By Dhriti Gupta

It was an otherwise normal Saturday for Henry Marks when Canadian Olympic sprinter Ben Johnson walked through the door of his Scarborough, Ont., record store nearly 25 years ago. Tucked away in an indistinct cement and brick industrial unit near Agincourt, when Johnson first visited, Marks’ business had only recently started to become more established. Gone were the initial days where Marks would fall asleep with his head resting on the counter waiting for customers. By 1995, people could be found every weekend on the bench outside the storefront, enjoying Jamaican patties and Caribbean roti from the local West Indian joint. They would talk about everything from music to politics while Marks cued up retro R&B 45s on his turntable inside—it was a regular hangout. Still, to see an Olympic athlete he had only seen on TV stroll into his tiny shop came as a surprise to Marks.

Johnson had been looking for a record called “This Is No Laughing Matter” by 1950s-era soul singer Ray Pollard. Unsuccessful in finding it at any of the larger stores downtown, someone had recommended he go see Marks. Marks was able to find it for him and before he knew it, Johnson became friends with him, joining his club of loyal Saturday customers. The sight of his expensive car parked in the lot outside never failed to draw other customers into the store to get his autograph.

“I could safely say at one time I was his unpaid adviser,” Marks, now in his 70s, recounts with a chuckle as he adjusts his navy blue hat, flashing a glimpse of his smooth, bald head. Johnson certainly wasn’t the first customer Marks developed a strong bond with. For him, long conversations peppered with advice and warm summer evenings spent DJing personalized sets were always part of his customer service experience—and it’s what set him apart.

Henry Marks mans his double turntable at his store on Wednesday, Feb. 26, 2020. He uses this setup to play music for his customers DJ style, curating a selection of songs for them to listen to while they shop. (Dhriti Gupta/T•)

Marks lowers the needle to play one of his favourite R&B songs on Wednesday, Feb. 26, 2020. (Dhriti Gupta/T•)

Recent years have seen surges in revenue in the music industry from streaming services. The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) revealed that streaming services accounted for 80 per cent of the U.S. music market last year—73 per cent more than the figures from 2010.

While vinyl sales have recently made a comeback, they still aren’t as profitable as they used to be. According to the RIAA, in the U.S. alone, CD and vinyl sales made up 52 per cent of the market in 2010 but only nine per cent in 2019.

In Toronto specifically, music commentator Eric Alper says you can see the effects of Canada moving toward becoming “fully functional as a music streaming country.” He says that in previous years, Toronto used to have an abundance of music venues and stores, but as the city becomes more involved with music streaming, the less people truly want to go out.

“If you wanted reggae, there were six clubs for that in Toronto in the ’80s and ’90s and 2000s. If you liked folk, there were five places, if you liked rock, there were dozens of places,” he says. “Now there’s not.”

Amongst all of this, Marks recognizes the odds for a tiny record shop located in the east end of the GTA, but understands it’s his business philosophy that keeps his doors open and his vinyls spinning.

“It’s not only buying records, but I’m advising them and guiding them,” he explains. “When I got into the business, a lot of local record shops were around downtown and Scarborough…they’re all gone and I’m still here.”

While big, commercialized record stores like Sonic Boom have made a name for themselves by selling to the masses, Marks prefers his personalized approach. He feels that being able to draw on nearly 30 years of expertise about the vinyl industry keeps his customers coming back.

“I don’t want my shop to be like a record store downtown,” he says. “It’s how you handle people, it’s how you establish relationships.”

Besides, the impact of Marks’ store can be felt from much farther than the confines of Scarborough.

A map of Marks’ worldwide customer base (in red)

He remembers a warm summer night in the early 2000s when a man with a foreign accent came into the store looking for R&B soul music. While scouring the aisles for records by Roy Hamilton, Marks couldn’t help but ask him where he was from. The customer told him he was from Iran, and had just travelled through Hong Kong, where someone had recommended he visit Henry’s Records during his stay in Toronto.

“I don’t know anybody over there,” says Marks. “I’ve never been to Hong Kong.”

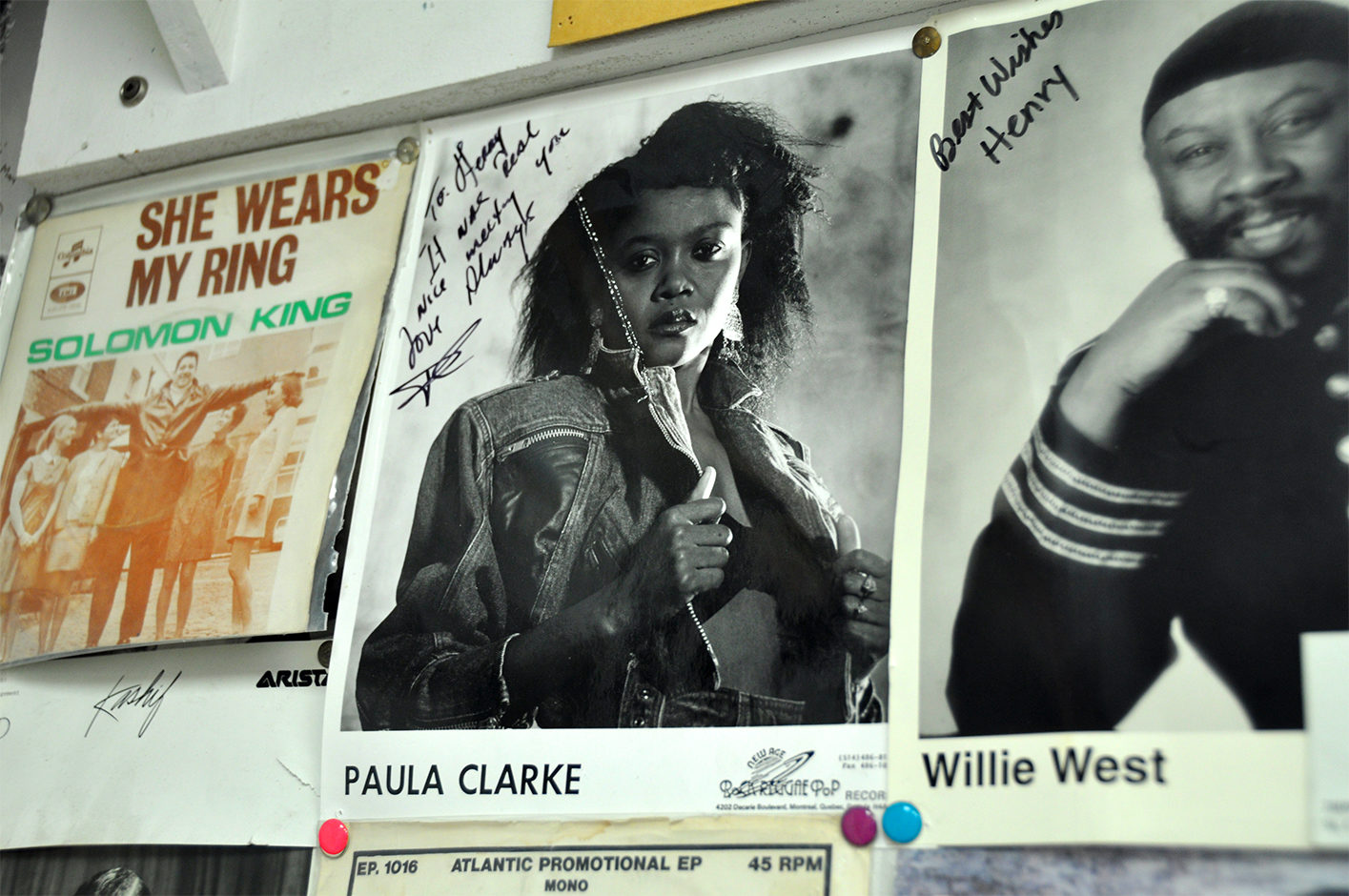

Over the years, Marks says he has met people from Russia, Germany, Italy, Britain, New Zealand, Australia and the Caribbean. Photos of friends he has made along the way and autographed headshots of musicians such as Paula Clarke and Willie West line the wall across from the front desk.

No matter who passes through the shop, he asks them what they’re looking for before nimbly shuffling through a stack of vinyls, weathered thumb looped through the holes at the centre of the discs. He carefully selects a few records enveloped in yellowing paper, and brings them to his double Teknika turntables at the front, his deep blue puffer vest swishing as he walks.

He places one vinyl on each of the black platters. Once he lowers the needle he provides the context behind each song—how they recorded that sample, how that particular artist broke into the industry—stopping every now and then to gently croon along to the music spilling out from the speaker above his head.

“Every time you sell a product, you sell a piece of you with it and that will determine if people will come back and see or even talk to you,” he says. “The record collecting family is a small one and they talk to each other.”

Marks says word of mouth is how most small record businesses stay afloat. One time, Marks found himself in the London Underground, holding two heavy boxes containing about 500 vinyls each, hoisting one more bag full of clothes on his shoulder. He travelled this way on public transit for about eight hours until he reached a rural area in Norfolk, where he was able to meet another record collector to conduct a trade.

With smaller record stores like Marks’ not having a lot of money to use for advertising or the market flexibility for price slashing, Alper says bringing a personal touch to their business approach makes all the difference.

“What you have to do is know your customer base. Really, really, really well,” he says. “There’s a sentimental value of having places like that within your community and people try to do everything they can to keep them there.”

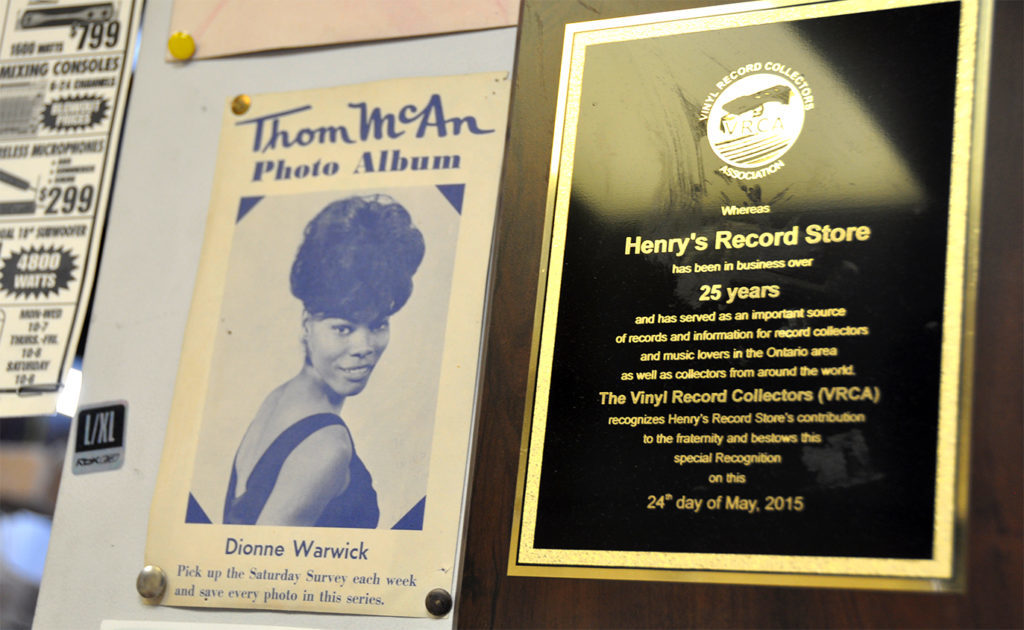

Awards line the walls at Henry Marks’ store on Wednesday, Feb. 26, 2020. He is widely recognized for his knowledge and helpful nature in the record collecting community. (Dhriti Gupta/T•)

Henry Marks speaks to a customer and friend on the phone at Henry’s Records on Wednesday, Feb. 26, 2020. (Dhriti Gupta/T•)

These days, the landline at Henry’s Records never stops ringing. From his electrician to his doctor to his neighbour, he sells records to everybody and if they can’t come in, they give him a call. Just the other day, Ben Johnson came by again to visit, reminiscing about old times. For hours they talked about music, that first time that Johnson came into the store, and as always, Marks says that Johnson was eager to receive advice on personal matters. But Marks doesn’t mind—for him it’s part of the job, and a part that he loves.

“I’m a community person. I go to funerals, I host parties, I do whatever I can to participate,” he says. “I don’t lose friends, I keep them.”