By William Prowse

Snatching a great deal on the Toronto housing market is like hitting the lottery jackpot. The chances are slim, and competition is fierce. You will strike out again, and again, so your patience must be limitless.

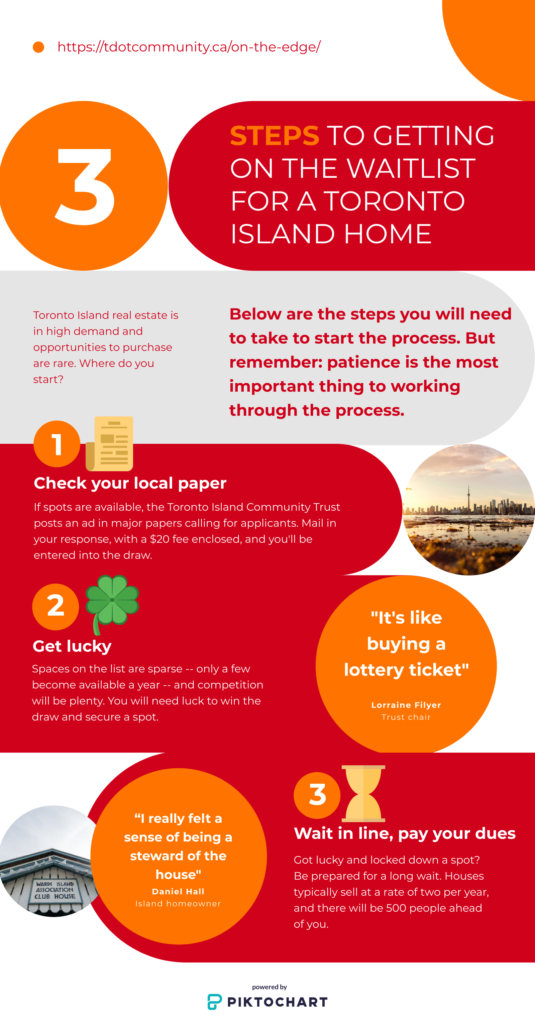

It makes sense, then, that to land some of our city’s most prized real estate, a cozy home on Toronto Island, the first step is to win an actual lottery.

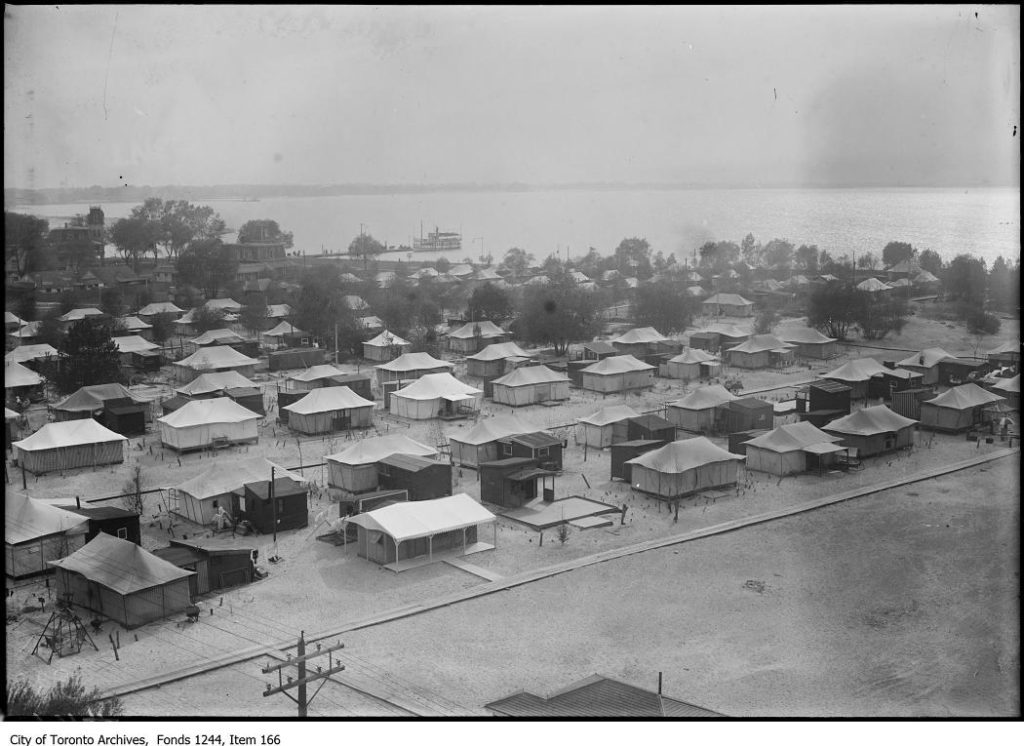

It wasn’t always so difficult. When Lynn Cunningham found her first place on Toronto Island in the 1970s, all she had to do was take over a friend’s lease.

The island’s appeal makes sense after a visit and a walk around. Go early in the morning, stand in the shade on the northern bank, and you can watch the city wake up from afar. Toronto spits out its usual din, but the wall of sound dies before it reaches the shores. You can sense noise, but it’s like watching downtown from inside a bubble.

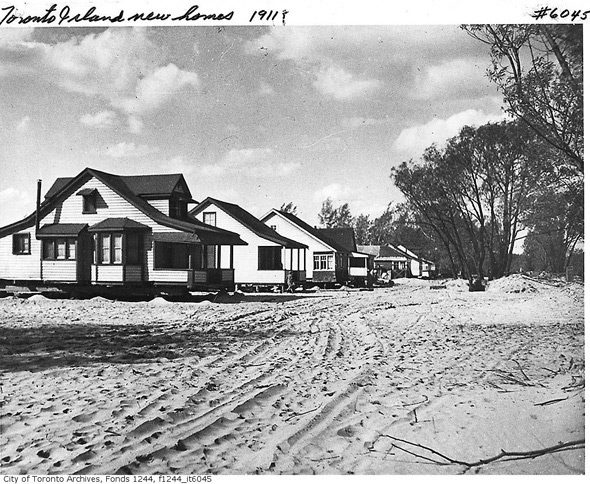

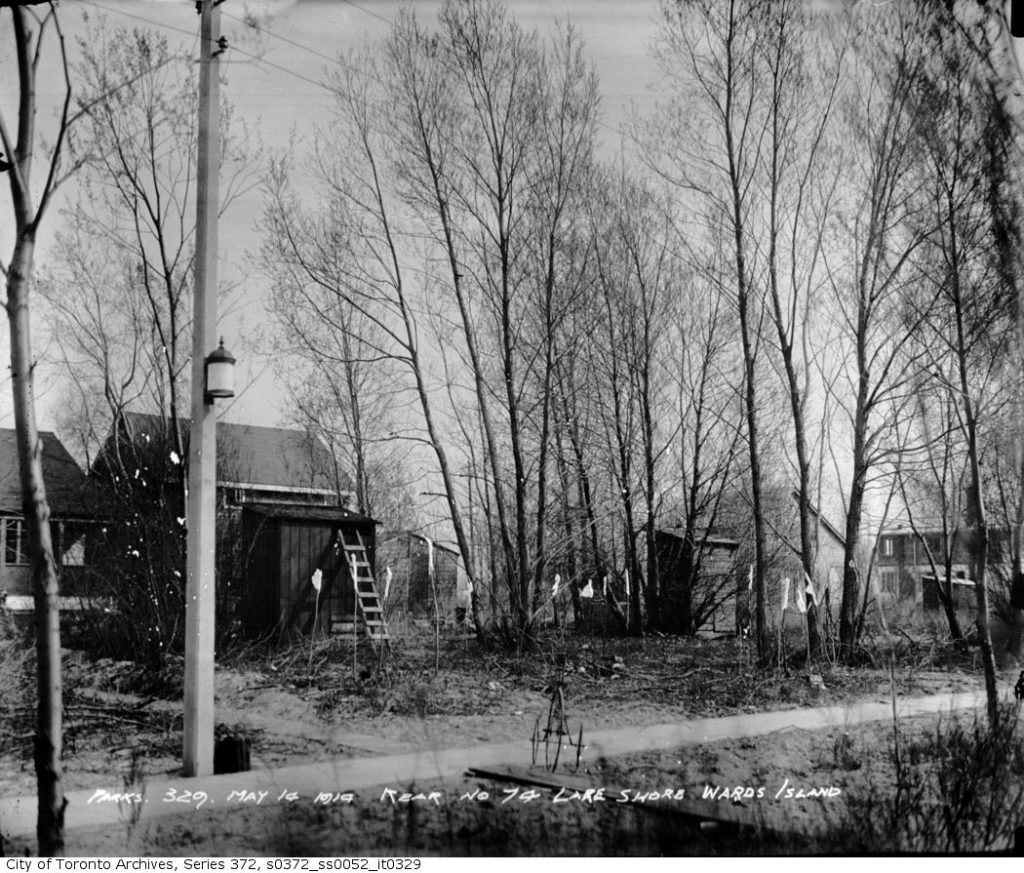

Thin streets are lined with small, cottage-like homes and yards peppered with gardens. A canopy of trees adds shady texture that speckles residential settings when the sun shines.

“I came out on a glorious fall day, and just fell in love with the island,” Cunningham said.

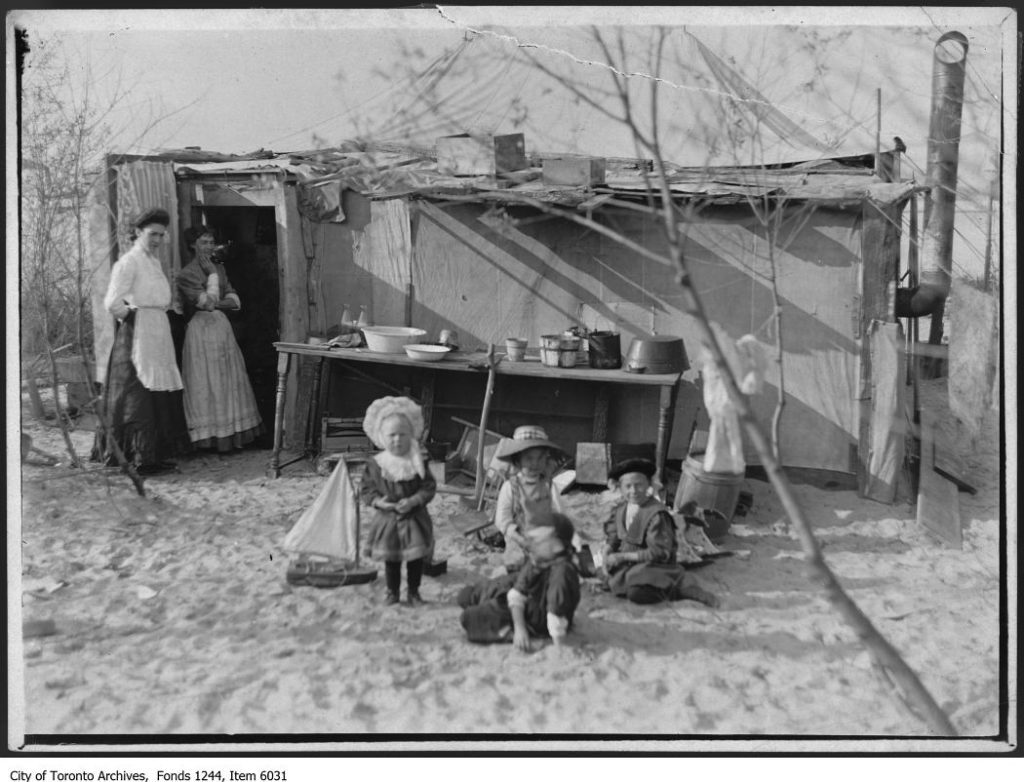

She was around 20, and just out of school. As you might expect, there wasn’t much planning involved. “We moved out with two carts of stuff, we hardly had any furniture or anything,” Cunningham said.

She fell in love with her new community. Soon after, she spent around $2000 to buy her first of several island homes over the next 40 years.

At the time, the relationship between Islanders and the city of Toronto was tense. Residents owned their houses, but had to renew short-term leases on the land under them. Metropolitan Toronto threatened to tear the homes down to make room for park space, which fueled a campaign by homeowners that spanned 30 years in total.

The battle sparked the creation of a system that has managed Island real estate from 1993 onwards: the Toronto Island Residential Community Trust.

The breezy move-in process Cunningham experienced in the 1970s is long gone, replaced with a strict system to oversee the purchase of island homes and leases. The trust irons out the buying process, and prevents windfall profits for sellers.

The houses sit on provincial land, so homeowners never own their lot. Instead, they assume a lease on it, through 2092, transferable only to immediate family members.

“Because we are on public land, we should not profit from the sale of the houses, and that’s all built into the legislation and the regulations,” said trust chair Lorraine Filyer, who is in the eighth year of her term.

When a home is listed, the trust hires an independent appraiser to value it. The selling price is based on what it would cost to replace the house, and how well it has been maintained over the years. It doesn’t matter what other houses sold for; only quality and size decide the value.

“The trust has nothing to do with the value of the house, we don’t dictate to the appraiser what it should be, because it’s all done by formula,” Filyer said.

The price is firm, and the home is offered to buyers in order of how long they have spent on a waiting list. If the price, or home, isn’t right, they can pass and hold their spot, hopeful that the next opportunity pops up soon.

Open spots on the 500-person waiting list were picked clean shortly after its introduction in February 1994. A draw is held each year to fill available spots on the list, if any exist.

No matter how great your luck is, the process will take significant time. Securing a spot on the list is no guarantee you will own an island home before you grow old, or even own one at all.

“It’s like buying a lottery ticket,” Filyer said.

Daniel Hall waited 13 years to find the right home after joining the waiting list in 1994. After four years, he had moved high enough on the list to attempt to purchase a house, but a dispute between the owner and the trust led to the listing’s retraction.

He had missed an opportunity, but Hall wasn’t anxious. As a carpenter and architect, he had an advantage: the condition of the house didn’t matter to him. He had the skills to build a better structure in its stead.

“I had also walked around the island enough at that point with a critical eye and seen that there were a number of old, not fixed up original cottage houses from the 1940s, some earlier than that. I thought, ‘Any one of those would be a reasonable enough purchase price that it’s kind of like having an empty lot and building your own house,’” Hall said.

Hall was patient. He went back to school, got a degree, and in 2005 snapped up a cottage like the ones he had eyed a decade before. It was in rough shape, unaltered after its construction in 1905 save the addition of some drywall and a few improvised renovations. He asked his boss at the time, an architect, what he should do with it: “He looked at me and said, ‘I think you should tear it down,’” Hall said.

Hall researched his home, discovering it had been floated across Lake Ontario from its original location, where Billy Bishop Airport now sits, in the 1930s. He realized he knew neighbours who lived there, including two who were married at the house. He decided not to tear it down, as advised. Though they are covered with modern materials, the same foundational walls that held the house up in 1905 still anchor Hall’s home today.

“I really felt a sense of being a steward of the house; it’s our house now, hopefully it will be my daughter’s at some point, and who knows what after that,” Hall said.The average wait time for a home now stretches far beyond the 13 years Hall spent on the list. Only 66 homes have sold since the creation of the trust system, and a community once known for its youth has now grown old.

“We hardly have any children, because the long-term residents are old, and the people who purchase houses when the few of them come up, they’ve been on the list for a long time so they’re old by the time they get here,” Cunningham said.

According to Filyer, the options to bring youth to the island are limited. Strict rules restrain rental options, and a planned co-op housing project that would have allowed easier rental access was shelved by the provincial government in 1995.

“It would have, in a way, kind of solved all those problems of having an aging community,” Filyer said of the co-op housing.

Living on Toronto Island isn’t easy. There are no stores. If you need a head of lettuce or a set of screws, you have to walk or bike to the ferry landing and take a boat to the mainland. The lake can freeze in the winter and the island often floods in the spring. These issues pack extra stress into the day-to-day lives of islanders.

And yet, the positives drown out the negatives for prospective buyers and current residents. Distance from the city you depend on can be a challenge, but for many, the distance explains the allure. Demand for the privacy and seclusion a cottage on the island provides ensures that, if you enter the draw for a spot on the list, your competition will be plenty.

It makes sense, then, that common advice from those living on the island to those who envy them is to start the process early.

“Don’t wait,” Cunningham implored.