Minutes from Dufferin Grove is a studio with a mission to make traditional paper art practice accessible to all kinds of communities

By Nadia Brophy

It was mid-afternoon. The soft sound of music was playing from hidden speakers. It was something of the relaxed, alternative rock genre — a vibrato voice backed by smooth guitar strumming. It welcomed you into the vast studio space where you could spend hours taking in all of the intricate art projects, abstract paper structures and materials packed away in boxes stacked from floor to ceiling labelled Flax, Acrylic, Cotton. Pastel blue and pink paper stars hung from one section of the ceiling, twirling and swaying slightly.

Every inch of the studio is always covered in unique projects, each with a different flare and style. But one thing binds all of the structures, projects and materials together — the traditional medium of paper.

This creative space known as Paperhouse Studio is the brainchild of Flora Shum and Emily Cook, two OCAD University printmaking graduates. Their shared vision to create a communal environment for paper artists, makers and lovers alike was brought to life in Artscape Youngplace, a cultural hub just minutes away from Dufferin Grove, where it is one of many spaces dedicated to “creation, learning and collaboration.”

Since its start in 2013, Paperhouse Studio has focused on artistic education and practice by offering a number of different programs. Over the past four years, they have hosted educational workshops where people can pay to try their hand at traditional paper arts such as papermaking, which includes the entire process of creating pulp to hand pulling sheets of paper, bookbinding, calligraphy, marbling and papercutting.

See how these paper art practices are being put to use: This gallery displays projects created for Paperhouse Studio’s yearly In House exhibition, a benefit art show for emerging and experienced artists alike to experiment with the medium of paper. These projects showcase the multifaceted uses of paper for individual artistic expression.

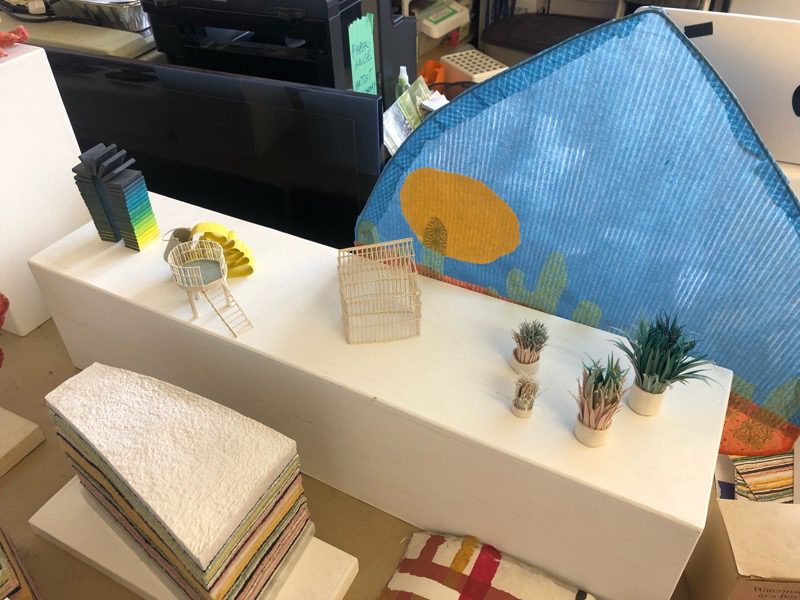

Toronto-based multidisciplinary artist Annyen Lam‘s miniature structure project, created for Paperhouse Studio’s 2016 In House exhibition using abaca, styrofoam and kozo tissue. (RSJ/Nadia Brophy)

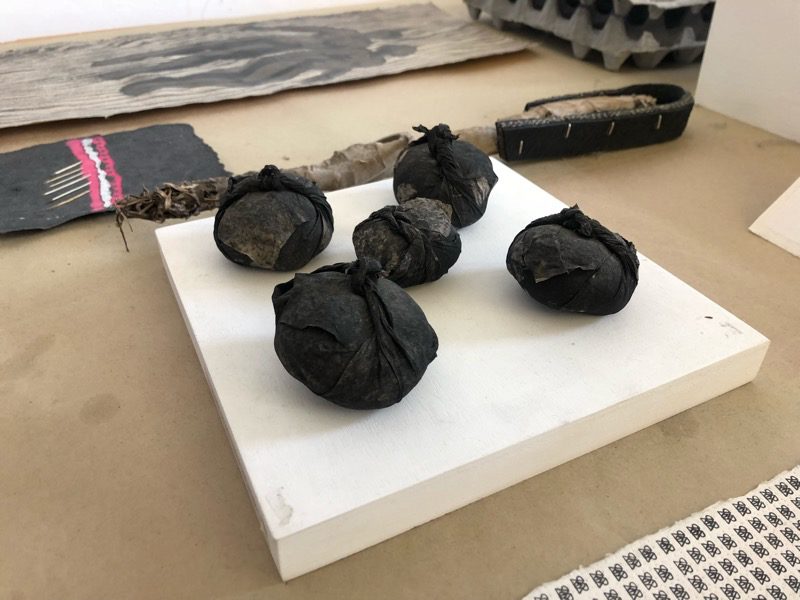

For All That Was Soft, created by Toronto-based interdisciplinary artist Meghan Price. Conveying a series of rock layers, it was created using paper, cotton, wool and cashmere for the 2017 In House exhibition. (RSJ/Nadia Brophy)

Bundled Thoughts, a “photogravure etching on flax paper” made in Paperhouse Studio for the 2016 exhibition. Created by Japanese-Canadian artist Emma Nishimura, this project used images of prisoners in Japanese-Canadian interment camps as apart of Nishimura’s Collected Stories series focused on archiving memory. (RSJ/Nadia Brophy)

Flat, created by Canadian contemporary artist Roula Partheniou for the 2017 exhibition. Made with handmade cotton and hemp cast paper, this project is a sculptural replica of an egg tray created with the intention to “shift perspective and perception” in the re-creation of common objects. (RSJ/Nadia Brophy)

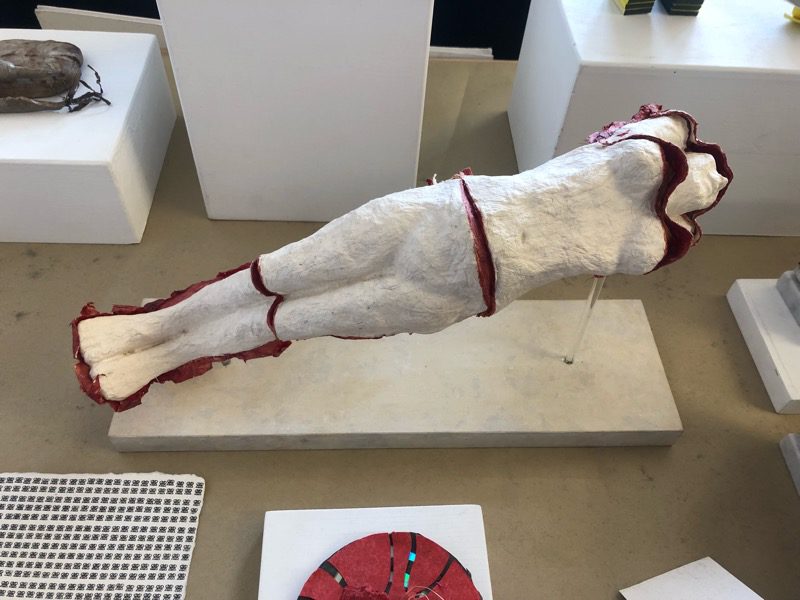

A piece in mixed-media artist Melanie Chikofsky‘s Fragments series, made for the 2017 In House exhibition using abaca, flax, winterstone, plexi rods, ink, thread and found objects to create a sculptural image conveying pain in the body. (RSJ/Nadia Brophy)

Throughout the years, Cook, Shum — and now less active co-founder Stephanie Taylor — were developing a mission that would make Paperhouse Studio a cornerstone for inclusive accessibility to art. In 2015, their team launched the Paperhouse Outreach Collective, an initiative creating artistic programs for disadvantaged groups including LGBTQ+, Deaf, Mad and disabled and BIPOC youth.

“We initially created the collective because we wanted to offer programming for youth who we felt couldn’t access a lot of the education programming in the city,” said Shum.

This programming included XYZines, a collaborative four-month art residency beginning in August 2018 between the collective, Toronto Art Book Fair, Koffler.Digital and Facing History and Ourselves, three initiatives addressing the convergence of creative education and social justice. It featured workshops and events for skill building, storytelling and hands-on projects all with the theme of advocacy against “systematic barriers and oppression” located at the Cedarbrae Library in Toronto. The program was co-designed by a council of eight youth from Scarborough who identified with one or more of the communities.

To further prioritize accessibility, according to Shum, the collective has paid for transportation for youth struggling with money to attend programs. They have also recruited ASL interpreters for Deaf participants in the past.

Since 2016, the outreach collective has also led ZIPE, a yearly program for youth to create zines — a small, self-published booklet that tells a story — located at their studio and facilitated by artists who come from the same communities.

On one sunny February day, Shum, Cook and one of the volunteer coordinators for the collective, Nigel Martin, sat together to talk about ZIPE. At a large, paint-stained table, the team gathered together some samples of zines made by past youth, giggling in reminiscence of some they particularly enjoyed.

It was clear from the spread that each zine had its own creative spin. One in particular caught my eye — a small brown paper booklet that had a circle torn into the middle with red paint around the edges, imitating a wound of some kind. Next to it was zine with a digitally designed cover image of a body riddled with bright red sores, beside it, a grey zine with no words but a simple speech bubble and an ellipsis on the cover. Another was decorated with drawn flowers and leaves. Each zine incorporated different art styles, mediums and stories that showcased a desire to express creative individuality.

“Our priorities were to create a community that could come together and learn from each other, support each other, feel less alone, feel safe, or at least brave to be in a space together to process their own individual feelings,” said Shum.

This idea was echoed by Martin, a walking example of how the collective has created opportunities for youth. Initially a ZIPE participant, Martin now contributes in developing programs designed to help people like himself gain opportunities to make art.

As a visual artist and LGBTQ+ community member, Martin credits the collective for helping him feel comfortable enough to express himself through his art.

“There’s so many other community programs where I feel like I have to suppress parts of myself or explain myself just to feel comfortable participating,” said Martin.

But at Paperhouse, Martin feels encouraged and inspired to work on his artistic career. He attributes much of this to the studio’s choice of programming facilitators.

“I thought (Cook and Shum) had done a really good job of bringing out teachers who had gone so far with their own careers and weren’t afraid to show their pride in being part of the same communities,” said Martin. “For my own career as an artist, I’m always trying to look for the ideal career path and mentors, and I find so many of the teachers were people I’d want to grow up and be like.”

Martin had expressed earlier in the day that he felt particularly inspired to practice his marbling skills, an art form commonly taught at the studio. Setting up an array of acrylic paint cups and a large water tray, he got right to work.

Cracking a small smirk, he began to open the paints — purple, black, cyan, white. Picking up a broom straw brush — a bundle of straw wrapped together on one end and frayed on the other — he proceeded to dip the frayed end into the icy white paint, just a few times, before gently tapping the brush on the back of his hand into the water tray.

Tiny white circles and stars developed on the water’s surface, but they didn’t remain stagnant — with each tap, the paint spread and turned into different shapes — stars and circles became lines mimicking waves of a rolling sea.

The studio was quiet but for the drip, drip, drip of acrylic as it met water and the tapping of plastic as Martin dipped into the colours. He interchanged them as he continued his project, watching with glee as the darker paints he added last began to swallow the layers of cyan and white, highlighting how paints can be layered in marbling.

The before and after of visual artist Nigel Martin’s experimentation with marbling on water.

Upon completion, Martin inserted a square piece of white cotton onto the surface, softly tapping it with his finger tips to ensure the paint spread to every corner of the fabric. When he finished, he lifted the square, pulling his project from the water to reveal an image of bright lines of white and cyan swirled around pools of deep black and purple.

As Martin hung his masterpiece on a drying rack in the back corner of the studio, alongside other cotton squares with their own unique patterns created in a class, it occurred to me that marbling is an art form that welcomes creative spontaneity and expression from all different kinds of artists from different walks of life, just like the place it is taught in.

Video – Art accessibility at Paperhouse Studio: The artist’s perspectives

Watch a four-minute video showcasing the projects of two paper artists who have benefited from the accessibility to traditional paper art provided in Paperhouse Studio. In addition, these artists speak about how community plays a role in the encouragement of their artistic careers.