By Trevor Popoff

As couples gaze at Toronto’s hazy skyline from one of the Don Valley’s many lookout points on an unseasonably warm February afternoon, a child examines a fresh dog print in the mud. Meanwhile, a couple of mountain bikers whiz by on the trail beside her, their tires cutting through the fresh slop. A mother and her son wander down the old railroad tracks, scars left behind from the days of heavy industry in the valley. The boy stops and balances on one of the rails, holds his pose for a moment, and tumbles to the ground.

As Brent Raymond (you’ll meet him later) points out, “the Don Valley can be different things for different people.”

He couldn’t be more right.

The Past

Floyd Ruskin recalls the moment he knew he wanted to see the Don restored to its former glory. On a field trip he helped organize for his daughter’s class in 1989, Ruskin, his daughter and his nephew planted four white pines on what was then a barren hillside just north of Riverdale Park. “Every time I walk past, I take notice,” Ruskin says. “It was a great day.”

Ruskin is a hands-on type of guy. Sharp-witted and astute, Ruskin has spent four decades studying the history of the Don Valley. In the ‘90s, Ruskin was a key cog in the Taskforce to Bring Back the Don, a not-for-profit that yanked the valley out of its industrial past. He visits the valley every single day.

As most things do in this country, Ruskin says, the story of the Don Valley starts with Indigenous peoples. The Wendat passed through the valley for centuries, coming for the bountiful salmon runs.

(Trevor Popoff/T•)

When the area was settled by Europeans, the potential of the space was noted from “day one,” according to Ruskin. There were no permanent Wendat settlements (not that that would have stopped the Europeans anyway) and the natural fortification of the valley provided protection from the Americans during the War of 1812.

Quickly, citizens began making use of their natural neighbour. The river provided transportation, the lush forests provided copious amounts of wood to build the bones of what would eventually become a world-class metropolis, and the running water of the Don River created opportunity for industry.

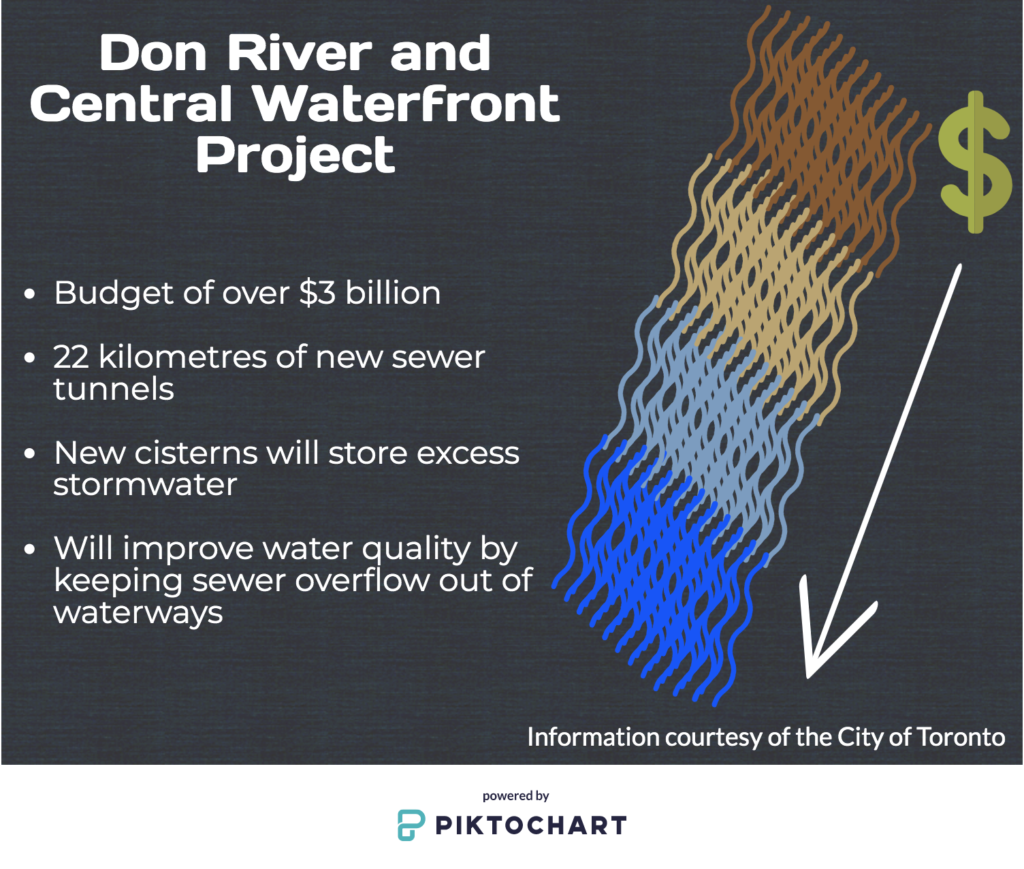

But, the growing populous was producing a lot of waste, and the sprouting settlement had no sewage system. So, those wearing the civic pants at the time concocted an idea: bury the Don’s tributaries and turn them into sewers. These waterways, still interred in Toronto mud, are what Ruskin refers to as “lost rivers.” Ruskin offers tours to where metal grates allow glimpses into this hidden world.

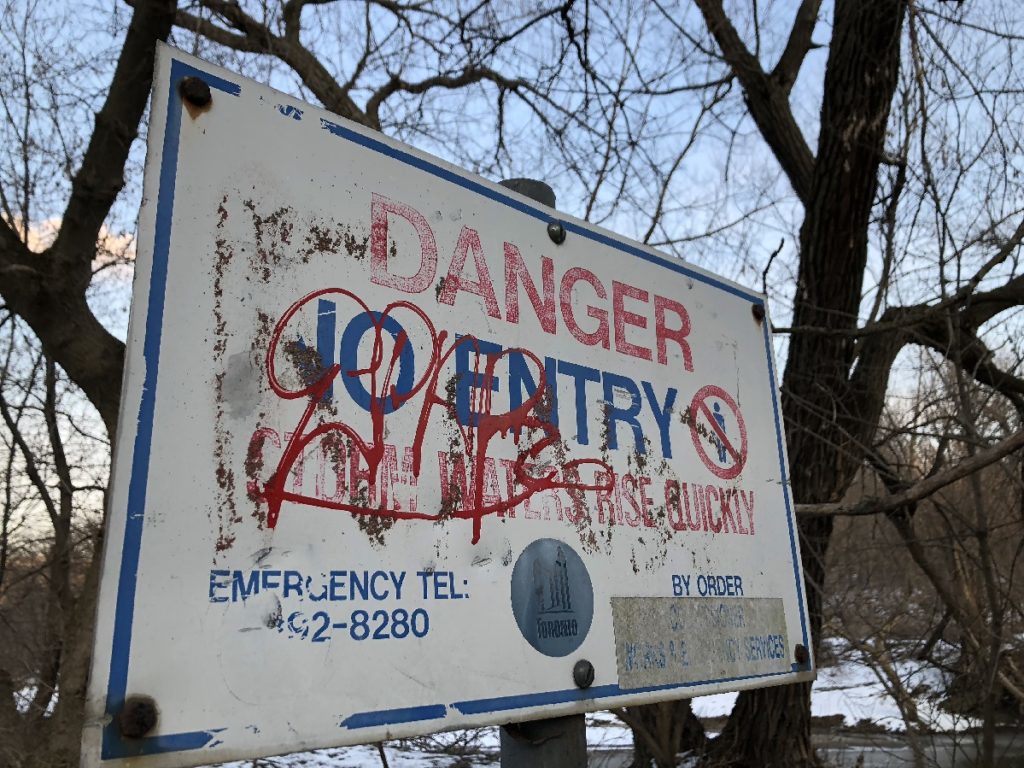

The Don River’s waters made it possible for Toronto to become a metropolis, but in the era of climate change, those same waters threaten to bring the city to its knees. A major flood should happen once every 500 years, says Ruskin. Three have happened in the past century. Ruskin believes that the time for change is now. “If you wait for governments to take action, the opportunity will pass,” he says. “If we don’t revitalize our ravines, we’ll get choked out.”

The present

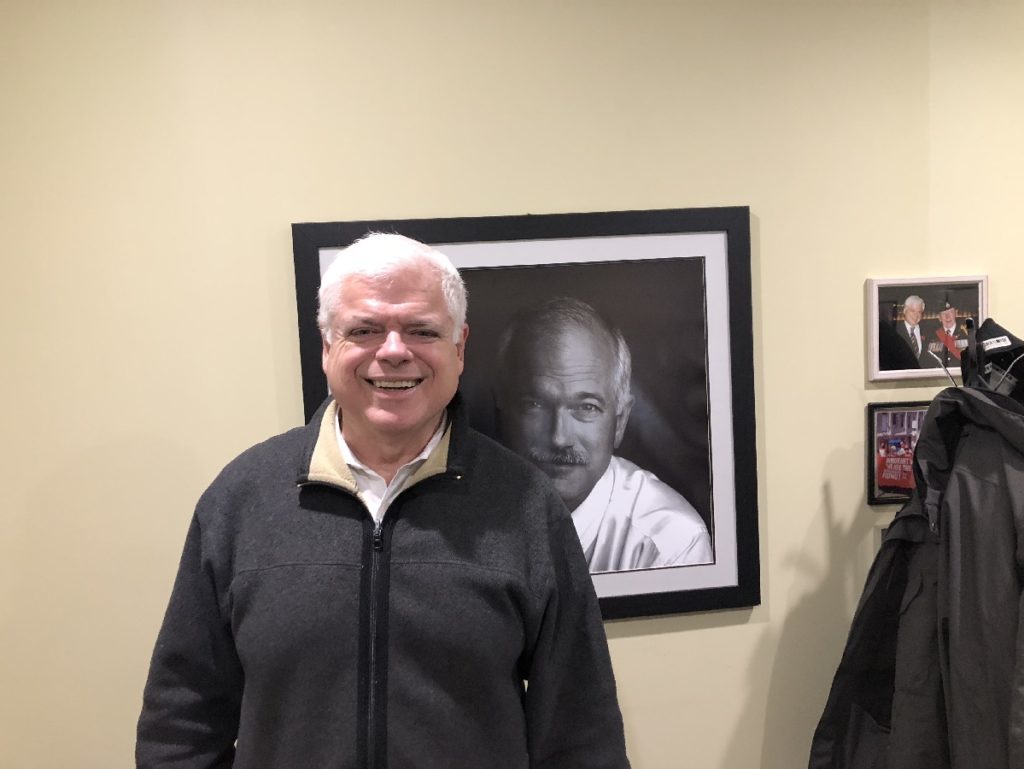

Brent Raymond reclines in DTAH’s Yorkville office, espresso in hand. A wall of windows allows him a panoramic view of the Don Valley. Such are the luxuries afforded to one of the top architects in Toronto. Instrumental in the Lower Don Trail Accessibility, Environment and Art Master Plan, Raymond has shaped the valley’s present era.

As he stares out the window at a thicket of winter-stricken trees, he begins to ponder the space he works in. “[The Don Valley’s] certainly unique,” Raymond says, “not only in Toronto, but perhaps in North America, if not the world, as a massive natural setting within a very dense urban environment.”

Since getting started on the plan in 2013, Raymond has adapted trails for multiuse, built a bridge across the river at Pottery Road to curb a jaywalking (or jaycycling) epidemic, and added wheelchair-accessible ramps.

Improved accessibility was emphasized by the city when DTAH was contracted to overhaul the Don’s trail system, but the firm has faced challenges working in a space with such a unique past. “We find things like informal dump sites every time we dig,” says Raymond. “That slows us down.”

Another part of the equation for Raymond and his team is reconciliation. The firm consulted with Indigenous peoples and are trying to massage in some of their requests. “They want to see camping in the valley for youth groups, be able to plant food, go fishing, things like that.”

When it comes to park design on the banks of a river, flooding is certainly part of the discussion. DTAH was also involved in the planning of the Evergreen Brickworks, and planned for the facility to withstand flooding, but not at this rate. “What was once a hundred-year storm is happening every 10 years,” says Raymond, “but not many cities in the world have a natural space like this. There needs to be more engagement from people. The more people love it, the more people will take care of it.”

The future

According to the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, the Don River’s watershed is “one of the most urbanized in Canada.” About 1.4 million people live along the Don’s 38 kilometres, which stretch from Newmarket to Lake Ontario. About 104,000 of those people live in Peter Tabuns’ provincial riding of Toronto-Danforth. MPP of the locale since 2006, Tabuns has been around the block when it comes to provincial politics. So, when he’s thrown off by a piece of legislature, something’s up.

Recently, Doug Ford’s government rewrote the Environmental Assessment Act, an edict with which Tabuns is still grappling. “Conservatives all have the same plan when it comes to the environment, and it usually involves a sledgehammer.”

The alterations to the document may allow the province to overwrite any bill the City of Toronto could pass relating to the environment. Tabuns believes the rewrite comes in anticipation of the Ontario Line, Ford’s proposed Toronto transit solution.

Tabuns has already identified one problem with the Ontario Line. The tracks are slated to cut through protected lands in the Don Valley. A new bridge would be necessary, meaning a construction project that would disrupt the environment and Tabuns’ constituents alike.

Constituents who, Tabuns says, are already upset. Many homeowners near the Don have told him that insurance companies are refusing to give their homes flood protection.

“All of the talk is about floods in the valley, but I believe we could see droughts and fires too,” said Tabuns. “There is no set point with climate change. You’re always chasing an invisible mark.”

And that’s what the Don Valley sometimes feels like: invisible. To the thousands that pass through it daily, it must feel like a constant. But it cannot be taken for granted. The Don Valley is not a static space. It is a living, breathing entity, where every present second is a product of its ancient past, and every future action will be influenced by the doings of those who came before.