By Mariyam Khaja

Within her first week at the Redline Coffee and Espresso Bar, a café in Toronto’s Moss Park, newly-hired chef Siobhan Sintzel met a man she calls Pete.

He walked into the café one morning, muttering with his arms flailing, as he usually did, sporting a pair of blue jeans, running shoes and a ratty t-shirt. He’s a bald, wiry man in his late 40s with missing teeth, ravaged by alcohol, methadone and heroin addictions that made him seem older than he really was.

“Uh, can I have some coffee?” he asked. “I got a tab.”

Over the years, Redline has become a community hub to the many Pete’s that exist in Moss Park, fueled by owner Julie Van Der Lugt’s vision of equality, regardless of her customers’ socioeconomic status. “I had to decide if I was going to accept it or fight against it,” she says, referencing the homeless population within the neighbourhood.

“I chose to accept it and welcomed everyone into my café.”

Nine years later, that vision has manifested itself into the fabric of this place. A two-minute walk from the local shelter, Redline isn’t bothered by the city’s homeless crisis in its backyard, nor the challenges that come with it. In fact, it has embraced them.

Those that can’t afford food here are given it for free or have the option of paying off a tab. On brisk winter days, the café welcomes the homeless seeking refuge from the cold, while an open library near the kitchen offers a way to pass the time.

For Toronto street nurse Cathy Crowe, spaces like Redline offer a respite from the stigma she’s seen around homelessness, especially given its “worsening state” within the city. According to recent data from Toronto Public Health, 145 homeless people died in Toronto between January 2017 and June 2018, the lack of shelter beds being one contributor.

Many shelters operate beyond the recommended 90 per cent capacity, says Crowe, making them “intolerable” breeding grounds for bed bugs, illness and disease outbreak, like streptococcus A. Full capacity shelters leave the homeless with second tier systems, including respite centres and 24-hour drop-in cites. But Crowe says these spaces are often overcrowded and afford little privacy, resulting in theft and cases of physical and sexual assault.

Left with few other options, those who are homeless often end up back on the streets, subject to the discrimination Crowe’s witnessed too often in her line of work: “People have been urinated on, beat up in bus shelters, and had their encampments set on fire- it’s disheartening.”

At Redline, policies embody Lugt’s belief that the homeless deserve to be “treated like humans.” That mentality has became an integral part of the hiring process- she ensures their “skeleton staff” are accommodating of the homeless and mentally ill in the neighborhood.

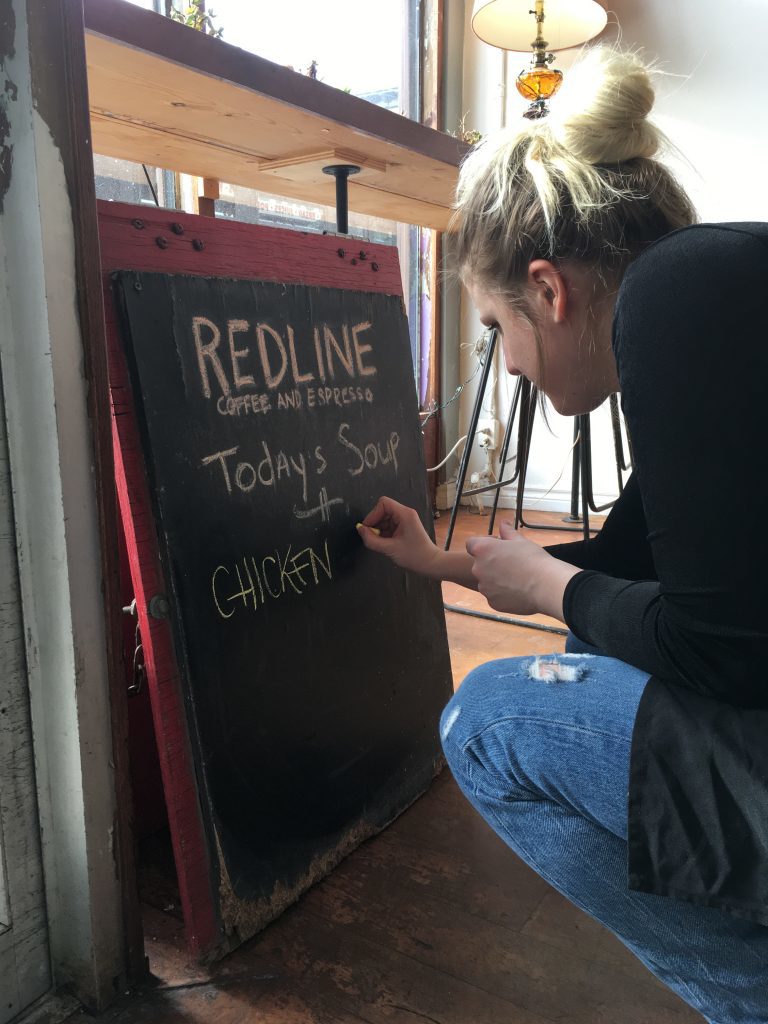

One of two baristas at the cafe, Emily updates a chalkboard sign with the day’s lunch specials. (Mariyam Khaja/T·)

Emily washes dishes at the front of the cafe after serving customers coffee. (Mariyam Khaja/T·)

But most here are used to Pete’s ecstatic behaviour already – he pops into the café multiple times a day yelling out reports gathered from his self-proclaimed post as community watch guard. His morning coffees and Sintzel’s signature banana bread are added to his tab, which he religiously pays at the end of each month upon receiving his welfare cheque. His presence at the café eventually led Lugt to hire him as a temporary cleaner, a practice she started to help the marginalized feel a part of their community.

In her three years at Redline, Sintzel estimates that one-third of their staff has come from the streets: there was Tim, a chef hired from the addiction program at a local shelter, then Rachel, a woman struggling with an alcohol addiction in her late 30s, then Pete, and still others that fit the mold. While Lugt says these have been “mostly successful” hires, they come with their own set of challenges.

Six months into his work term, Pete became increasingly violent towards staff and customers, returning to what Sintzel coined his “addict behaviour,” and forcing her to let him go.

“He’s had it really rough,” she says. “But we’re a café, not a hospital or a halfway house.” She catches a glimpse of him around the neighbourhood every now and then.

“He doesn’t want to be like this,” she says, smiling fondly. “He’s got a good heart.”

The intimate relationship between Redline staff and its customers extends beyond Pete, into what Sintzel describes as an “accidental circle of care” for Moss Parks’ marginalized. Social workers from the area drop by Redline to exchange information on those that are a part of the local shelter system, but who also frequent Redline- like James.

About a year ago, James was in a group living program at a local Moss Park shelter but would often go missing. He would make his way around Moss Park, strolling into Redline five or six times a day.

It was only after he stopped coming by did Redline staff notify one of the social workers familiar with his case. “The next thing you know, we have people going out and looking for him, because he could be anywhere,” says Sintzel- in jail, in another shelter, or back on the streets. Often times, she says, the homeless have few others willing to look out for them.

“People who wouldn’t get that kind of treatment anywhere else get it here,” she says, smiling over her shoulder in the small of Redline’s kitchen, crowded and tucked away in the back of the café. She hums to herself softly, shuffling her feet every now and then, to the strains of Alphaville’s Forever Young echoing through the café. “I love that that’s who we get to be in the world.”

The two rest against the kitchen doorway, chatting about a local shooting last night that left the café taped off into the early morning hours when Sintzel arrived ready to begin her day. Running a business in this neighbourhood comes with its own setbacks- having police tape around your workplace is just one.

There are the needles that clog up the toilet. Patrons that throw coffee at baristas. Men and women who smuggle drugs into the bathroom. The gentleman Sintzel must remind to close the bathroom door before relieving himself. The homeless man with matted dreadlocks who careens in once a week to steal the tip jar, only to retreat when he’s failed and return again with hopes for greater success.

Although the growth of the business is limited by the clientele and community surrounding the café (it’s certainly not a “destination spot,” as Sintzel puts it), Lugt says she has no plans of relocating elsewhere.

“What we have here,” says Sintzel, chuckling to herself, “it’s a full-service job.” And she takes it all in stride, keeping entertained by talk of UFOs and extraterrestrials she’ll inevitably hear throughout the week.

“We fumble with a lot of things, and we’re not always well-supplied, or everything we need to be,” she explains. But none of that matters to Sintzel, because even on the strangest of days, and there have been plenty here, Redline will always leave its doors open to the Moss Park community- no matter who walks in.

“And,” she says, “that’s what makes this place work for me.”

UPDATE: T• was sad to learn late in 2019 that the Redline had closed. It will be missed.