By Sophia de Guzman

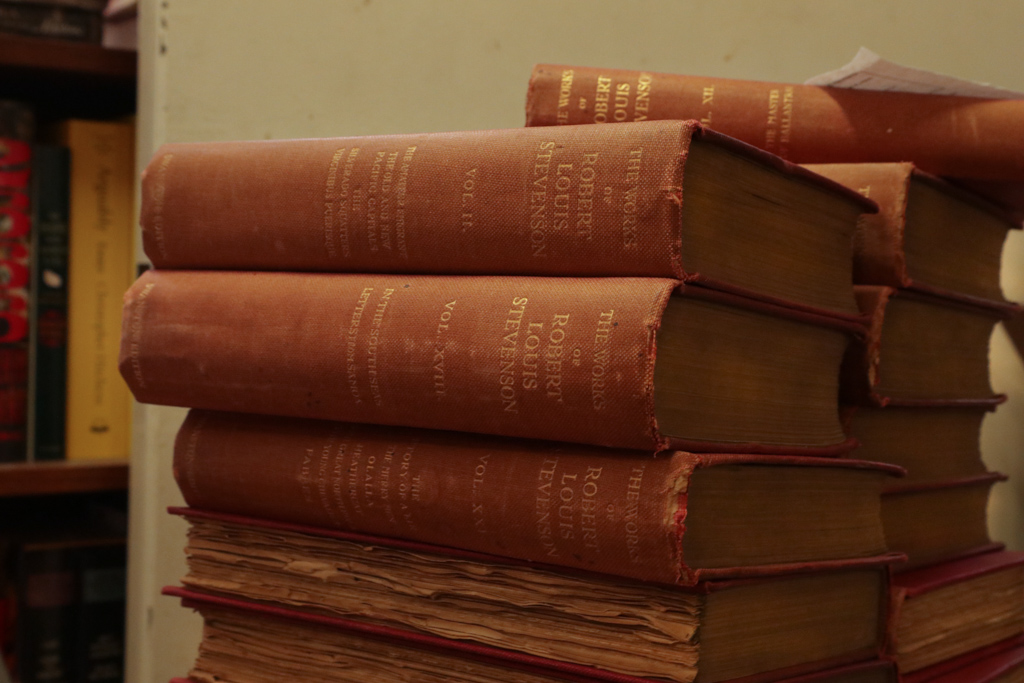

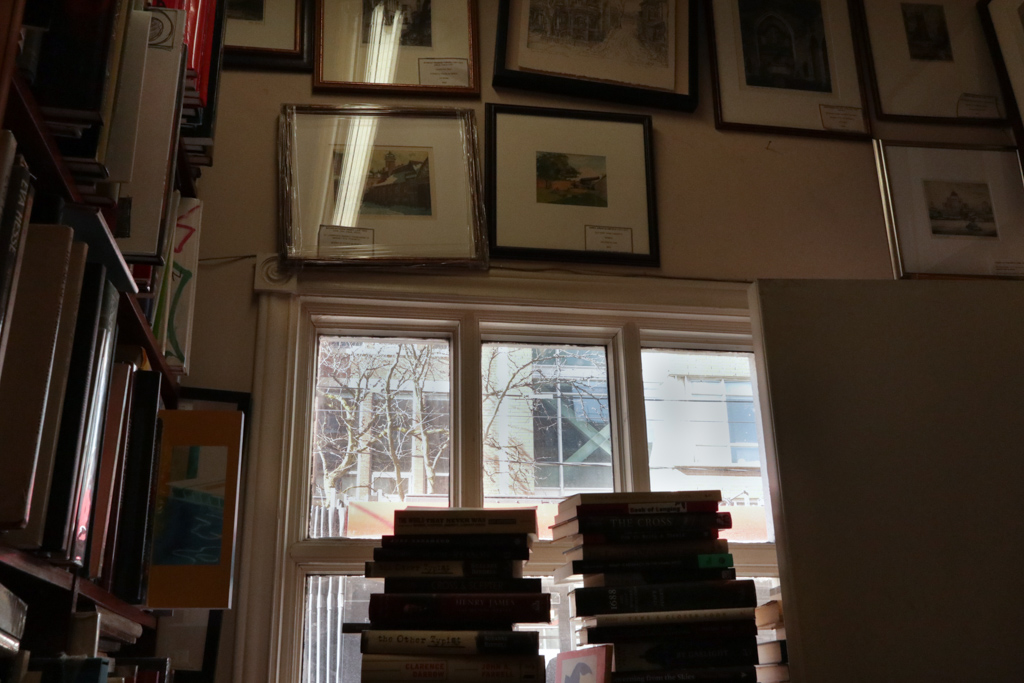

The inside of D&E Lake Ltd. looks like it was pulled from the pages of an “I Spy” book. All who enter are tasked to find a clear path to browse the tight space, as though any sound would disturb the delicate and precarious placement of everything. Shelves filled with books of all sorts take up most of the store and the walls are coated in paintings, maps and letters.

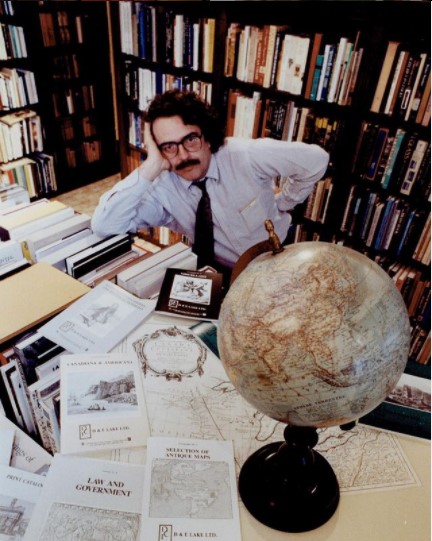

Like moss, piles of books have grown on any surface that will sustain them — including the front desk where Don Lake, one of the owners and operators of the store, typically sits. He doesn’t wait until he’s emerged from behind the paperback barricade before he greets visitors, asking if he can help with their search today. While speaking, Don expertly navigates obstacles, pausing in between obscure book recommendations to tell the visitor where to stand to make room for him to sneak by.

Don, along with his wife Elaine and their family have run their business from the same unit five minutes from Toronto’s St. Lawrence market for the past 40 years. They are members of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of Canada (ABAC), and preside over a large inventory of books ranging from early prints to Canadiana/Americana literature.

“I really couldn’t care less about cash. I love inventory,” Don says, grinning as he begins to sort a large pile of books, “Some of my colleagues don’t feel that way.” He doesn’t care much for new things, either, although he points out that he has the means to be driving a “very nice” car.

“I also do the stock market, which is my form of liquidity,” Don says. “I love capitalism, and I think I’m not bad at the sport of capitalism.”

He and his wife have done well enough for their family to buy their building on King Street East to work and live in. That is, until a fire devastated the third floor shortly after they brought the place and only the store could stay. Owning the premises has been critical to their survival as Toronto’s retail rents have continued to climb since the Lake family made their purchase, A strip of Bloor Street to the north even cracked the top 10 of the most expensive retail rents in the Americas, ranking fifth on a 2019 list compiled by global real estate agency Cushman & Wakefield.

Walk towards D&E Lake from either direction on King Street East and the worn blue wooden storefront stands out against the sleek and modern architecture that covers most of downtown Toronto. The contents are equally incongruous in a world increasingly dominated by e-readers. The first e-readers came out in the 1990s but with the release of Amazon’s Kindle in 2006, e-readers were solidified as a contender to replace physical books. A 2020 study conducted by BookNet Canada, a non-profit organization formed nearly 20 years ago to provide technology and research to help the book industry deal with “systemic” challenges, polled around 1300 Canadians and found that 45 per cent of participants read digitally only. Small independent bookstores like Don and his family’s have had to adapt to the times.

BookNet also found that the main reason people choose independent bookstores over digital is the feeling of being in a physical bookstore. As Toronto marches into another wave of lockdowns to control the spread of COVID-19, this is easily understood. .

“I think everybody needs a physical bookstore in their community to, you know, leave your worries at the door and just get lost in the books,” said Justin Wood, another member of ABAC and owner of The Scribe Bookstore in Toronto, “It’s kind of in our nature.”

Wood is not alone in thinking this. In another study from BookNet Canada revealed that three of four small independent bookstores in Canada have a positive outlook on the future of their shop.

The Lake family is adapting. While they work through their physical location, they also meet with clients online from around the world. Unlike the old days, they don’t need to travel to exhibit their collection. Back when they did fly from place to place, Don says he never travelled as a tourist — he was always working, looking for the next great addition to their collection.

One of his lasting memories from those days is the paperwork that comes with crossing international borders to buy and sell expensive antiquarian books. It could get overwhelming and mistakes were costly. This is why Don says he and Elaine will probably never return to Italy.

The defining document from their last trip there, in 1994, was a carnet. This document meant they would not have to pay duties or taxes on merchandise that would enter and leave the country within a relatively short period of time, usually 12 months. They understood that when travelling through the European Union, one could open a carnet in any country and then move freely through the E.U.

“That’s not the opinion of the Italians,” Don scoffs.

Don and Elaine knew they did not have the time for stricter restrictions that demanded opening up a whole new carnet just for entering and exiting Italy. So between exhibits, Don squeezed in meeting with a minister of culture to open the Italian carnet but, as he told a Swiss antiquarian bookseller a short time later, he didn’t intend on making his 9 o’clock “close-the-carnet” date with the minister before their connecting flight from Milan to Frankfurt. The man had only one piece of advice for him: “Don’t come back.”

Thankfully, this kind of paperwork is no longer much of an issue. D&E Lake now makes most purchases and sales online, selling from their site catalog and bidding in online auctions.

Don turns to the wall near the back of the store, examining a collection of framed Swedish bookplates. They’re some of his favorite items in the store, but he laments that they have never been popular with customers.

Just then, the door to D&E creaks open and a man in a long dark coat shuffles in carrying a plastic bag, the bottom threatening to split under the weight of the many paperbacks inside. He silently puts down his bag and hovers around the smaller piles of books at the front and Don makes his way over. He doesn’t greet the man either, but when they speak, there is a familiarity between them. Don dives into the bag of books and begins sifting through right at the doorway, seeming to not care about the possibility of another customer walking in.

As the two men hunch over the oversized gift bag, Don begins to name prices for each book. All of them are under five dollars, with some being assessed as worth nothing at all. At every mini-book appraisal, the other man subtly contests at the price. They stand, haggling over the paperbacks for a few more moments. Don finally lets out a sigh and offers the man a number that sounds a few dollars higher than the sum of all the books appraised. As the number sits comfortably under thirty, Don is willing to give a little. Still, the man sounds displeased with the small wad of cash in his hand. He nods at Don in what will shortly appear to be his version of “goodbye” and shuffles back out the store.

Don returns to explain that all kinds of people come to the store. And he is always willing to leave the door open.

“[Being] a bookseller, my real duty is to try to make sure people read good books,” he says earnestly. Don eases back into the chair behind his desk and his wall of paperbacks, and begins to sift through everything he needs to do that day.