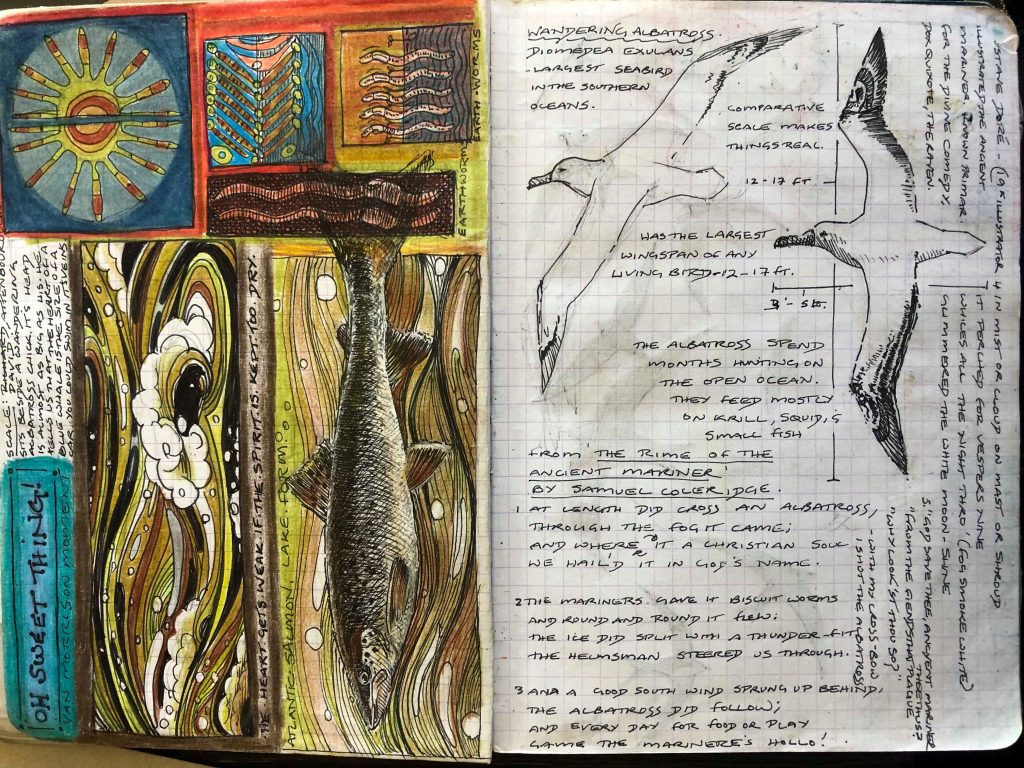

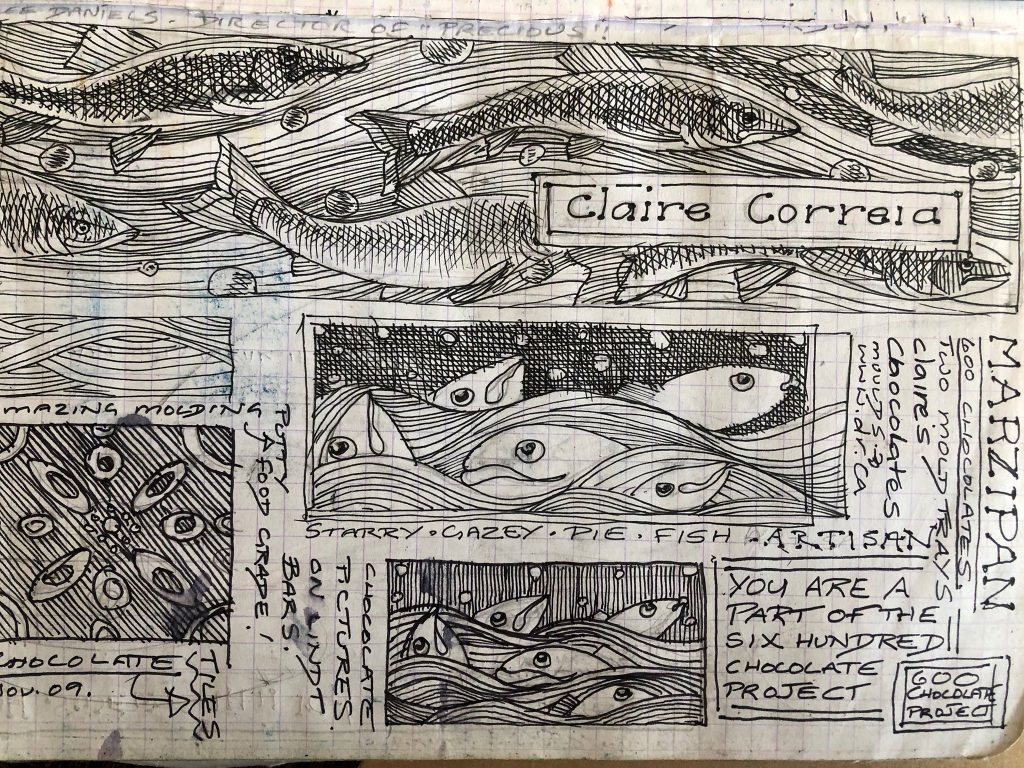

A sketch by Claire Correia, used to inspire her idea for her bench contribution to Liberty Village taken on March 19, 2019. (Shayna Nicolay/T·)

By Shayna Nicolay

Twenty-three-year-old Claire Correia enters the illegal home that she shares with more than 100 artists. She hops off her pedal bike and hoists it into her arms, carrying it up three flights of stairs to get to her “owned” space in the abandoned industrial building.

Reaching the top, she hops back on the saddle and rides down the hallways of the former factory. The hallways are vast spaces, with Victorian highlights and sky-high ceilings. Her housemates are rehearsing ‒ a band called Shadowy Men on a Shadowy Planet. Their guitar riffs, rhythmic drumming and crashing cymbals mix with the distant notes of other bands in the old, converted storage building.

The wavy floorboards make her body jolt up and down as if she was mountain biking down rough terrain. The pigeons that also call 9 Hanna Ave. home open their wings as if to imitate an airplane. They aggressively flutter their wings to take off. A chaotic cloud of birds take control of the air at the sight of Correia and her bike hurtling toward them.

She hears a strange rumbling in the distance, unable to see the culprit around the bends of the lengthy passageways. The rumbling grows louder and louder as Correia pedals closer to her room.

As she turns the corner, a man with a blue mohawk is rolling toward her on a skateboard. He’s pulled by a grown malamute husky, fixed in a harness, and they’re both coming straight for her. As Correia moves right and passes them, the skateboarder nods his head, as if this is an everyday occurrence. This is life in Liberty Village in the early 1980s.

Thirty-five years later, Correia now has a studio space at Akin Collective. Although these days she no longer lives in her small space at 9 Hanna Ave., the studios at the nearby Akin Collective are strangely similar. Correia has had her six-by-10-foot space since 2011 and shares the building with some 400 other artists.

“Liberty Village belonged to the artists before it belonged to the regular people,” Correia says. She says she has a fond connection with the neighbourhood, since it was one of the areas where she did a lot of her creative development while attending what is now OCAD University.

Correia’s age is evident by her skin, mostly through her deep smile lines. Her brown hair, speckled with grey, is braided, tied with a hot pink hair tie and still makes its way past her hips. Right above where her braid begins, a twisted silver barrette holds shorter wisps in place. Silver hoops, the size of a loonie, dangle from her ears. Despite the warm, sunny weather she’s wearing layers of clothes: black leggings, a black, white and pink diamond-patterned skirt, black tank top, a lilac purple cardigan and brown Blundstone boots – the footwear of choice in Liberty Village.

Correia is giving back to the neighbourhood that helped shape her as an artist. She has contributed to a project by Mural Routes and the City of Toronto for the installation of 14 art benches in the community. Correia designed one of the benches, which are meant to convey Liberty Village’s industrial history as well as its modern creative community.

Her contribution is based on bringing awareness pays homage to Toronto’s long lost aquaculture industry. To Indigenous people living near the water, the Lake Ontario salmon was sacred. The species became locally extinct because of years of European settlers and commercial fisheries harvesting the salmon. The return of Toronto’s Lake Ontario salmon, which began more than 30 years ago, is the result of a modern initiative, she says.

“I think that we should be much more aware of our water as part of our identity,” Correia says.

Her bench aims to criticize the industrial era of Liberty Village for literally cutting off the community’s ties to Lake Ontario.

“We’re actually amputated from the lake by the highway,” Correia says. “As attention draws away from the water, a primary source of our definition as a city, you have industrialism deciding to build alongside the lakeshore.”

She hopes her bench will help people see and think about not only Liberty’s industrial past, but the environmental past of the land it sits on. Today, condos and construction in the neighbourhood block out the views. In a city where downtown buildings dominate every corner, Torontonians often forget the original atmosphere of the city and how much residents relied on the nature around them. In the 19th century, Ontario fisheries depended on Lake Ontario for their fresh-fish markets. Eventually, the fishing trends in the Great Lakes resulted in the dwindling of valuable species, causing the less valuable species to corner the market.

The view of Lake Ontario from the Harbourfront on Monday, April 8, 2019. (Shayna Nicolay/T·)

One of Claire Correia’s sketches of the jumping salmon piece taken on March 19, 2019. (Shayna Nicolay/T·)

“It would really be good if people respond to the bench with reassurance ‒ the kind of reassurance one gets when looking at something made a long time ago. Built to last, antique but timeless in design so it could have been made in any time,” Correia says. “A lot of people don’t realize that we are actually right next door to an environment teeming with big life that’s not human.” In this case, she is talking about Lake Ontario.

Coming to Toronto in the early 1980s was a challenge for Correia since she spent her childhood in a variety of beautiful and fascinating places such as Sussex, England, north Wales and Bermuda. “Planting seeds in alleyways, keeping potted gardens in any windows available, and walking the streets with my dog with my eyes open connects me to nature, even here,” she says. “It turns out that this city actually has its own kind of wild beauty.”

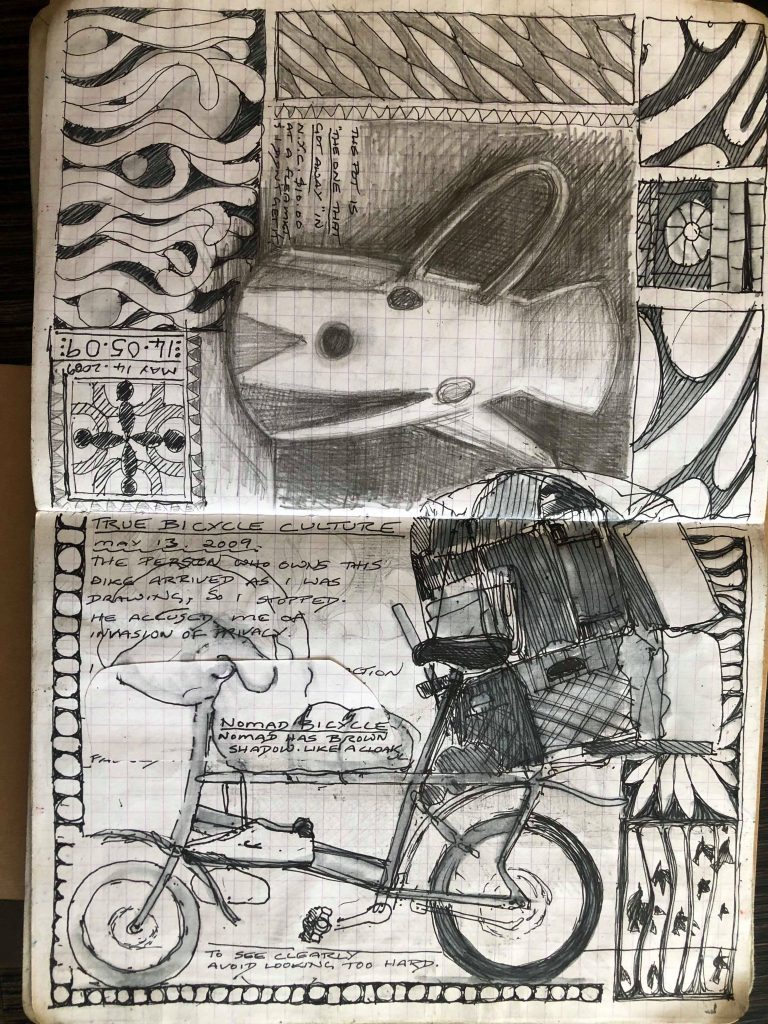

A page of Correia’s sketch book showing how she includes movement in her art, taken on March 19, 2019. (Shayna Nicolay/T·)

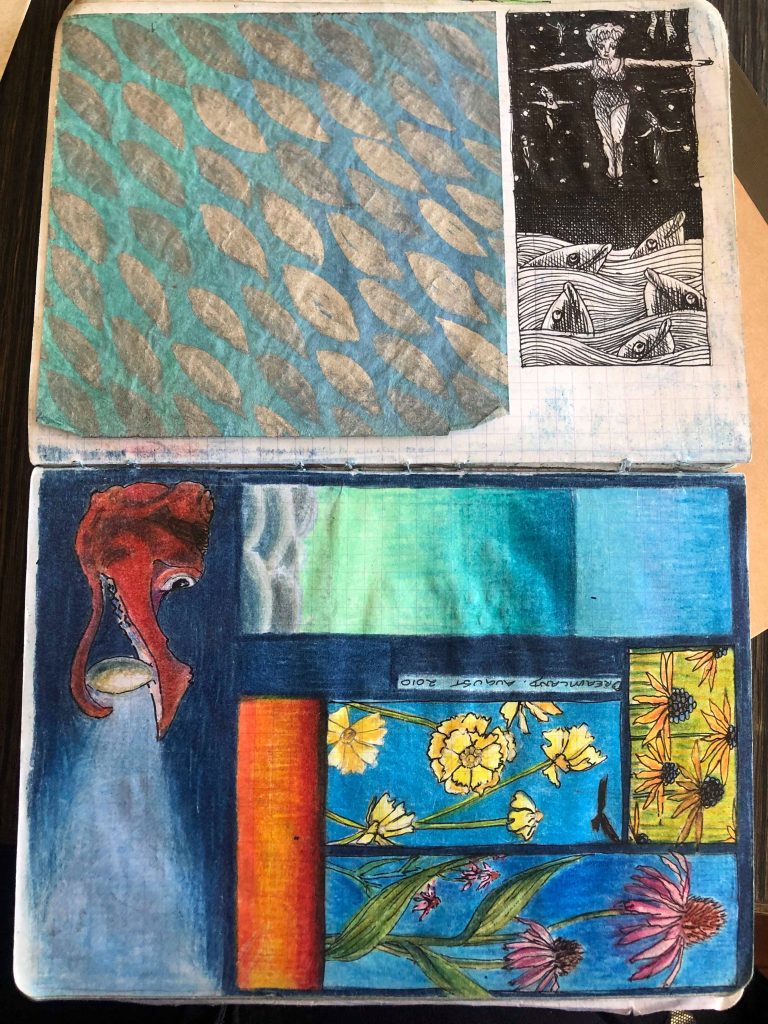

A page of Correia’s sketch book showing how nature influences her artwork on March 19, 2019. (Shayna Nicolay/T·)

When she first encountered what became Liberty Village, it was a “desolate industrial area perfect for artists.” Tattered around the edges, it was a place where you could make noise and learn from people with shared interests.

“You’re not going to wake the babies, you get to live the way you want to live,” Correia says of the old days.

Liberty in the 1980s was desolate, dusty and industrial but, “it gave artists space and we had this culture that doesn’t exist anymore.”

Between the condo construction and the tech startups, the industrial past seems like a faded spirit. The building Correia once called home, 9 Hanna Ave., became a Toronto Police traffic services facility in May 2007. Today, Liberty Village is mainly home to hipster millennials and their various breeds of dogs. In fact, according to Statistics Canada, millennials make up about 58 per cent of Liberty Village’s population. The music of new artists in the 1980s has given way to the beeping and groaning of cranes, the pounding of jackhammers and screeching of concrete saws.

Correia says many buildings in Liberty Village had “nobody but pigeons living in them— pigeons, artists and musicians. It was dark but it didn’t feel like danger.” Those days are gone forever.