By Keisha Balatbat

Seventeen-year-old Javian Joy Albina was coming home from church with her family when a man and his friends started laughing at them as they walked by. Confused, her family ignored the group and kept walking.

Then they heard him say, “Look at these Asian bitches, what the fuck are they doing here?”

Albina and her family were shocked to hear this coming from a brown man, seeing as they were brown themselves, being Filipino. They were laughing and speaking in their language and when she turned around, she saw them pointing at her younger sister.

Angry, Albina defended her family. “Do you have a problem?”

They responded by reiterating their first question.

Albina was not backing down, asking them why they were saying these things.

“You guys are so fucking annoying, go back to China where you belong,” the man responded.

Albina wanted to say more but her mom stopped her and told her it wasn’t worth it. They continued home, Albina still enraged. “We’re both Asian, we’re just different types of Asian,” she thought.

This was only two years ago.

In a neighbourhood as diverse as Thorncliffe Park, it’s easy to think that people are living in a utopian society where everyone is open-minded and accepting of each other. Data from Statistics Canada’s 2016 Census of Population as compiled by the City of Toronto, states that the neighbourhood had a 79 per cent visible minority population. The top three ethnicities being South Asian, West Asian, and Filipino.

Despite the large Filipino population in the area Albina, now 19, has still had her fair share of racist experiences.

Usha George, professor at Ryerson University and director of the Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement, says that people of colour are not exempt from being racist to each other because of prejudice: “We all have in our minds some hierarchy of who is more socially proficient and who is not. We always seem to judge people, attach a label to them as we see them.”

Albina believes people adapt racist beliefs based on where they’ve grown up and the experiences they’ve had with other people of colour.

When Albina was in her elementary school days, she didn’t protest the racism she experienced. As she grew older she found it increasingly difficult to remain silent.

Living in Thorncliffe Park since she was just three, Albina became friends with people of different races, something her parents were hesitant about.

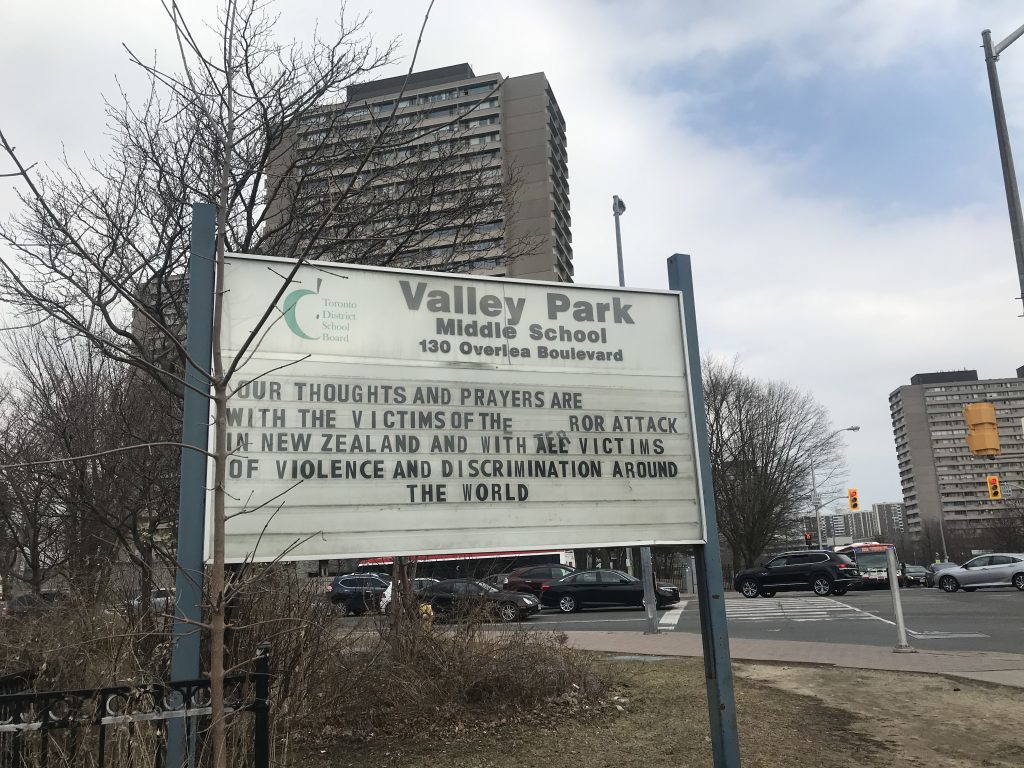

Two of the popular schools in the area Valley Park Middle School and Marc Garneau Collegiate Institute are located across from each other on Overlea Boulevard. Taken on April 6, 2019. (JRN 273/Keisha Balatbat)

Albina attended both of these schools respectively during middle school and high school where she experienced racism from kids that did not want to sit with her just because she was Asian. Taken on April 6, 2019. (JRN 273/Keisha Balatbat)

Albina was in ninth grade when she told her mom she was heading over to a friend’s house.

“What’s her background?” her mom asked.

Albina was going over to her friend’s place in order to help curl her friend’s hair for a party, but once her mom heard that her friend was Pakistani, she tried to prevent her from going.

“You can’t go there. What if they do some ritual on you?” her mom asked, assuming the worst in a culture she did not have a lot of knowledge of. Albina stood her ground, stating that she was just going to do her friend’s hair. Her mom, still set in her beliefs, said she did not trust her friend.

Growing up with strict parents, Albina liked to rebel and this situation was no exception. She went to her friend’s house anyway, but she recalls her mom being mad at her. She felt like her parents thought she was going to do something dramatic like convert religions and leave the family. “You make it seem like these people are witches. I’m just going over to a classmate’s place,” Albina remembers saying.

“We need to improve on that,” her younger self thought.

Albina continued to challenge her parents’ racist beliefs by engaging in tough and sometimes awkward conversations. “I would tell them, ‘You are in a country and neighbourhood full of other people of colour. How would you feel if someone came to your country and said you don’t belong here?’,” Albina said.

As the years went on, her parents finally understood where she was coming from and they grew to become more accepting of other cultures.

She believes the diverse community of Thorncliffe Park also played a role in her parents getting educated. Her mom frequently volunteers in the community. Through that and making friends with people of different races, she was able to change her feelings towards them.

[doptg id=”3″]

Ryerson’s professor George thinks that intercultural dialogue is an effective way of getting rid of prejudice. “If more of us can do more of that it would be nice,” George says. “Talk to each other, find out about each other. Then you kind of develop an understanding or even a bond between those people.”

Albina is not the only one who has experienced oppression in the community.

In 2015, Now Magazine wrote about Thorncliffe and nearby Flemingdon Park community members rallying together to protest Islamophobic incidents that were repeatedly occurring in the neighbourhoods. One woman was reportedly punched, had her hijab ripped off, and robbed of her cellphone while picking up her children from a school nearby.

Albina believes an increase of community gatherings and taking the time to get educated about other people and cultures can be beneficial in fostering an accepting community. “More opportunities for mixing and mingling and having conversations is a good way to sort of break the barrier of racism,” George adds.

“Try and approach other people who aren’t in your group. You’ll learn more from other cultures,” Albina says.

The international love for Bamiyan Kabob

Bamiyan Kabob, nestled between a myriad of small shops and stores, serves as a beacon to lovers of authentic Afghan food. For many in Thorncliffe Park and international food lovers, the restaurant offers a taste of the Middle East with their tasty, freshly prepared, one-of-a-kind meals. Check it out in the video below!