By Edward Djan

Kiri Vadivelu is spending a snowy Friday afternoon organizing all the late payment notices he’s received from his building’s superintendent. It’s become a routine task for the Scarborough resident, who lives in Elmwell Towers, a 13-storey apartment building. The notices represent the many months of uncertainty.

Kiri spends most of his time as an outspoken community activist, speaking with his neighbours about the conditions tenants at 945 Midland Ave. are forced to live in. His activism usually starts as an elevator pitch, striking up conversations with other residents about tenants’ rights as they travel vertically through their building.

Kiri used to be afraid of confrontation. An introvert, he would try his best to stay away from any situation that involved him being the main subject. That changed once the pandemic began.

Kiri came to Canada as a refugee from Sri Lanka in 2001, escaping a bloody civil war that threatened minority Tamils like himself. He was eager to start a new life in Canada, having a goal of becoming a police officer. He studied criminology and justice at Ontario Tech University while living in a family friend’s basement.

After graduating university in 2011, the excitement of starting his new life quickly faded away after applying and being rejected from both the Toronto Police Service and the Ontario Provincial Police. Kiri decided to enroll in computer programming courses online, while also working as a security guard to gain law enforcement experience.

Kiri married his wife, Thushy Gunaseelan, the same year he graduated university and the couple moved into their current one-bedroom apartment the following year. After moving into their apartment, the couple’s financial situation became bad very quickly. The couple would soon learn their apartment needed a lot of work just to remain livable.

Kiri remembers the first day he stepped into his apartment like it was yesterday. It was a summer afternoon in the middle of June 2012. His building’s superintendent walked him and his wife through a one-bedroom apartment that had an echo. The lack of furniture in the unit made its flaws easy to see. Kiri walked over loose parquet floor tiles, passed walls with paint stripping off, and even saw broken interior locks.

The friendly demeanour of his superintendent, who assured the couple that all the problems in the unit would be fixed in time if they chose to move to the apartment, made him feel at ease. Having to pay only $1,040 for rent every month, along with the guarantee from the superintendent to fix all the problems in the unit, meant Kiri was eager to sign a lease to become one of the tenants at 945 Midland Ave.

He now scoffs at how naive he was.

Nine years later, the couple bundles up every winter inside their unit, feeling the cold winter breeze in a space that is supposed to shelter against it. They contacted their superintendent to complain about the problem, but Kiri claims the superintendent simply dismissed it.

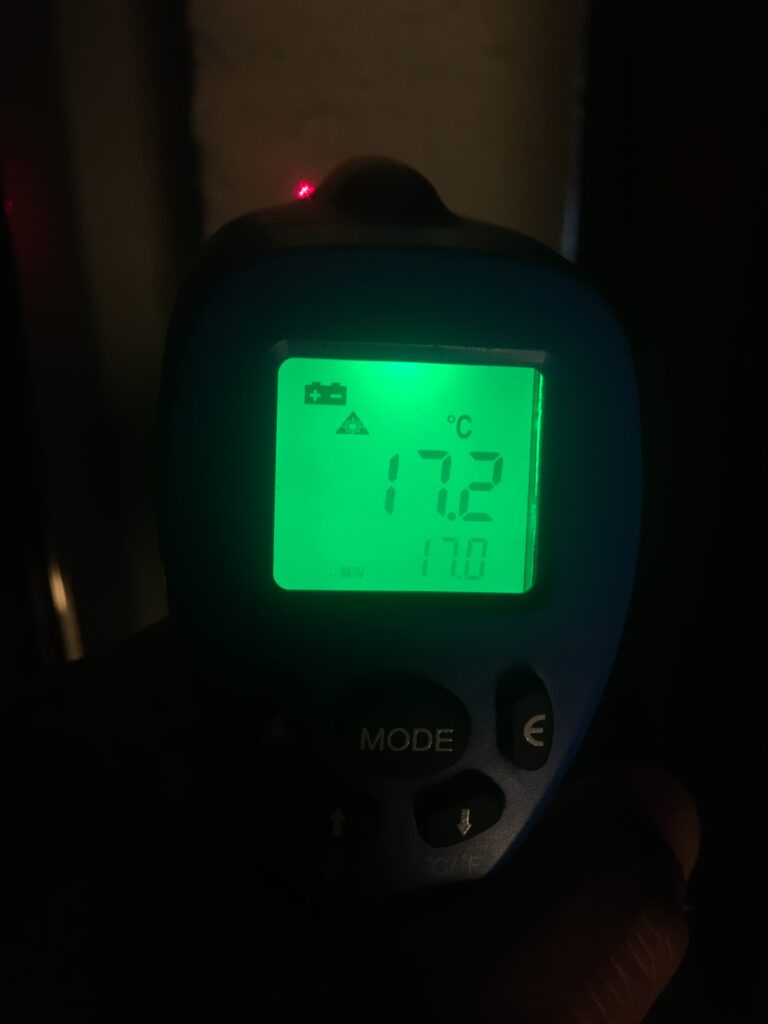

Becoming frustrated with his superintendent’s inaction, Kiri spent $235 on three heaters for his apartment. He also bought a thermometer to measure the temperature.

Even after spending money on heaters, Kiri and Thushy continue to live in the cold. He claims the last time he measured the temperature in his unit, his thermometer displayed a reading of 17.2 C, nearly four degrees lower than the City of Toronto’s minimum required temperature of 21 C landlords have to provide tenants.

A temperature reading of Kiri’s cold apartment unit on Feb. 19, 2021. (KIRI VADIVELU/T•)

Loose parquet flooring tiles in Kiri’s apartment on March 7, 2021. (KIRI VADIVELU/T•)

Despite the problems, they still paid their rent every month.

As Toronto descended into its first lockdown in March 2020, Kiri continued to work. He claims his employer forced employees to work in compact cars with a partner, barely having any room for physical distancing. He also says he was using his own personal protective equipment to do his job.

Kiri asked his employer for better working conditions, including the cleaning of vehicles, PPE, and mandated physical distancing. His employer terminated him for speaking up, Kiri claims.

He became one of the 355,300 people in Ontario who lost their jobs in 2020, representing the largest annual job loss in the province’s history according to the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario.

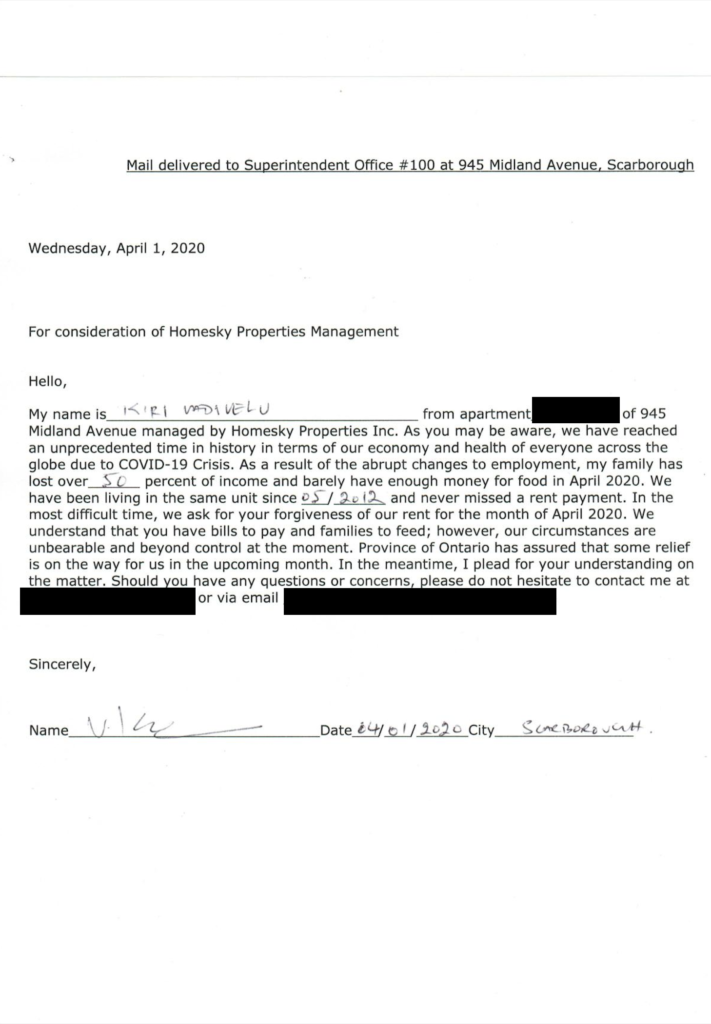

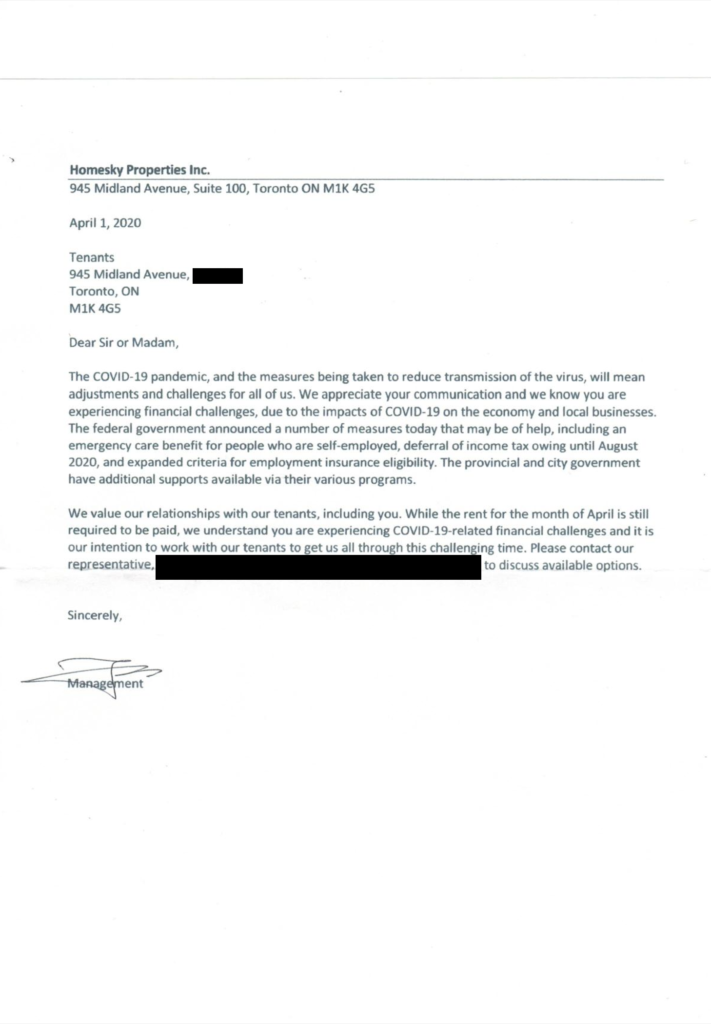

The couple was forced to rely on $2,000 a month from the federal government’s Canada Emergency Response Benefit, while also depending on the income made by the few shifts Thushy worked as a cashier at Walmart. Knowing that government assistance is not enough to pay his bills, Kiri sent a letter to his superintendent hoping to create a repayment plan once he found work.

Instead, he received a letter back demanding him to pay the rent and wait for additional government assistance to help him pay for his other necessities.

Then came April 8, 2020. Kiri was sitting in his unit when he heard a faint, quick knock on his front door. Kiri walked over to see who it was. Instead: There was a paper left on the doorstep.

It read: “This is a legal notice that could lead to you being evicted from your home.”

As he read the notice, the calm, shy demeanour he was known for was quickly replaced with confusion and anger. Reading through the notice, all he could think of was the amount of trouble he has gone through with his superintendent, whether it was with the heat in his apartment, his fridge not working, or the initial promises to fix the problems in his unit before he moved in.

Reaching the end of the notice, Kiri’s feelings became consolidated into one: betrayal. After paying his rent every month religiously despite all the issues in his unit, his landlord decided to start an eviction process against him.

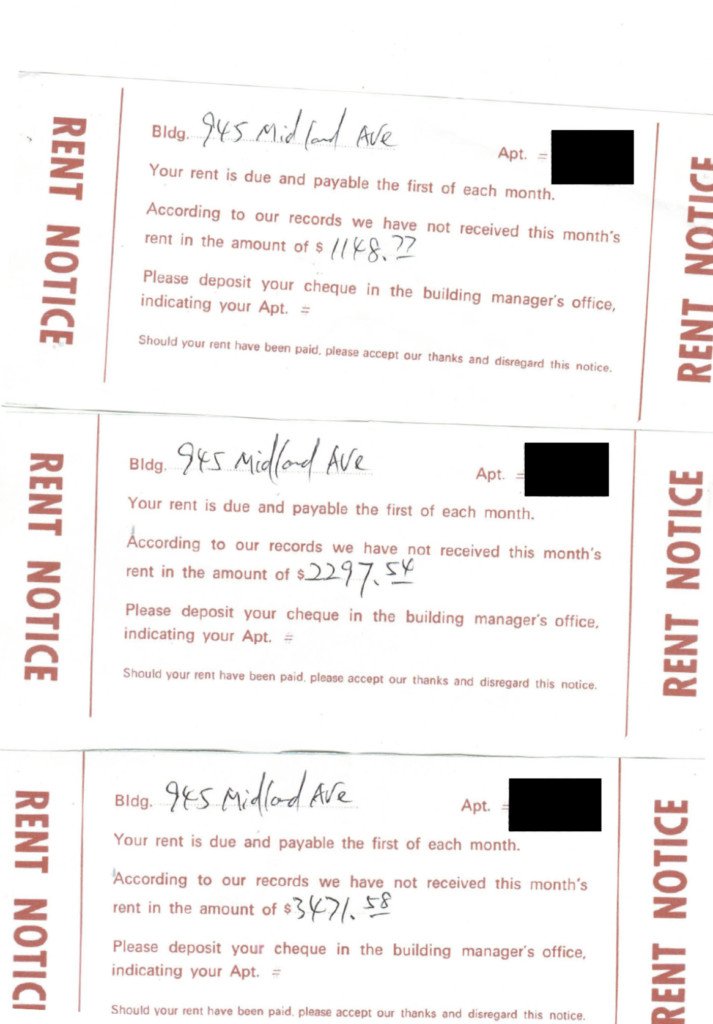

Since last April, Kiri has been unable to pay rent. According to Kiri, his superintendent started leaving rent notices, written in bright red font, every month on his door with the accumulating cost of rent.

Kiri’s superintendent escalated his tactics by starting to knock on Kiri’s door requesting rent and even calling Kiri demanding that he either provide the full amount for rent or leave.

A letter Kiri sent to his building’s superintendent after losing his job and being unable to pay rent on April 1, 2020. (KIRI VADIVELU/T•)

A letter Kiri’s superintendent sent him on April 1, 2020, after he requested a rent repayment plan following losing his job. (KIRI VADIVELU/T•)

Rent notices placed on Kiri’s front door by his superintendent at the end of each month since April 30, 2020. (KIRI VADIVELU/T•)

Kiri says the constant reminders by his landlord has made him stressed to the point where he is unable to sleep at night or concentrate on looking for another job.

The couple would find out in September 2020, that they were expecting their first child. Their doctor informed them that Thushy’s pregnancy was “high-risk,” after she constantly vomited and fainted. The couple decided it was best for her to stay home instead of working as a cashier at Walmart.

Last month, his landlord received approval to evict Kiri and Thushy, from the Landlord and Tenant Board, the provincial body responsible for disputes between landlords and tenants.

Kiri’s superintendent, sounding nervous, said he was just doing his job on behalf of the landlord. He did not agree to be named in this story. He also redirected any questions to the landlord before hastily refusing to speak about his treatment of tenants.

Homesky Properties Inc. has not responded to a request for comment.

Bahar Shadpour, spokesperson for the Advocacy Centre for Tenants Ontario, said the pandemic caused nearly a 6 per cent drop in the number of people in Ontario who were able to pay their rent in full. Shadpour said landlords in the province are taking advantage of Ontario’s tenancy laws during the pandemic to kick out low-income tenants from their affordable units.

“In Ontario there’s an incentive, a policy called vacancy decontrol, which incentivizes landlords to evict long-term tenants because they can rent out in-between tenancies,” Shadpour said. “Let’s say they [tenant] were paying $1,000 for a bachelor, the next tenant that moves in for that same bachelor without any changes to the unit, that landlord can raise that amount to whatever they like for the new tenant.”

Shadpour says Bill 184, legislation the Progressive Conservatives passed this summer amending the way the LTB runs, takes advantage of low-income tenants in Kiri’s situation. She says the legislation gives landlords the power to kick out tenants who have been faithful in paying their rent prior to the pandemic. She says landlords do this to rent out their units to higher-paying tenants.

The Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing sent a statement in response to this story defending Bill 184, saying the legislation, “mandates the LTB to consider whether a landlord attempted to negotiate a repayment agreement with tenants, before resorting to an eviction.”

Eviction moratoriums have come into effect only during stay-at-home orders in Ontario. Ontario’s New Democrats tabled a bill earlier this year that would have banned evictions until a year after the pandemic, but it failed to receive enough votes.

Kiri filed a review of his eviction in March, which the LTB approved. Kiri will have a chance this month to argue why he should not be evicted.

Just weeks before Kiri’s review, his landlord, after a year-long dispute, offered him a repayment plan. The plan requires Kiri to pay $3,148.77 a month for six months.

Still relying on government support, the plan is impossible for Kiri to pay.

Even if Kiri is not evicted, he would be on the hook for more than $13,000 in rent, another $13,000 in student loans and $15,000 in credit card debt while also paying for expenses related to his newborn.

Despite the mountain of debt, Kiri says the only thing on his mind is staying in his apartment.

“I’m doing everything I can to protect my home, that is the priority right now. I don’t want to be homeless when I have a child.”

NOTE: Bahar Shadpour is no longer a spokesperson for the Advocacy Centre for Tenants Ontario.

NOTE: This story has been updated to include the month the couple found out they were pregnant.