By Sierra Edwards

On a dry Thursday morning in March, Carol Danis walked down the sidewalk over cigarette butts and past a woman sleeping in a doorway to visit a client. As an outreach worker, she had recently found housing for a client in a safe area downtown, yet had caught her once again spending time in the house Danis was trying to get her away from.

The three-storey home is rented by drug users pooling their money and referred to by Danis as a “drug den.” The space, according to Danis, is set to be torn down by the City of Toronto after a series of violent incidents. “We all sat, we had a lovely conversation, but I could just hear the violence going on upstairs,” Danis says of her client visit, explaining that to obtain drugs in drug dens like this one, women are often subjected to physical and verbal abuse.

Danis describes drug use as complex, especially for women. Drug habits are so difficult to curb that women are often drawn back to the situations they have tried to escape from. “Sometimes women just can’t get out. They just don’t have the power to get up and go.”

From 2010 to 2020, opioid-related fatalities in women increased 46% faster than in men, according to the University of Windsor’s Dr. Katherine Rudzinski. While recent years have popularized harm reduction facilities such as safe injection and drug testing sites, marked differences between men and women have been systematically ignored in the assembly of drug-centred health care. Melissa Perri, a doctoral student at the University of Toronto whose research centres on gender and harm reduction, says current harm reduction facilities tend to be gender-blind, taking a “cookie-cutter approach” that acts as a reflection of societal values. In doing so, the needs of women who use drugs are ignored.

Gender inequities that have existed throughout history directly translate into today’s drug climate. Perri says the harms associated with being a woman who uses drugs can be traced back to histories of sexism, racism and colonialism. “Embedding a trauma and violence-informed approach to care will allow women to kind of begin to heal from the decades of trauma and violence that they’ve faced,” she says.

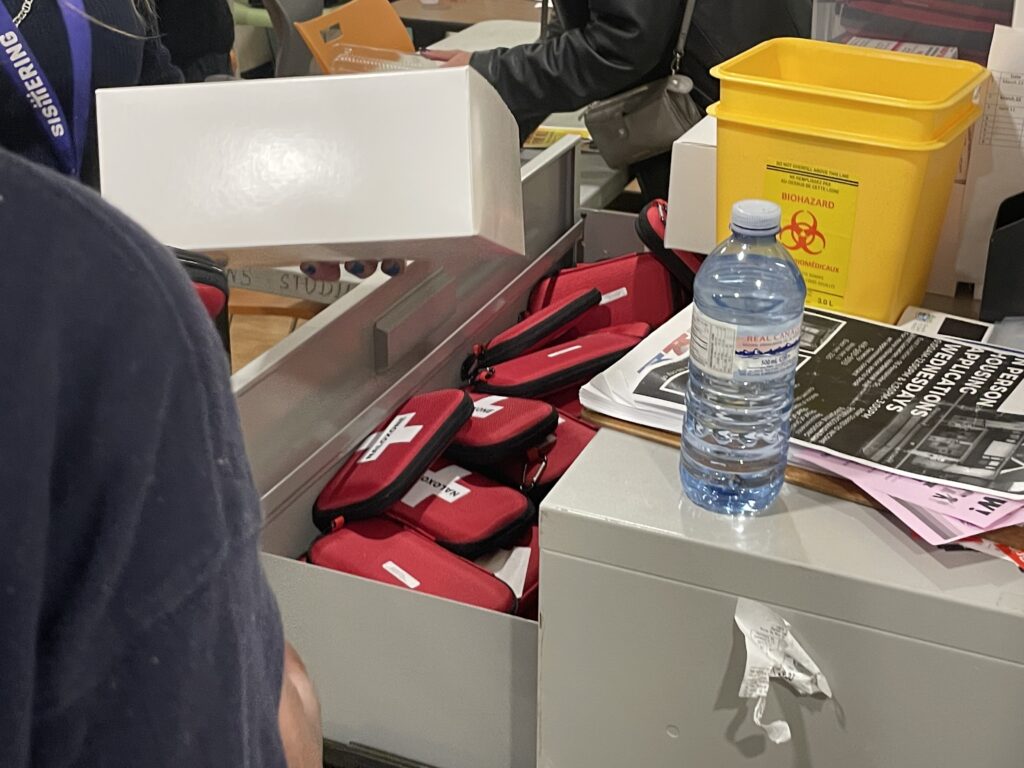

Carol Danis is the harm reduction coordinator at Sistering, an organization that provides counselling, safe drug kits, meals and housing to at-risk women and trans people in Toronto. Sistering takes a low-barrier approach, meaning it has very minimal entry requirements and provides services to whoever may need them. In her 13 years with Sistering, Danis has worked with hundreds of women struggling with addiction.

While drug addiction and homelessness plague many people in downtown Toronto, Danis says women have it the hardest. As a woman, there are more factors at play such as sexual abuse, intimate partner violence and the social shame and stigma against women who use drugs. These elements build on one another and can create harsh mental states for women struggling with addiction. “Women suffer more mental health [problems] from drug use. More anxiety, depression and of course PTSD.” Danis also says that she sees women get addicted to drugs much more quickly than men. “They are frailer than men, they do get addicted faster and easier, and they overdose quicker.”

Perri says in cases in which women are trying to get clean, male partners can stand in the way. “I have had conversations with women who have reflected on the fact that because their partner uses often, they use as well,” she says. Men often hold both the money and the power in relationships. It can be difficult to disassociate from a male partner for women who rely on them. Danis says relying on men can leave women desperate, vulnerable and at risk of violence.

For a female drug user, reporting violence is often out of the question. Contact with police may lead to victim blaming if authorities know a woman is an addict. According to the Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research, the global rate of incarceration for women has gone up by 60%, compared with a male increase of a mere 22%. Danis says police find it easier to throw a woman in jail than to solve her problem. Even when experiencing partner violence, many women cannot afford to leave their abusive other halves. “If the cops come it’s not up to them anymore,” says Danis, meaning the woman cannot control what happens when the police are involved and partners they rely on may be incarcerated. “Then what’s going to happen? Who’s going to take care of the rent? Who’s going to take care of the drugs?”.

While drug safety advocates such as Perri and Danis recommend using with another person, complexities can stem from women and men using together. Traditional power dynamics between genders mean men usually take the first hit, leaving women the second user of injection tools. “There’s a lot of needle-sharing nonsense that goes on,” says Danis. “A lot of the time women just get the washes out of it, sort of like a backwash. It’s just disgusting.” Needle sharing in this order leaves women at an increased risk of infection such as HIV, Hepatitis C and other transmittable diseases.

Aside from secondhand infection, drug use brings along a variety of other challenging health issues. Danis says a huge barrier for women is finding access to healthcare. Many doctors are reluctant to treat users unless they get off the drugs, which is not a realistic option for many people suffering from addiction. Danis believes women find it much harder to access harm reduction programs and are less likely to reach out for help. Safe drug facilities have become more prominent and more accepted, but Danis says there’s still a lack of resources for women.

To combat the issue, Perri and her research team advocate for gender transformative health care programming. They are calling for a “redistribution of resources that centres the needs of women and gender-diverse people who use drugs” that considers not only their gender but all of their other needs. She says race, ethnicity, ability and sexuality are all important to consider when formulating an optimal healthcare system.

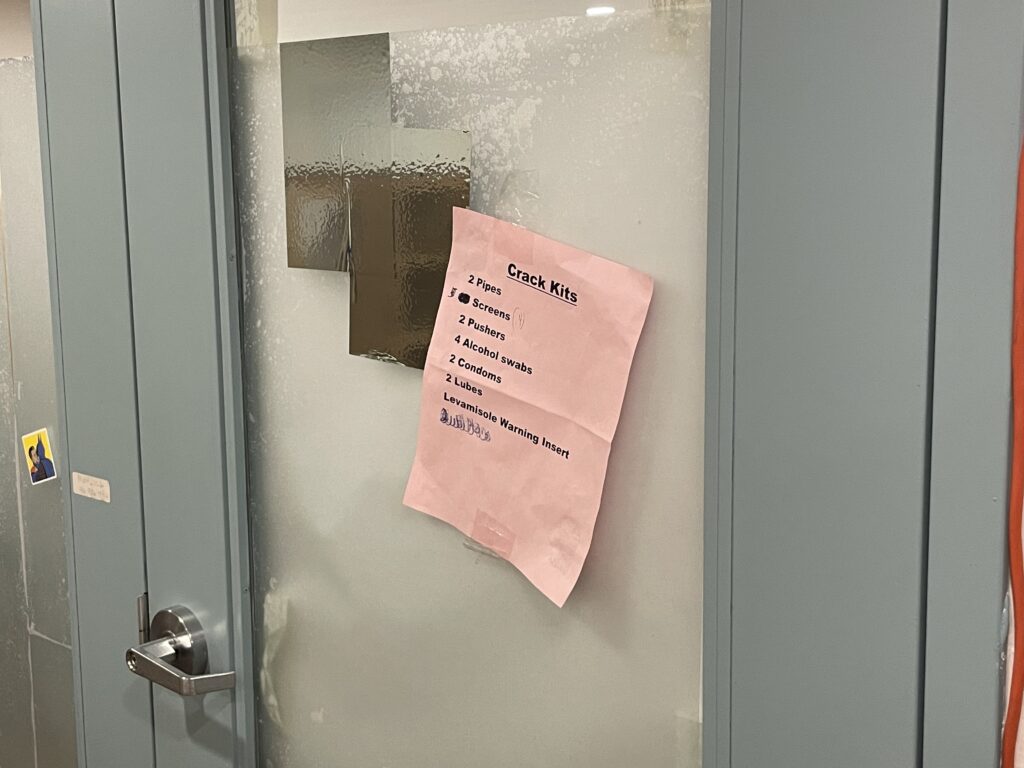

Every Thursday at Sistering, six to eight women crowd around a foldable table, forming an assembly line. They add glass pipes, condoms and paper pamphlets with helpful resources into black plastic bags to distribute to drug users. At the end of the line, a peer worker peels and sticks on the final touch, a sticker labelled “crack.”

As they work, the women catch up and share stories of their lives. A young woman with thin eyeliner tells her story of struggling to be accepted by a local women’s shelter. Another with a low, strong voice shares that while trying to quit meth, she has been diagnosed with ovarian cancer. A third woman wearing big hoop earrings and a ball cap says that though she is proud of how far she has come after overcoming her crack addiction, her recent weight loss surgery has given her such terrible body dysmorphia that she is tempted to relapse.

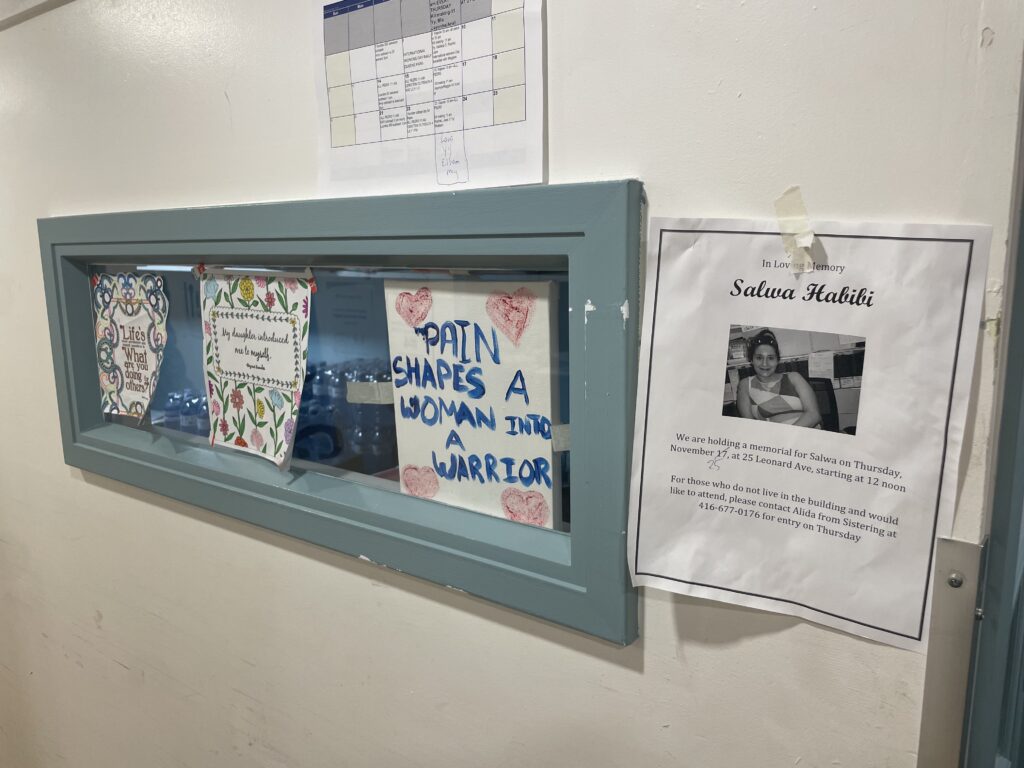

Many of Danis’ clients, and many women who facilitate or use Sistering’s facilities, have known each other for years. The longevity and depth of the bonds these women have formed is evident in their interactions and supported through their involvement with the female-oriented community that has formed through Sistering.

Agencies such as Sistering that support women experiencing drug addiction are quite literally life saving. “Using in drug setting spaces, in harm reduction spaces, and dealing in those spaces. It’s not a bad thing,” says Danis. “You know there are people there that will save your life.”