By Gary-Joseph Panganiban

Sorting through donated objects is the last thing Zinash Mekkonen envisioned herself doing when she came to Toronto from Ethiopia a year a half ago. She majored in chemistry at Addis Ababa University and was a flight attendant before arriving in Canada with her husband and children. She began working at St. John’s Thrift Store six months ago after seeing an online posting.

“The first week was a struggle,” says Zinash. “For one or two days, I would go home and cry. I felt depressed.”

She says the tasks related to the job were not the most labour intensive. It was the feeling she could do more that bothered her the most. But after some time and reflection, she says she realized that going through donations and pricing clothing were part of an inevitable transition period.

Tucked in between The Bartending School of Ontario and a Home Hardware on the busy and commercial Danforth Avenue, Zinash’s workplace is easy to miss. With plain lettering printed over a white backdrop, it is devoid of the vibrant colors of its neighboring businesses.

But there is something that makes St. John’s Thrift Store stand out that is not obvious to the casual observer.

The shop is an Employment Social Enterprise. An ESE is a business that provides “training and opportunities for people facing systemic barriers to entry into the mainstream labour market,” according to the Toronto Enterprise Fund, a United Way of Greater Toronto program that supports ESE businesses.

Depending on the business, the model seeks to train and employ newcomers, people with disabilities, individuals with criminal records, among others, with the hope of bridging them into the mainstream workforce, says Paul Chamberlain, a TEF manager.

According to TEF’s website, 3,641 individuals from 63 projects funded by TEF have gone through their partnered programs since inception. For the 2017-18 period, around $2.9 million in wages were paid to participants.

Paul says the real challenge for businesses is covering social costs—the added investment in training new hires who need more guidance. On average, these make-up 30% of total operating costs, though the figure depends on the types of business, explains Paul.

Incurring social costs, St. John’s Thrift Store appears handicapped against bigger businesses, especially when the Value Village one block down dwarfs the small store with a legion of cacophonous tills, aisles of clothes, and even parking behind it. But no tax, an overflowing appetite for bargain hunting and a different approach to customer service draw people through the door at St. John’s.

Co-manager Larissa Moffat, who spends her days behind the cash register, is wrapping a customer’s purchase—three tiny ceramic houses. A compliment on the woman’s choice in home decor sparks an exchange of thoughts on clothes and the community.

Larissa, whose short gold locks brush over her green corduroy blazer, says that some simply visit the store for companionship.

“We have one lady whose son passed away,” says Larissa. “She just kept coming in here just because she felt it was comforting and a safe place for her to be while she was mourning.”

Tops and vests hang by the front of the store on Tuesday, March 3, 2020. (Gary-Joseph Panganiban/T•)

Bracelets and necklaces are displayed on a counter on Tuesday, March 3, 2020. (Gary-Joseph Panganiban/T•)

Pants line up against the west wall of St. John’s Thrift Store on Tuesday, March 3, 2020. (Gary-Joseph Panganiban/T•)

Larissa Moffat prepares to wrap a customer’s purchase on Tuesday, March 3, 2020. (Gary-Joseph Panganiban/T•)

Larissa Moffat stands behind the counter of St. John’s Thrift Store on Tuesday, March 3, 2020. (Gary-Joseph Panganiban/T•)

This warm environment is what helped Zinash transition through her difficult start.

“[The team] made it easier for me,” she says, perched on a metal stool with her fingers clasped. “They have respect. They are really nice, I love them […] they always let me know I can stay and if I have a problem, they help me solve it.”

The thrift shop is run by the St. John the Compassionate Mission, an orthodox church located on Broadview Avenue near Queen Street East, which also runs another ESE called St. John’s Bakery.

The religious leader of the church, Father Nicolaie Atitienei, whose broad shoulders and towering stature are emphasized by his dark baggy cassock (a Christian Orthodox vestment), explains that the mission mainly offers meals and counselling to the homeless. His words are hushed, but he punctuates every sentence with a smile.

“It’s a simple place and we do simple things,” he says. ”We pray, and then we work on people and we sit with them.”

Father Nicolaie says they also offer vouchers, redeemable at their thrift store. He explains that it allows the homeless to choose their own clothes instead of just receiving them.

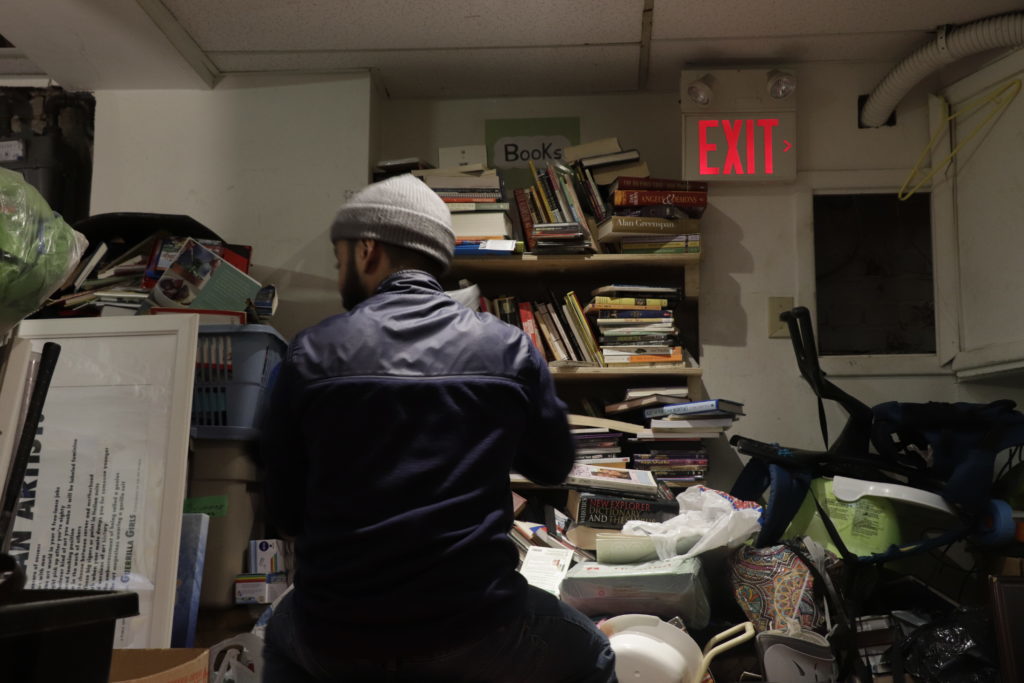

A sign that reads “No customers allowed – Employees only” leads to the basement of the thrift store—the heart of the business. Down the carpeted red stairs, clothes-filled bags and boxes containing household items dominate the room. On horizontal poles elevated near ceiling level, hangers, on which more hangers dangle, overwhelm the unsuspecting eye.

Matthew Sanchez, the other co-manager at St. John’s Thrift Store who mainly oversees basement operations, assures there is a system to this apparent chaos.

“We have a three-step process,” he explains.

The first step is inspecting. Employees and volunteers retrieve the new donations and check for any damage. Anything judged unsellable at the store is re-bagged and picked up by a company to be repurposed elsewhere.

Next, items are sorted and priced. Some workers test the electronics. Others tag and hang clothes. All search for damages or stains.

The final step is bringing the items upstairs, where the salespeople like Larissa do one last verification before putting them on the racks or shelves.

As he sorts through the latest book donations, Matthew explains how the small team can sort 30 large plastic bags worth of items. While scanning the pages of a book in near-mint condition, his fingers on the other hand disappear through his dark brown beard. He analyzes the front and back cover, and googles the book’s title before stacking it on a pile of others in similar condition.

Matthew Sanchez sorts through donated books in the basement of St. John’s Thrift Store on Wednesday, March 4, 2020. (Gary-Joseph Panganiban/T•)

Matthew Sanchez inspects the condition of the donations on Wednesday, March 4, 2020. (Gary-Joseph Panganiban/T•)

Books deemed adequate are placed in designated boxes on Wednesday, March 4, 2020. (Gary-Joseph Panganiban/T•)

“When we have volunteers, they are always helpful,” says Matthew. “Larissa, Zinash and I are a bit more experienced; we know how to handle clothing, but sometimes it can get quite stressful when it comes down to just us three.”

Despite her initial struggles with adjusting to the new job, Zinash now finds purpose in what she does.

Crowned by a white knitted headband, her forehead shines beneath the dimmed lighting as her stare wanders. The plastic bags rustle and the hangers clink under her touch as she surveys her next tasks.

“When you sort [items], you will think about other people,” says Zinash. “Someone will think ‘this is almost gone,’ but you feel someone might use it.”

Her employment contract at the ESE ends in August. Although she hopes to study once her time at St. John’s is over, she does not see herself closing that chapter.

“I don’t think I would have left them totally,” says Zinash.

“Anytime there would be a volunteer position, I would like to help them.”