By Anna Maria Moubayed

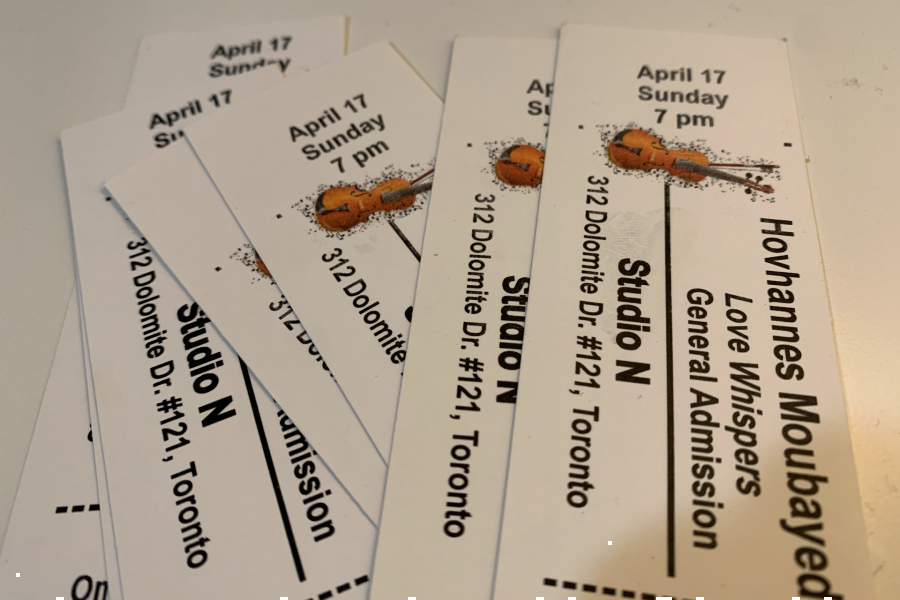

A few months after moving to Toronto, I help my dad, Wanes Moubayed, prepare a list of songs to be performed at his solo violin concert at Studio N. Our family was among 25,000 people who immigrated from Syria to Canada between 2015 and 2016. This will be his debut concert in the new city. Emails are sent, posters are freshly printed, all featuring his name and photo, along with the concert’s theme: “Love Whispers.”

Two weeks before the concert, the manager of the event tells my father that a man wants to speak to him. Shortly after, as Moubayed makes his way home from work at a music school, he receives the call. Confused by the unusual situation, bothered by the crowded TTC bus, yet curious, Moubayed answers the call from this unfamiliar person. On the phone is a man ready to deliver some life-changing news — both for himself, as well as Moubayed.

A few days earlier, architect Harry Mardirosian was sitting at his desk at his office, looking through his emails about a project he’s working on, when he noticed an email announcing a solo violin concert. He is interested in the performer — more specifically his name.

Mardirosian recalls “Wanes Moubayed” typed in capital letters in his old Syrian passport. Syrian passports include parents’ names, and “Wanes Moubayed” is printed on the “father’s name” line.

The name on the poster is the same as his father’s.

Mardirosian gives Moubayed a call. He can think of many different reactions the violinist might have with every ringing sound, until a “hello” interrupts his thoughts and greets him from the other side.

This phone call marks the beginning of an instance of reunification of lost family connections through a diasporic life. It is a story broken up into puzzle pieces due to wars, economic crises and extraordinary circumstances, scattered across the globe for decades.

Aleppo, 1952: one January morning Harry’s father Wanes Moubayed, a handyman, leaves home on an emergency call to fix a broken pipe. On his way, a roadblock prevents him from crossing Sulaymaniyah street, one of the busiest streets in the area. There is a blockage for a funeral procession of a high ranking army personnel. People passing by stop to watch the string of military vehicles while workers peep out of their stores. Regular business halts for a few minutes. Moubayed asks the officer to be allowed to cross. The officer refuses several times. Somehow, eventually, Moubayed persuades the officer to let him cross to his final destiny. As he crosses the street, two military vehicles hit him. The news of the disaster reaches the family by noon.

Mardirosian is only four months old. His mother, Parantzeme, becomes the family’s sole bread winner. She works as a nanny. Later, she invests in a sewing machine to take up customers’ made-to-measure orders. She also works in Hotel Baron as a maid. Living through the agony, she would rarely speak of her husband.

“I hardly used to see her. She would leave early in the mornings for work and come back late in the evenings,” said Mardirosian.

Relations with the paternal side of the family are cut off after Harry’s father’s death.

A few years pass. Parantzeme hears about a program at the Mkhitarian School in Aleppo where boys are sent to Italy to train for Catholic priesthood. Parantzeme deeply values education, and worries about taking care of the boy’s schooling, along with everyday needs as a single mother.

So, at nine years old, Mardirosian leaves Aleppo to San Lazzaro degli Armeni. Finding information about his father becomes even harder.

In his luggage, Parantzeme manages to fit a thick album of family photographs, often taken at Mashtal Park. There is not a single photograph of him with his father.

“Photographs are important in the larger context of history,” said Arto Vaun, the executive director of ProjectSave, a digital photography archive. “They show what was happening at a certain point in time through personal and detailed narratives because it comes directly from the people of the time.”

“Preserving family history is a problem because preserving families is a problem,” said Vaun.

Physical separation of family members, along with lack of memories of these family members creates a great disconnect. When things are not archived or documented, they can get lost through generations, he said.

As Mardirosian grows into his teenage years, he realises the monastic lifestyle is not his calling.

After six years in Italy, Mardirosian leaves Saint Lazarus. At this time, it was dangerous to return to Syria, as the Six-day War was at its peak. Mardirosian goes to Beirut, while his mother and grandmother stay in Aleppo. It takes him and his family one year to earn the immigration visa for Canada. After years of separations, the Mardirossian family is reunited in Toronto at the end of 1968, finally celebrating the New Year together. Soon, Mardirosian leaves his new home for architectural studies at University of Michigan in 1970 and the University of British Columbia in Vancouver until 1977.

Looking for family from his paternal side was a dormant thought on Mardirosian’s mind, and life’s daily hustle and bustle kept it as is.

One day, his son asked what happens if he dates a girl and they decide to marry, then later find out they are blood cousins.

“I was taken by surprise,” said Mardirosian. “I had no swift answer to this valid question.”

After Mardirosian’s call, Moubayed tries to understand where on the family tree the Mardirosian branch would fit. Because of the sudden move, he barely has any photographs or documents of himself, let alone his extended family.

In the summer of 2012, my family and I decide to go on a two-week vacation to Armenia. A few hours into the trip, the conflict in Syria reaches the city of Aleppo. As the situation got worse, all travel to and from the city was cancelled and deemed dangerous. We slowly came to terms with the fact that we’re stuck in Armenia. Then, the realisation dawns upon us that we have nothing but a “two-weeks-trip” worth of summer clothes and a life left behind.

One of the only things I have from Aleppo is a box of unopened coloured pencils. My love for arts and crafts had led me to pack it in with my clothes. To this day they are unopened — a sole reminder of home.

One of the only things Wanes has from Aleppo is his violin. His lifelong dream of studying music with some of the most skilled musicians in Armenia had led him to take the instrument along with him.

“It’s a big challenge to pick and choose what you want to take with you and preserve. It’s something that people who move due to extraordinary circumstances face,” said Cassandra Tavukciyan, specialist of digital collections management at Canadian Museum of History.

After almost four years of processing immigration papers, we move to Toronto in 2016.

After several conversations with extended family, rediscovered journals and calls back and forth with his parents, Moubayed finds the missing piece of the puzzle. If Harry’s mother’s name is Parantzeme, then the puzzle is complete: they are cousins.

On April 17, 2016, Mardirosian and his wife enter the concert hall, anxious and teary-eyed. Standing at the door with my mom, we check their tickets and greet them, unaware of the significance of the moment. They are some of the earliest arrivals.

“He thought about it for days, it was always on the back of his mind,” said Mardirosian’s wife, Edith. “If it weren’t a match, the disappointment would have been incredibly deep.”

There are about a dozen people scattered across the hall, looking through the brochure in dim lighting, speaking quietly. Mardirosian asks my mom if he can meet the artist. She points to Moubayed, her husband, standing in the distance in a black suit and a bowtie.

I watch from a distance as they meet for the first time.

Mardirosian approaches Moubayed and introduces himself as the telephone caller. Moubayed asks the critical question.

“What is your mother’s name?”

They are cousins.

“I was about to go on stage to perform, but that’s something I’m used to. This was new. It had never happened to me before. There was a mix of new emotions” said Moubayed. “I had to focus on the concert, but I was excited to properly meet my long-lost cousin afterwards.”

Towards the end of the event, Moubayed steps toward the microphone for his concluding remarks about how music impacts humanity.

Music connects, brings understanding, harmony and love among people, he says. With music, there are no borders separating people, no conflicts. “It is through the power of music that I discovered my cousin in the audience today, to whom I dedicate my next piece.”

It is an unbelievably ecstatic moment for Mardirosian. He cannot grasp the truth of the moment.

“The moment is short lived,” he writes in his journal.

Applause persists for a couple of minutes. Gradually the lights come on. The attendees start to make their way out, slowly deserting the concert hall, leaving behind two islands of families to bridge the gap between them.