By Amelia Singh

“In Tunisia, we don’t do that. You take care of your parent like they did for you until they are gone. But that is what it feels like, like I am sticking her in a retirement home to die on her own one day.”

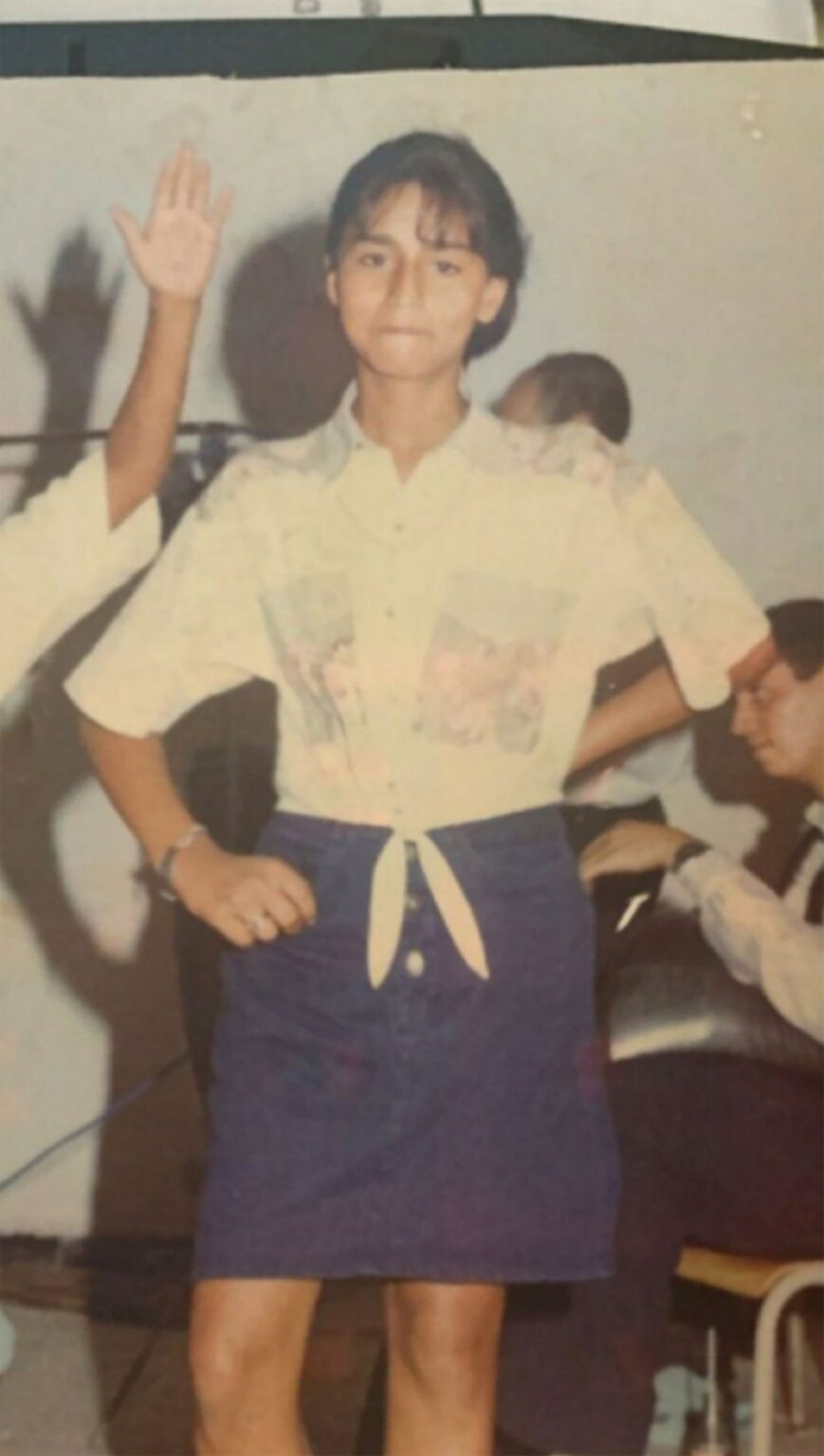

Asma J.

When Asma J. woke up on Oct. 4th last year, she expected to go about her normal routine: wake up the kids, make breakfast, and complete her daily check-in with her mother, Omi, living in Tunisia. With the kettle whistling on the stove, her five-year-old muttering to himself as he brushed his teeth, and finally a moment to herself, she noticed her usual notifications hadn’t appeared on her phone. She double-checked the time, thinking by some bizarre chance she had simply imagined it was morning. Awaiting her, like any other day, should’ve been a WhatsApp message from her 68-year-old mother, but the only thing that greeted her eyes after opening the messaging app was a daunting loading symbol and no message. Panic began to set in.

Like millions of other immigrants using WhatsApp to communicate with their loved ones back home, Asma found out after a few minutes of investigating that alongside Facebook and Instagram, WhatsApp had suffered an outage, with no estimate for when it would be back up and running. Despite only being down for what turned out to be approximately seven hours, the incident left a hushed fear in those who use WhatsApp as an essential tool for staying in contact with their families overseas, whether just for simple communication or for ensuring their safety when living in danger.

Thirty-four years before that dreadful morning, Asma faced a different challenge—immigrating to a new country. At 10-years-old, she was promised that fleeing her humid and sandy home of Hammamet, Tunisia, with her father was for the best; that life would be better in North America. Whether that’s true or not, the 44-year-old front-end cashier and mother of two candidly admits she will never know. One fact she does know to be true is that life would be better with her mother by her side.

“I’ve seen her maybe three times since I left, but it is still hard, you know?” said Asma, her son Miko’s indistinguishable, colourful crayon scribbles on the wall behind her a haunting reminder of all the milestones her mother has missed. “Her cancer has relapsed a few times, so I am not able to take care of her, but with WhatsApp, I can text and call and make sure she understands everything and is managing okay.”

Not being able to take care of her mother when she needs it the most, Asma can’t help but feel guilty. “I’ve seen people over here, they announce proudly that they stick their mothers or fathers in homes, for other people to do the work,” said Asma, full of disbelief for the habits of her non-immigrant colleagues. “In Tunisia, we don’t do that. You take care of your parent like they did for you until they are gone. But that is what it feels like, like I am sticking her in a retirement home to die on her own one day.”

For individuals like Asma’s mother, who live in developing countries, the words “WhatsApp” and “Internet” can be synonymous. Released in 2009, the messaging service has become their favoured platform for local and international communication for one reason: it’s free and not dependent on mobile data costs around the world. According to a study done by Cable.co.uk, an organisation that provides free and independent advice on buying cellular and internet services, the costs for different cellular services outside of North America and Europe can be astoundingly low, like in India where 1GB of data costs a mere 87 cents. Conversely, in other countries, the same 1GB can rack up to a whopping $62. With the incredibly low cost of data in many of these countries, most citizens opt to pay for cheap unlimited 4G data plans and use WhatsApp as their main method of communication, as opposed to a regular cell phone plan.

While the low cost of data may seem alluring, it, unfortunately, means when WhatsApp goes down, not everyone has the privilege of switching over to a cell phone plan or landline. For some people, it could be the difference between life or death.

Krystal Sukhu says her grandmother, who lives on her own in Guyana, is one of those people. Using a local group chat to monitor contact tracing for COVID-19, her grandmother knows what parts of town to avoid so she can stay safe. “In her old age, catching COVID could mean the end,” said Krystal. “In Guyana, vaccines were hard to come by for a while, and still are, so her life really rests in the hands of that WhatsApp chat.”

This has also become reality in Ukraine, where the line between life and death has thinned and millions are seeking protection from the current Russian invasion. In early March, the State Emergency Service of Ukraine launched a WhatsApp information helpline that allows users to efficiently access reliable updates and other critical tips or news that could influence the course of their lives forever. WhatsApp also provides extra peace of mind to those fleeing Ukraine and other war-ridden countries with its end-to-end encryption, meaning not even the app’s creators can see what messages are being sent, let alone any authoritarian governments that might be looking over the shoulders of innocent refugees for intel.

These stressful situations aren’t any easier on the people supporting from the sidelines. Struggling alongside Asma is her 19-year-old daughter Leila, who tries her hardest to help her mother between attending college and babysitting her younger brother. Raised by a single mom, Leila recalls moving around the continent frequently, starting in sunny California, with pit stops in Edmonton and Montreal, before settling down in suburban Toronto. Throughout all that, their relationship was never perfect, but for better or worse, they always had each other’s backs when things got hard. Unfortunately, the thousands of kilometres between Tunisia and home means her grandmother lacks the same support.

“I see our relationship and how close we are, and I cherish that so, so much. It hurts me to watch her and know that she’s missing that with her own mother,” said Leila, struggling to find the words to express her sympathy for her mother’s sorrow.

As hard as it has been, Leila professes WhatsApp is a blessing for her too. Having no connection to her extended family, WhatsApp has been crucial for her in forging some with not only relatives unknown, but with her culture. In fact, her mother’s use of WhatsApp is so commonplace, that Asma forgets sometimes to tell her she has passed her number on to another relative who wants to chat. Leila reminiscences about receiving a call once from a number, area code unfamiliar to her, and ignoring it, only to find out 10 missed calls later, that it was from an uncle living on the other side of the world whom she’d never met, wishing only to make sure she was staying safe on the long commute to school that her mother had mentioned oh-so briefly in her calls to him.

No matter what country or time zone you’re in, there is someone like Asma J. refreshing WhatsApp, looking for a message, a check-in from their loved one saying they’re safe, allowing them to let go of the breath they didn’t know they were holding. Asma knows the events of Oct. 4th may have been a one-time occurrence, but if it’s revealed anything, it’s that for her vulnerable, cancer-struck mother and millions like her, WhatsApp could one day be the very thing that saves their lives.