By Annemarie Cutruzzola

As Maria Rozysnka circles the small kitchen of The Depanneur, the flowered apron tied at her waist flutters around her. She cracks eggs with speed and precision, her hands moving back and forth to separate the yolks from the whites. Her phone lies in a ceramic bowl, amplifying traditional Polish music throughout the room. Her guests begin to arrive, stepping off College Street and into the warmth of the cozy venue, a former convenience store turned into a hub for culinary innovation. Rozynska slows down her preparations to greet each of her guests. Then she’s back behind the counter, ensuring the egg yolk mixture is whisked to her satisfaction.

When she was a child, Rozynska’s family left Poland to escape communism. Even in those dark times, food was a way of keeping her heritage alive. She grew up watching her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother make traditional Polish dishes. The lively and welcoming environment, fueled by music and vodka, also stands out in her memories.

“Polish food is more than just food,” she says. “It’s cuisine you could feel at home with.”

Rozynska wants to recreate this atmosphere for her students, but not just with Polish cuisine. She’s brought in chefs that specialize in a variety of cultures to teach hands-on classes for her cooking school, Just Be Cooking. Each class also features a communal meal and live traditional music.

“It’s a way of using all your senses to experience a culture. It’s not just a cooking class where you’re making something. You’re listening to the music and you’re eating what you’ve made,” she says.

Cooking hasn’t always been a passion for Rozynska. While she was completing her master’s degree in Dublin, Ireland, Rozynska was used to making microwave dinners for her meals. But one day she decided to tackle a dish she found on a recipe-a-month calendar.

“I nailed it,” she says. “Something in me like a light bulb went off.”

She started out teaching pierogi workshops in Toronto, which remain her most popular classes. As Rozysnska continued to work with many different chefs and musicians, she gradually incorporated the musical and multicultural elements that make Just Be Cooking what it is today.

“I quit my job about three years ago, to pursue this dream of bringing three of my passions together, which are cooking, singing and teaching,” says Rozynska.

Just Be Cooking is now her full-time job, along with raising a one-year-old and seven-year-old. She hosts one or two workshops every month with the help of a small team.

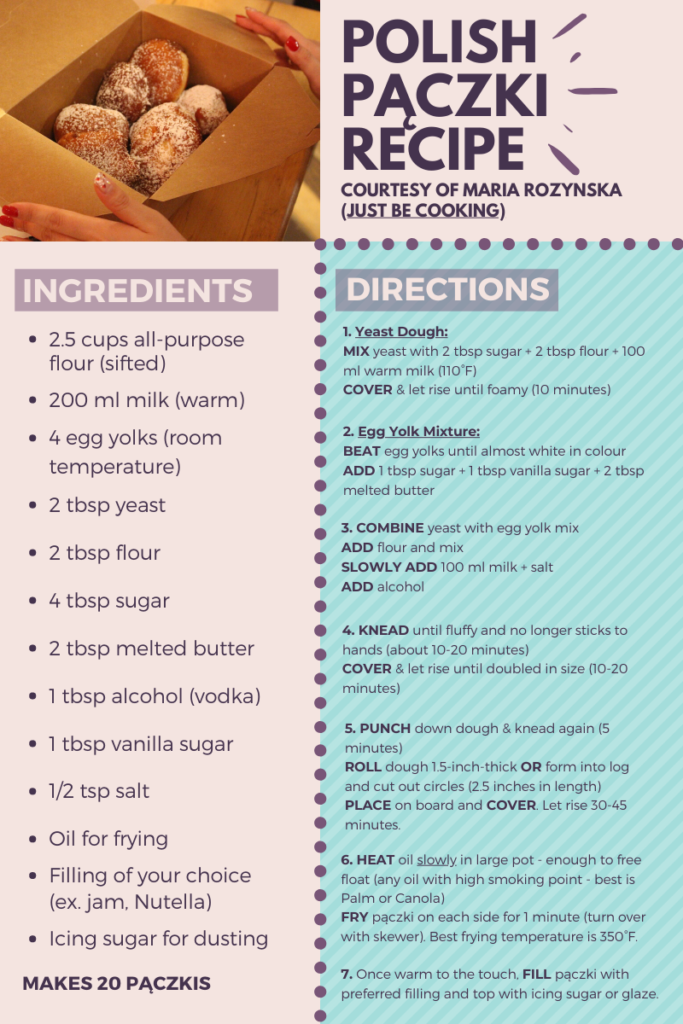

February’s workshop was themed around pączki (pronounced punch-key), a traditional Polish jelly doughnut. In Polish culture, pączkis are made at the beginning of Lent to use up ingredients like lard and sugar.A couple of hours into the class, the pączki dough has been made from scratch, kneaded for 20 minutes and left to rise. But Rozynska tells her students they “need to knead” for another five minutes. As their hands repeatedly dig into the soft pączki dough, they crane their necks towards Rozynska. She begins to tell the story of a traditional Polish song called “Hej Sokoly”, which translates to “Hey Falcons.”

The tune is about a Ukrainian soldier called a Cossack. As he’s going off to war, he looks up to the sky at the falcons. He’s jealous of the birds that can see the beauty of his country. He knows he never will because he won’t return alive.

“These songs were sung by women who were making pierogies communally like this, or pączki,” says Rozynska, still working the dough as she speaks. “They would sing songs about their fallen husbands, uncles, brothers, or sons who never came back.”

Rozynska sings “Hej Sokoly” while kneading her pączki dough. (Annemarie Cutruzzola/T•)

Rozynska shows her students the air pockets that appear inside the pączki dough after kneading it. (Annemarie Cutruzzola/T•)

When she starts to sing, the chatter among the group falls quiet. Everyone continues to knead. The intensity of Rozynska’s voice cuts through the silence in the room, punctuated by the occasional slapping of dough against the wooden counter. At the end of the song, her students erupt into applause before putting their hands back to work.

While they wait for the dough to rise, Rozynska reviews the pączki recipe with the group, trying to help them remember the quantities of each ingredient.

“2, 2, 2, 1, 4, 2, 1, 1- it’s like a phone number. The pączki hotline!” she says. “I like to teach like this. It sticks in your head.”

Having worked in the education sector for 20 years, Rozynska says that teaching comes naturally to her.

“When I teach, I don’t just teach how to cook. I teach the history behind it,” she says.

As Debbie Walsh takes her risen pączki dough out of the warm oven, Rozynska praises her work. “That’s exactly what you want. Doubled in size.”

Walsh works in IT for an investment firm by day, but her real passion is baking. Rozynska’s performance of “Hej Sokoly” was memorable for Walsh. “I really felt the emotion behind her song. That will stick with me,” she said.

Along with the personal connection that comes from taking a class, Walsh also appreciated the historical and cultural context. “I’m a fifth-generation Canadian. I’m not exposed to a lot of cultures,” says Walsh. “It expands my understanding of other cultures and other people’s plights, what they’ve been through to come to this country, and why the food is so important.”

As a refugee, this is something Rozynska is familiar with first-hand. She shared the story of her family’s escape from Poland with the class.

“We could tell no one of our plan,” she says. “We just walked out the door one morning.”

Her family would share and trade whatever food they could, during both the rationing in Poland and their time as refugees in southern Italy.

“During those bleak times, Polish cuisine was kept alive in our homes, or in this case, hotel rooms, as a symbol of our heritage and resilience,” says Rozynska.

This hospitality is an integral part of Polish culture. During Wigilia, a Polish Christmas celebration, an extra empty seat is placed at the table, ready to accommodate an unexpected guest.

Rozynska made two varieties of authentic Polish pierogies. (Annemarie Cutruzzola/T•)

For a side dish, Rozynska made a grated beet salad, a staple in Polish cuisine. (Annemarie Cutruzzola/T•)

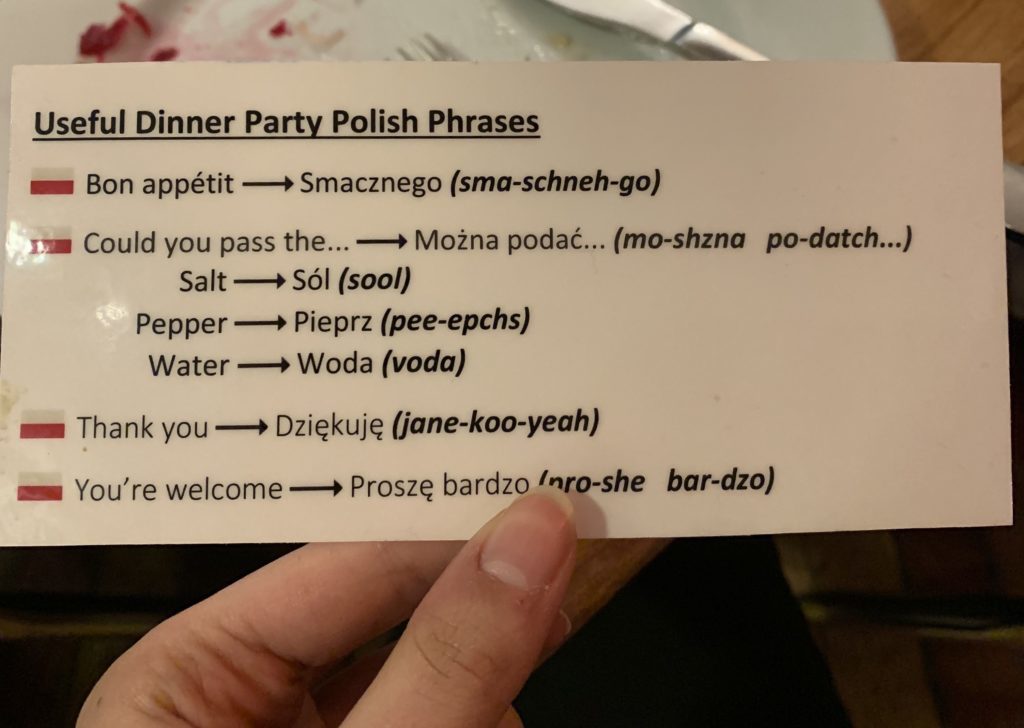

The students tried out some conversational Polish phrases over dinner. (Annemarie Cutruzzola/T•)

As the pączki dough is left to rise, the group sits down to eat their communal meal. Pierogies, mizeria (a Polish cucumber salad), and grated beet salad are passed around. The students came to the class in separate pairs, but now they’re all laughing and sharing stories.

I feel like I’m witnessing a family dinner. But Rozynska notices I’m sitting off to the side. Even though it’s nowhere near Christmas, she grabs an extra plate and pulls up a chair for me.

“There’s always room at the table,” she says.