By Rhea Singh

Twelve years ago, Mafalda Oliveira was just a yoga teacher.

At 20 years old, Oliveira spent her lessons teaching students warrior poses, transitioning from basics to intermediate yoga. That all changed when a new student walked in and, to Oliveira’s surprise, she was pregnant. Oliveira didn’t know how to cater to her student or how to teach her yoga while she was pregnant. But those barriers didn’t stop her from trying.

Oliveira began to take prenatal teacher training as a way to break down the barrier between her student and her yoga teaching. When the woman was reaching closer to her due date, she invited Oliveira to the birth to help with breathing exercises and calming her down.

“One of the nurses asked me if I was her birth doula and at the time I didn’t know what that was. But because I loved the experience so much I went and did research and became a birth doula after that,” says Oliveira.

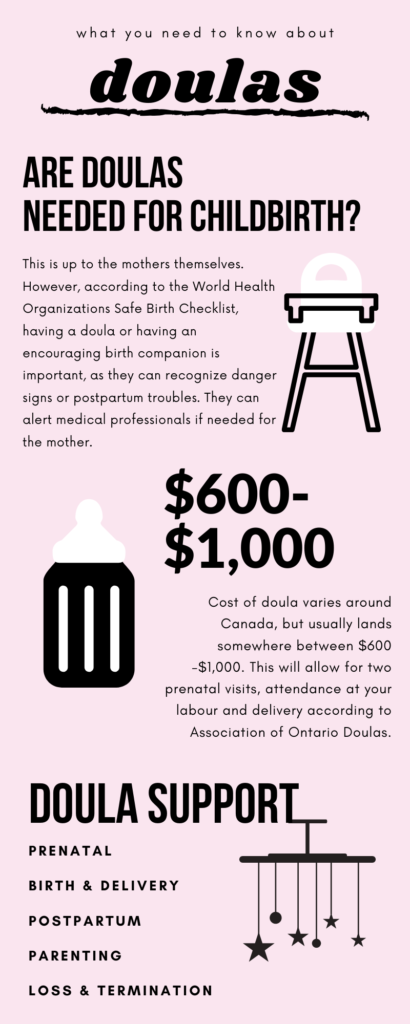

The word “doula” would soon become part of Oliveira’s everyday life. Doulas are certified professionals trained in childbirth, prenatal and postnatal care, or termination. The journeys they take with their clients aren’t medical, but emotional, physical and educational.

When Oliveria officially began her doula training in 2016, she got her start at community centres where she acted as a translator and doula for families from Brazil and Portugal. Oliveira would explain and guide them through the importance of vaginal births, as many leaned towards having C-sections instead.

Most women within the Portugese community prefer C-sections to natural births, says Oliveira. In 2011, a study published by Rev Saude Publica stated that among the Brazilian women who were monitored, overall C-section rates reached 45 per cent and 81 per cent among private patients.

Now at 31, Oliveira runs her own doula agency, Mama Doula, alongside friend and co-founder Melissa ‘Mel’ Rafaela. Mama Doula offers services such as help with infertility, pregnancy labour/delivery and postpartum care. It also has workshops for care and support during the birthing journey. Including Rafaela and Oliveira, Mama Doula has a team of eight trained doulas, that cater to services from birth to postpartum care. The agency is the brainchild of two women who saw a lack of support when it came to birthing in the Portugese community in Toronto. And, as mothers, they saw it as a support system for each other.

“The first time we met we really connected. We were both mothers and at the time I didn’t really know how to work by myself, to have a child and be on call 24/7,” says Oliveira, who met Rafaela through the Portugese community in Toronto.

Being on call 24/7 comes with the job, says Rafael. Her day does not begin with an alarm but with a call – from mothers, partners of mothers or potential mothers. “Sometimes you have 48 hours of no sleep, and that’s very intense,” she says. “I could be heading to bed, or just putting my kids to bed, and then I get a call.”

A 2010 study published by the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada found that reasons for discontinuing doula practices were linked to on-call requirements 50 per cent of the time and difficulty in balancing family demands and obligations at 43 per cent. However, the study did find that 89.6 per cent of participants said they chose the job in order to support women in childbirth and 42 per cent linked their interest in the job to their own birthing experience with a doula.

Every week is completely different. Sometimes there are no calls. Then suddenly there’s a wave, a baby wave. But this isn’t a burden for Rafaela – these calls are what she is passionate about and have become part of her job.

“You could have two birthings in a row, and even once you are done with those birthings, you still have prenatal and postnatal appointments with those clients,” says Rafael.

Similarly for doula Gillian Cullen, 20 to 30 hours of work a week became the standard when caring for postpartum clients. Since her first doula training class in 2014, she has had over 150 clients. Navigating on-call life is tough and can mean missing birthday parties, holidays and special events, she says.

“I knew that just surviving on birth fees alone, you would have to take six to seven births a month. That’s not humanly possible, but I did that for a while,” says Cullen.

Even with the high demand, the profession provides memorable “magical moments,” she says, especially that moment when a mother and family connect with their baby. Cullen knew the sleepless nights and 2 a.m. calls from mothers were worth it after she attended her first birth.

Now at 38, Cullen is executive director of BirthMark Support, a registered charity founded in 2018 to provide doula services to people from marginalized communities. Much like Mama Doula, BirthMark’s services include termination and loss doulas, labour and birth doulas, and postpartum. Cullen started BirthMark Support after she saw a gap when it came to serving mothers in marginalized communities.

Growing up in Rexdale, Cullen had become a mother at 19 and had three daughters by the time she was 23. As a survivor of domestic violence and a young mother, she felt alone and isolated. She also watched a lot of her friends and people in her community navigate tough situations in their underserved area. Cullen understood the importance of having the right person to guide you through an important stage in a mother’s life.

“A lot of the time, when we look at the way this country was built, having a white middle-aged woman (doula) is not going to be the safest thing for a lot of our clients.” says Cullen.

Trauma for mothers can come in different forms and waves. A study published by Statistics Canada in June 2019 found 23 per cent of mothers who had recently given birth reported consistent links to postpartum depression or anxiety disorder. The study also found 67 per cent of mothers opened up about their mental health to family, friends or health professionals.

During Oliveira’s second pregnancy, she experienced severe stress, linked to problems with her husband and it made her birthing experience much harder than anticipated. But having a doula, a person in whom she found support, made the experience much smoother.

Having two birthing experiences with a doula made Oliveira realize that the stress was much deeper and that, in theory, she was hiding something from herself. “It made me a better doula when it comes to giving as much emotional support as I can, as a woman and as a human being,” she says.

Rafaela likes to say it’s more psychological than physical, notes Oliveira. If the mother doesn’t trust the people around her, the birth becomes much harder. There is a deeper meaning to labour and motherhood

Becoming a mother isn’t for everyone, she says, and the stigma against women who choose not to have children is slowly fading. That’s mainly because people are starting an open conversation on how motherhood shouldn’t be always expected of a woman.

“We are at the cusp of this change in society where women are starting to really be able to use their voice and have strength, and the more we talk about it, the more we keep the conversation alive,” says Cullen.