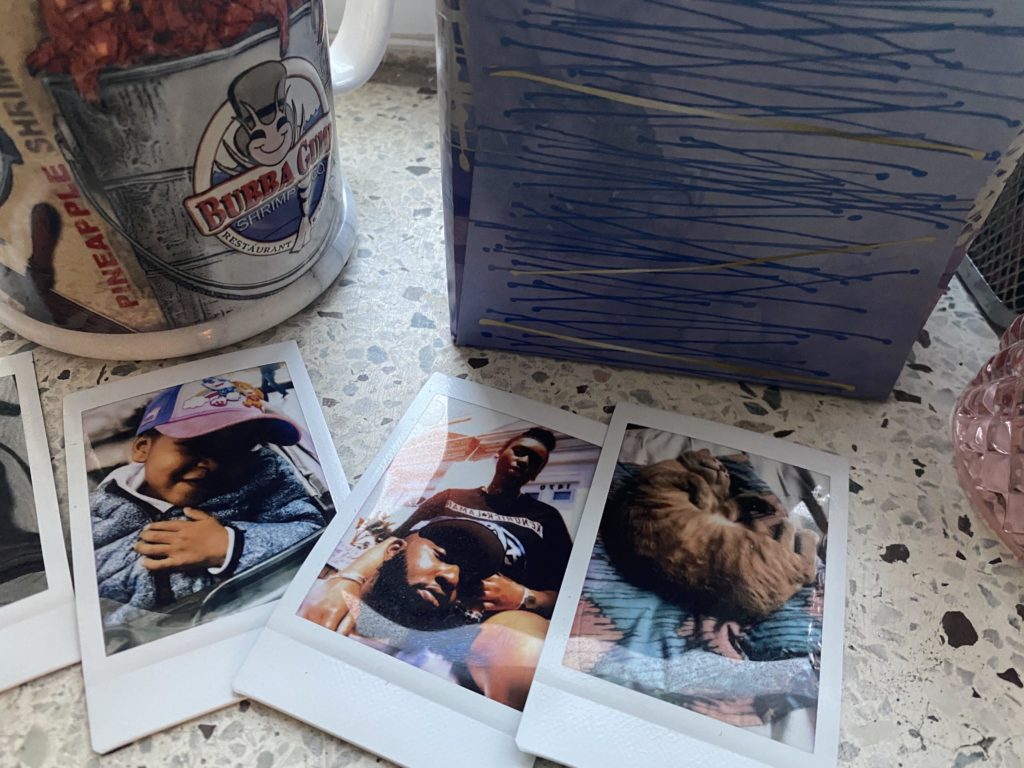

Walking toward his apartment, the final stop on Washington Smith’s brief tour of his neighbourhood, which includes his favourite bar and grocery store, he mentions he still needs to get his cooking and cleaning done in preparation for the week ahead. It is Sunday after all.

It is late in the evening by this time and the sun has taken full command of the sky, painting the horizon in shades of red and purple. The streets surrounding the court are serene, the silence broken only by the humming of cars passing by on the main street somewhere off in the distance behind the houses. If one looked only into the sky, the swooshes of the vehicles could be mistaken for the swooshing of the tide as it meets the shore.

On Jan. 26, 2020. (Nakosi Hunter/T•)

Sunset is now in full bloom and, as if it sought to light his path in gold, the orange ball at the centre of the show seems to be hovering directly along Briar Hill Road toward Marlee Avenue, where Washington Smith is headed.

In a lot of ways he is representative of urban young adulthood done right, or at least with noble intention. But to Washington Smith, stories of individuals like himself never get told.

“There are a lot of guys like me, early twenties, figuring things out, trying to go about things the right way,” he says, “but I never see that when I turn on the news. It’s always the other talking points.”

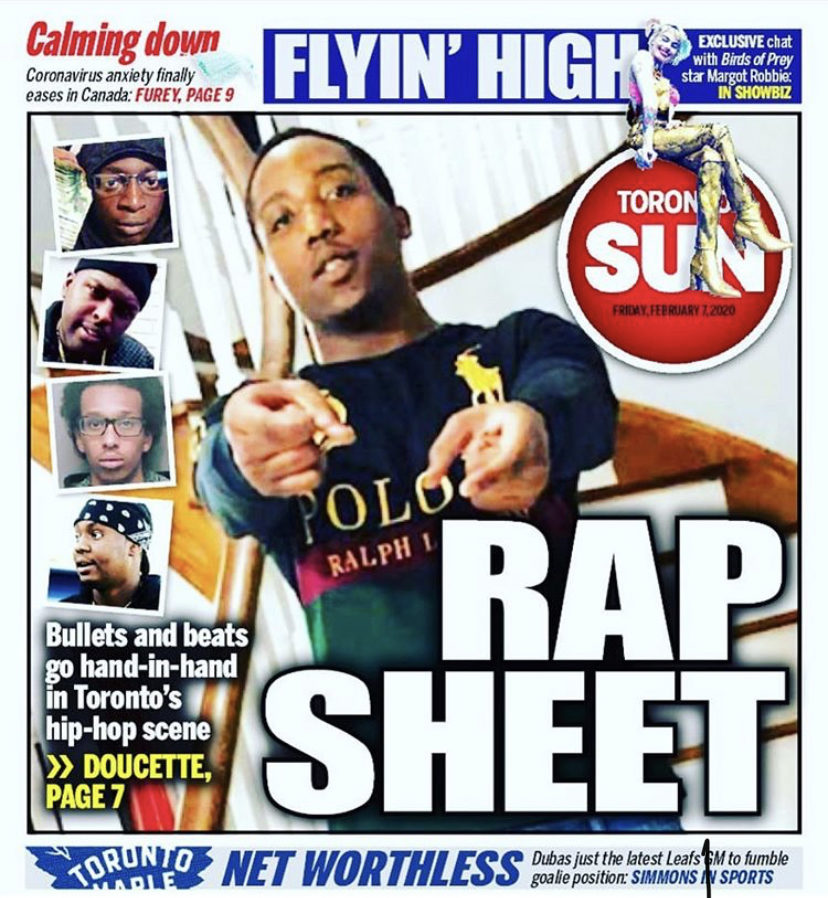

On Feb. 6, 2020, the Toronto Sun published a cover story headlined “Rhymin’ and shootin’: life imitates art for Toronto rappers.” It garnered widespread condemnation from Toronto’s urban youth for its lack of sensitivity. The story was published just a week after one of the individuals depicted on the cover had been murdered, which heightened tensions between the media and the predominantly black urban community. The Toronto Sun offices received various death threats in response and a Brampton man was arrested four days later on Feb. 10.

Sam Pazzano, a veteran court reporter for the Sun and contributing author of the story, is unswayed by the response to the story. “We dare to say what the [Toronto] Star would try to avoid because they don’t want to be seen as stereotyping things,” he says, “I didn’t create this image, I’m saying what I see.”

For Washington Smith though, the frustration isn’t that the media fabricates negative stories, but that they disproportionately choose to cover stories about violence and crime instead of the positive stories that largely aren’t deemed newsworthy to them.

“We’re not just coloured. We’re colourful, too. We have passions, we have hopes and dreams, we want to raise our kids right and make our parents proud. Some of us are achieving great things. You just wish that was newsworthy to them.”

This perspective isn’t one that has gone entirely unnoticed by those within the media bubble. Prominent black columnists, though few in number, have been sounding the alarm on this front for quite some time. Andray Domise, a columnist for Maclean’s and communication co-chair for the Black Business and Professional Association, expressed dismay at the lack of awareness within the news media in regards to their coverage of black young men.

“Even when the coverage is sympathetic it’s still all about the terrible things that happen to black boys and can they actually fix something on their side,” he says. “It’s never about ‘what are the shortcomings here?’ ‘What are the things they need?’ We don’t talk about that stuff.”

Pazzano minces no words when responding to the view that the black community receives disproportionately negative coverage by the news media. “Bad news sells,” he says. “People strive for negative stories. It’s unfortunate, but it’s true.”

“Unfortunate,” while perhaps a fitting term, leaves much to be desired in the efforts to reconcile the divide between Toronto’s news media and its urban youth.

“We’re not perfect,” concedes Pazzano. “We should cover positive redemption stories as well. I’ve done stories like that, but we can do more.”

Redemption stories matter, but it’s an angle that follows an overarching pattern of covering the black community within the context of criminal activity in one way or another, to Domise’s point. “Generally what interests people about black people is how they survive in dire circumstances, and what were the circumstances of our death,” he says.

On Jan. 26, 2020. (Nakosi Hunter/T•)

Through it all however, Washington Smith remains hopeful for representation that displays the full range of what his community has to offer. “Not that we need to be given a chance,” says Washington Smith, “but if they gave us a chance, they would see we have so much more to offer than what they show.”

In a reporting climate that often misrepresents or under-represents certain cultures and communities, Washington Smith’s perspectives reinforce a sentiment that newsrooms could be more mindful on how to cover marginalized people. As he says, members of Toronto’s urban community aren’t just coloured, they’re colourful too. And their story is a picture worth painting, completely.