By Libaan Osman

Sitting in his office at a community centre in Moss Park, Kevin Jeffers—a recreational programmer and a godfather of Toronto basketball—stares directly into the eyes of Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant, smiling at the NBA legends who grace the poster taped to the top of his desk.

His luminous white smile radiates the fairly sized room that’s painted half yellow, half blue as he reads the quote on the poster glancing away, almost as though it’s engraved in his 44-year-old bald, shiny head: “If somebody’s not obsessed with what they do, we don’t speak the same language.”

Listening to Kevin speak, there’s no question that obsession is what’s kept him around the game so long: for about three decades, he’s been coaching, learning, and teaching what basketball means to hundreds of teens and young men across Toronto. He’s engrossed by the flick of the wrist on a smooth jumper and enraptured by the squeak of a sneaker on the hardwood, but most of all, Jeffers is obsessed with coaching the youth and helping young men dribble out of the hood: it’s an obsession that became a lifelong career.

It all started in 1992. Jeffers was just 17 when he got a gig coaching 12-year-olds in the Regent Park area; it was the first work experience he ever got and probably the best he would ever get. With a football background growing up, coaching allowed him to bring toughness and demandingness to the sport, getting the best out of his players and giving them a role model at the same time: seeing a 17-year-old taking his future by the reins was not as common as it should’ve been.

Most of the youth he coached live in Toronto Community Housing and surrounding areas, where the echoing sound of gunshots—pop, pop, pop—was more common than politicians acknowledging that they existed. To Jeffers’ excitement, the players responded to his coaching style with remarkable verve.

To many of the kids from Regent, the only way out the ‘hood was either through rapping or making a name for yourself on the local courts. Basketball was an escape route, and Jeffers was more than willing to point the young men in the right direction.

“Dribble out of it or rap out of it, which one? Jay-Z said it best,” Jeffers says. “I’ve been to Italy three times. Why? Through basketball.”

He garnered a name for himself as one of the best inner-city coaches, and soon, an opportunity to join the staff of the storied high-school program at Eastern Commerce Collegiate—one of the top basketball clubs in the city—sprung open in 2001.

“I began kind of just doing my little bit of research on him and everything that came back was positive,” says Roy Rana, then the head coach at Eastern. “He just has this kind of sparkle in his eyes–this spirit to him–that jumped out to me.”

Over the years working together at Eastern, Kevin and Rana turned from colleagues to becoming hand-in-hand. Rana with the x’s and o’s and Kevin pushing guys to their extreme limits, getting the best out of them whenever they hit the court.

When Rana left Eastern to take the men’s head coaching job at Ryerson University in 2009, the keys to the program were handed to Jeffers, and it became his baby.

It was the heyday of high school basketball, Jeffers recalls. Every year, Eastern would consistently have about 60-80 kids eager to try out for the team, and the school went to four straight provincial finals, an unprecedented level of success. Some of its players made it professionally. They dribbled out of it.

One of the best players to come out of the Regent Park area was Ammanuel Diressa, who played for Tennessee Tech University of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) before rounding out his university career playing at Ryerson. After graduating in 2018, he signed a contract to play professionally in Serbia.

“When a lot of people didn’t really believe in me as a basketball player, I trained with Kevin growing up,” Diressa says of his former coach. “He saw my work ethic, he invested time in me, continued to push me.” That made a massive difference, he adds.

But in 2016, Eastern Commerce was forced to shut down due to low enrollment and funding cuts. The storied team that once had 80 players trying out, was undermanned with a roster of nine in its final season. At long last, Eastern had gone south.

The writing was on the wall for years, Jeffers says. He saw it coming—it was hard not to as funding dwindled—but he couldn’t bear to leave his students behind. “You just look at the kids and you’re like, ‘One more year,’ and one more year turns into another year,” Jeffers says.

He spent 15 years of his life there, taking everything in: the quiet walk from the parking lot to the gym, swinging the red doors open and feeling the dribbling of the basketball intensifying as he neared the court, louder and louder with every step he took. As he got closer to the small, dingy gym, he was home. Accomplishing everything he set out and with his two kids Kenyon and MaKenzie six years old at the time, he was internally in a good place and ready to retire.

But the phone calls, and text messages from players wouldn’t stop. Everyone wanted to know where Jeffers would coach next. The youth in the neighbourhood needed their commander-in-chief; they needed their godfather.

And next thing he knew, he was getting a tour of Central Technical School, right outside of Bathurst station.

Walking through the dilapidated gymnasium that had tar hanging off the ceiling, it wasn’t perfect, but it was something he could work with. He was obsessed all over again, having a place to coach the youth and help them choose to dribble.

A gymnasium is much more than a shimmering floor with baselines and free-throw lines to Jeffers. “It’s my escape from reality,” he says. “It brings me into another world, and basketball is that world, and it just makes everything normal.”

Omar Brown, a former player at Eastern who became Jeffers’ assistant later on, didn’t hesitate to join him at Central Tech. “He’s one of my confidants. I’m going through things—he’s been there,” Brown says. “It’s more than just basketball. He’s a brother of mine.”

Those that he’s coached will come to his office, not for pitstop but to pay homage to a man that believed in them when many wouldn’t look twice their direction. They reminisce and laugh about the long gruelling practices they went though as if it was yesterday.

“In many ways, he’s the last inner-city guy coaching inner-city kids, and trying to really change lives,” Rana says.

“If they had a hall of fame in Regent Park, he’d be in it.”

The trophies in his office at the rec centre span about three decades. If you ask Kevin how much titles he’s won, he won’t be able to answer you. He’s lost track of the number of city championships he’s hoisted, but to Jeffers those are meaningless.

What, then, means something? It’s the group chats he’s in with former players, where they share videos of them dunking through the roof; it’s seeing young kids turn into men.

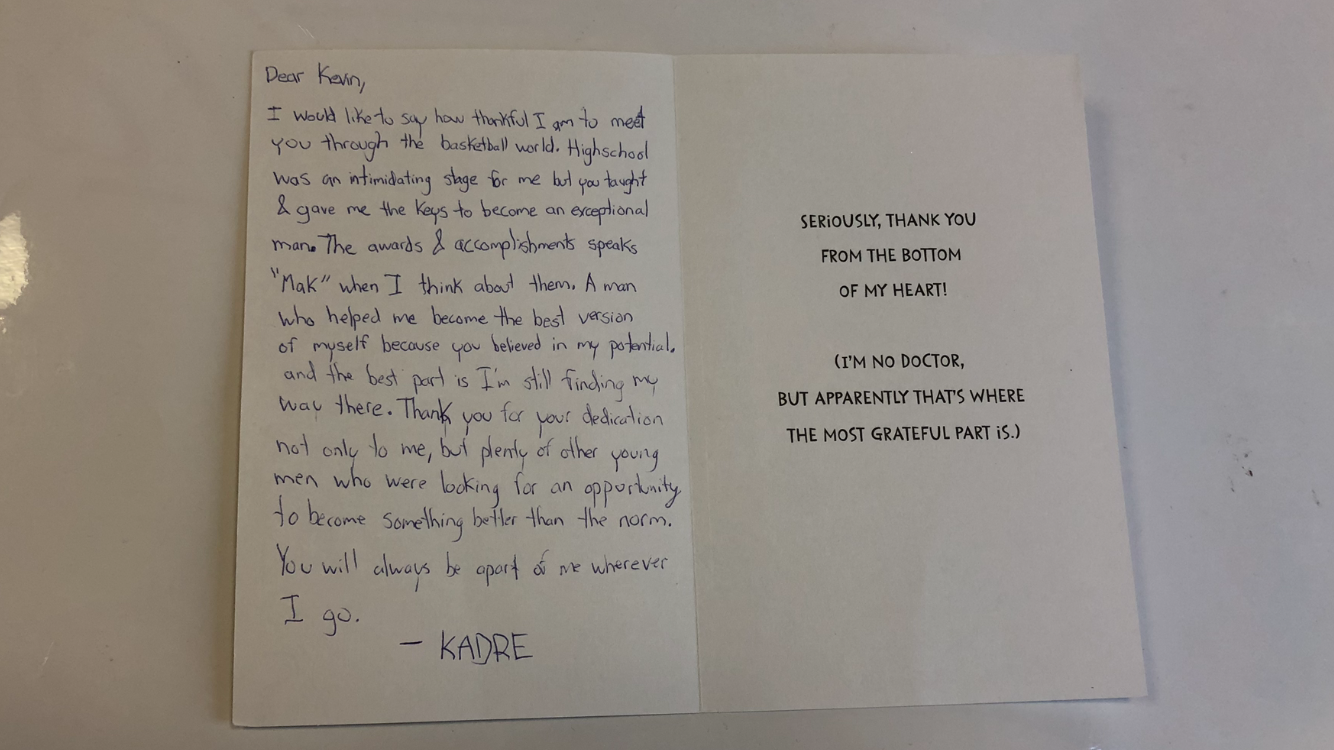

Former player of Jeffers, Kadre Gray of the Laurentian Voyageurs, chose the rec centre as the spot to hang his banner of accomplishments in the Canadian University Sports league.

A letter from Gray that is still in perfect shape lays on his desk as he passes it over like it’s his most prized possession. It writes: “High school was an intimidating stage for me but you taught and gave me the keys to become an exceptional man… You will always be a part of me wherever I go.”

That’s how every single player that had the privilege of rocking a jersey on his behalf feels when you mention his name. Their careers live on through Kevin, like a godfather always looking over.