By Maia-Anne Erickson

There once was a grand palace that stood tall like a spired tower. Its muted patterns of stucco were invisible amongst the bright lights of the marquee, and the buzz of the downtown core became deaf to the battle cries of twenty-somethings in spiked dog collars. In daylight, the doors of the restaurant opened, warmly inviting any and all into its restful chambers, but in the evening, everything changed. When the nightly cassette began to speak its rugged poems in the air, those simply trying to catch a bite knew to reside elsewhere. This restaurant became a club of head-banging, food-throwing, and foot-stomping mania.

If this sounds like a fable; like a tale from childhood, that’s because it sort of is. If you weren’t there to experience it, it’s a myth, and if you were, it’s a fever dream.

This palace, however, was no palace at all. Our very real parable was a place one time called “The Edge,” or “Egerton’s Restaurant Tavern.” It was an old Victorian house, once belonging to Egerton Ryerson, turned into a restaurant. At night, however, it became one of the few groundbreaking feats for the Toronto music scene of the time.

And then, like a white rabbit down the rabbit hole itself, it was gone.

The Edge opened its doors in 1979. It rose to its heroic glory and lived a lavish life until 1981, where it then fell to its fiery death like the punk community’s very own martyr. In just three years, The Edge made a name for itself that would outlive it after it was gone. The Edge is something of such renown, but this type of celebrity doesn’t come from simply existing; it’s the people within it who make it so special.

And thus, enter the Garys. One Gary Topp and the other Gary Cormier; these two became some of the most outstanding promoters in the city. Starting as a film promoter and screener, Topp first met Cormier after hiring him to do some carpentry work at a theatre known as The New Yorker. Cormier had recently escaped the music scene as an agent and had no desire to re-enter it, but following a chat with Topp and the realization of multiple similarities in taste, the two joined forces following Topp’s booking of The Ramones. When rent was raised at The New Yorker in 1978, Topp moved to The Horseshoe alongside Cormier, and eventually, when The Edge came along, they set up shop there for the next three years.

The Garys promoted as many bands as they could. They would pull artists from their own personal record collections—XTC, The Police, Ultravox; bands that they loved and would want to hear live themselves. This touch of involvement is what made the Garys who they were to be as promoters, and is a massive part of what made The Edge so special. These were bona fide promoters.

“We weren’t the kind of promoters who walked around with briefcases handcuffed to our wrists. We were involved,” Topp recalls as if it were yesterday. “It wasn’t just a job, it wasn’t just putting asses in seats, and it is definitely not what’s happening now.”

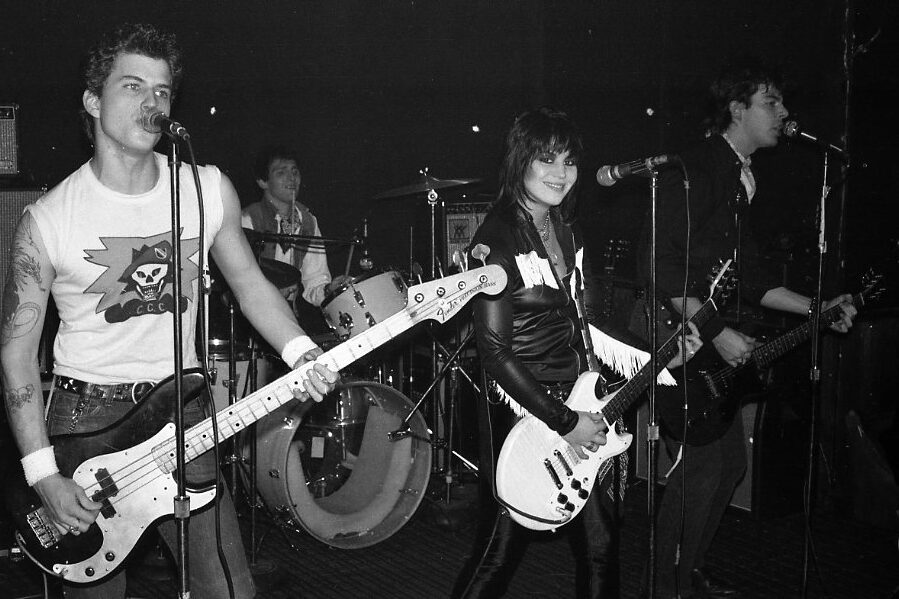

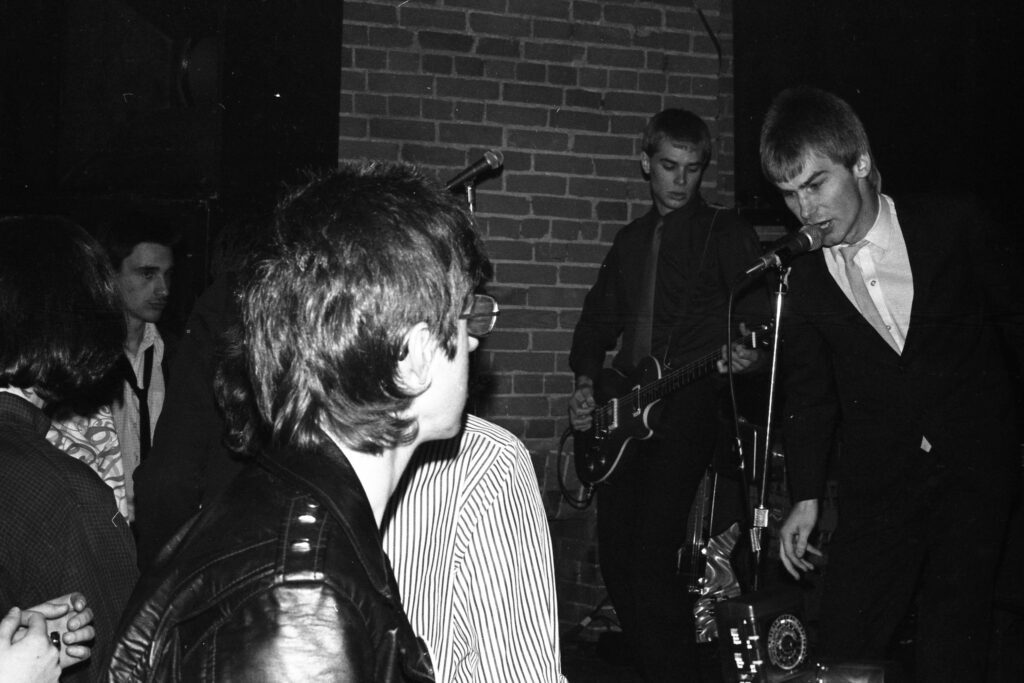

On Dec. 31, 1978, the Garys brought in both the New Year and the celebration of Egerton’s grand reopening/rebranding by hosting Martha and The Muffins as their first performers. From there, it was only an upward climb for owners, promoters, and clientele. This first performance shook the streets of Toronto. Big artists like Nico, Joan Jett, Simple Minds, Sun Ra, The Psychedelic Furs, and more, were soon brought into the tiny venue. But, with big artists, came big crowds. What stands out here is that The Edge could only house 200 people. It was tiny, but that couldn’t stop such a powerhouse.

“There was a very loyal following very quickly because they put on the bands that the industry didn’t want to touch,” shares percussionist of Rent Boys Inc., Nick Smash. “The Edge became a community.”

As a temporary busboy, fanzine curator, frequenter of The Edge, and punk-rocker himself, Smash saw the treasure of this venue inside and out. He recognized that there “was an attitude to being punk,” and suggested it wasn’t a kind one. Apart from this, he insists that even though “there’s a little bit of punk-rock antagonism, you’d see people at The Edge, and then at another [venue], and eventually, you’d become a community.” The Edge was the gateway; the place to be; the place people wanted to be. And yet, it only survived for three years.

Hover mouse for image captions.

Why, if they were so successful, would they close?

The answer is unfortunately simple. Let me paint a picture for you: When The Edge first opened and the Garys moved business over there, they worked out of their houses.

“We communicated through the air, in a sense,” Topp says. They had temporarily worked with music agency, CPI (which would become Live Nation), run by Ian and Miles Copeland, who were the brothers of Stewart Copeland, a.k.a, the drummer for The Police. Once upon a time, Kevin Coyne and Sting, the singer of The Police, had played together. So, when Topp originally booked The Police, it was because, one day, he wanted to book Coyne.

Three years later, Topp, Cormier, and, by some sort of divine intervention, Coyne are sitting in Topp’s apartment. That’s when the phone rings and Topp announces to the group that The Edge has been sold to the United Church of Canada. Topp says that it was “just time.” He was indifferent on the matter. The venue was too small and fragile to handle how big it had actually gotten. The plumbing sucked and the toilets would leak – and sometimes even rain – onto the stage. The restaurant wasn’t bringing in enough revenue during the day. It was, indeed, “just time.”

And so, Coyne played the very last show at The Edge.

“The scene was changing, so the closing of The Edge could’ve been the end, at least that’s what people said, but I didn’t think so,” Topp laughs at the drama of it all. “The real times, before things became mainstream… Those were at the edge,” he concludes.

From here, bigger venues began to open – Lee’s Palace in ‘85, Phoenix in ‘91, Massey in ‘94, and Scotiabank in ‘99. The punk community, the locals, felt and faced their fears that it was over for them.

“The Edge closing affected the punk scene. We realized not even the Garys could help us,” says Smash.

As disappointing as an ending this may seem, it doesn’t have to be. The show must go on; music doesn’t stop because the walls caved in. And so, bands did move on, as did the rest of Toronto. But the Garys don’t deserve to be forgotten, nor do the performers, or the community it made. The foundation and home of music that The Edge built from the ground up does not deserve to be forgotten.

And thus it won’t be.