By Mercedes Gaztambide

On a cold February morning in 2012, Pauline Oseña was preparing to feed her five-month-old son solid food for the first time. Her doctor recommended that she start out with rice cereal, which typically contains rice flour and milk. Oseña smiled as her firstborn gobbled up the cereal–a good sign that he would take to the transition. On the second feeding, she noticed a peculiar rash on his arms. It was unlike the eczema that she had seen on her son before–pink mosquito-like bumps were spreading all over his body. On the third day of feeding, her son began vomiting. His arms, legs, chest, neck and face were swelling like a balloon. Terrified, Oseña rushed to Shoppers Drug Mart to pick up Benadryl–the only remedy for an allergic reaction that she knew. But when she returned, her son’s throat was sealed tight. The blood drained from her face as she bolted to the Mississauga Trillium Hospital, praying that her son’s life would be saved.

After a night spent in the hospital and a dose of epinephrine, Oseña’s son came home with open airways and a diagnosis: an anaphylactic dairy allergy.

Although this happened nearly eight years ago, Oseña’s eyes are focused on the table, her shoulders sinking forward. “It was really, really scary,” she says, almost in a whisper. “We spent a year and a half eating just steamed vegetables and rice because I was too scared to try anything else.”

After her child’s diagnosis, it wasn’t long before his allergies to peanuts, tree nuts, eggs and wheat came to light. A limited diet left Oseña and her husband wondering what chapter they had missed in the parenting handbook that dealt with life-threatening food allergies.

The EpiPen is the most commonly used device for counteracting anaphylactic attacks; a tool encompassing the measures necessary for those who have life-threatening allergies. (Mercedes Gaztambide/T•)

An EpiPen contains epinephrine, a drug that narrows blood vessels and opens airways in the lungs during an anaphylactic episode. (Mercedes Gaztambide/T•)

“We were being so careful,” she sighs, tucking her short black hair behind her ear. “I really just wanted to eat dessert again.”

So she started baking. When her son was almost three, Oseña found a basic recipe for a gluten-free, dairy-free, egg-free, nut-free chocolate chip cookie.

“It turned out really well,” she says. Her eyes are wide now, and she’s sitting at least two inches taller than she was a moment ago. “That first recipe, it’s actually what we serve now in our cookie jars.”

Oseña’s first attempt at an allergy-free dessert was with a chocolate chip cookie, and the recipe turned out so well that it became a staple at the dessert station.

(Mercedes Gaztambide/T•)

The lemon blueberry cupcake is plant-based: gluten-free, nut-free, dairy-free, egg-free, soy-free and sesame-free.

(Mercedes Gaztambide/T•)

(Mercedes Gaztambide/T•)

Over the last two years, these simple plant-based recipes have laid the foundation for Hype Food Co., an eat-in/take-out restaurant owned by Oseña and her husband, Matt Gauvin. They considered opening a bakery in 2017 to serve allergy-free treats, but the couple knew that their brick-and-mortar project had potential to be about more than just the sweets. The restaurant opened one year later, in 2018, and the pair has been committed to maintaining the allergy-free space ever since.

“It’s about the experience of eating, having a place to go and be worry-free,” says Oseña.

She is surrounded by toy trains, blocks, and tables just tall enough for a toddler to sit comfortably. There are wooden plates on the wall covered in marker and dozens of crayon designs. The works of art are adjacent to the “wall of fame” boasting at least 50 artists, mostly under the age of 10, with a couple of older, weathered faces scattered in the photo gallery.

The restaurant extends from the counter to a semi-raised dining area, painted white and black with teal-accented walls and furniture, paying homage to the signature colour chosen for the international allergy awareness movement. The CN tower painted on the back wall is lit up in a bright, off-blue colour, surrounded by Toronto street artist Emily Mae Rose’s trademark mischievous raccoons. The strong scent of espresso wafts through the restaurant, complemented by the budding scent of cooked brisket.

For many parents of children with allergies, Hype Food Co. is the only restaurant where they’ve been able to eat out as a family. Oseña recalls a family from Halifax who visited in the restaurant’s infancy, her gaze resting on the table where this particular family ate for four days straight while vacationing. “It was crazy,” she chuckles, “but that’s been the most surprising part. Just how intimate our relationships have become with customers.”

At the bar preparing food is Hanna Van Alphen, a tall, blue-haired post-grad art therapy student. She recognizes nearly everyone who walks in.

“Customers have come to me saying: ‘Thank you, we haven’t been able to eat out as a family for 10 years,’” says Van Alphen, who has worked at Hype since it opened. “They were so overwhelmed that they could spend time out in public as a family without risk. As a business, it’s just so rewarding.”

Each bowl starts with a choice of base: mixed greens, zucchini spirals or brown rice. This order starts with mixed greens.(Mercedes Gaztambide/T•)

There are 11 fruit and vegetable options to add to the bowl before protein. Here, Van Alphen includes some shredded carrots. (Mercedes Gaztambide/T•)

After the protein has been added, one of Hype Food Co’s house-made sauces is drizzled overtop. The coconut green curry is a favourite. (Mercedes Gaztambide/T•)

She strikes up a conversation about her thesis with a stocky man covered in tattoos, who orders chicken on a bed of mixed greens and an oat milk latte. Gauvin, Oseña’s husband, compliments the tattooed man’s sleeve and saunters around the restaurant, listening intently to each customer’s story.

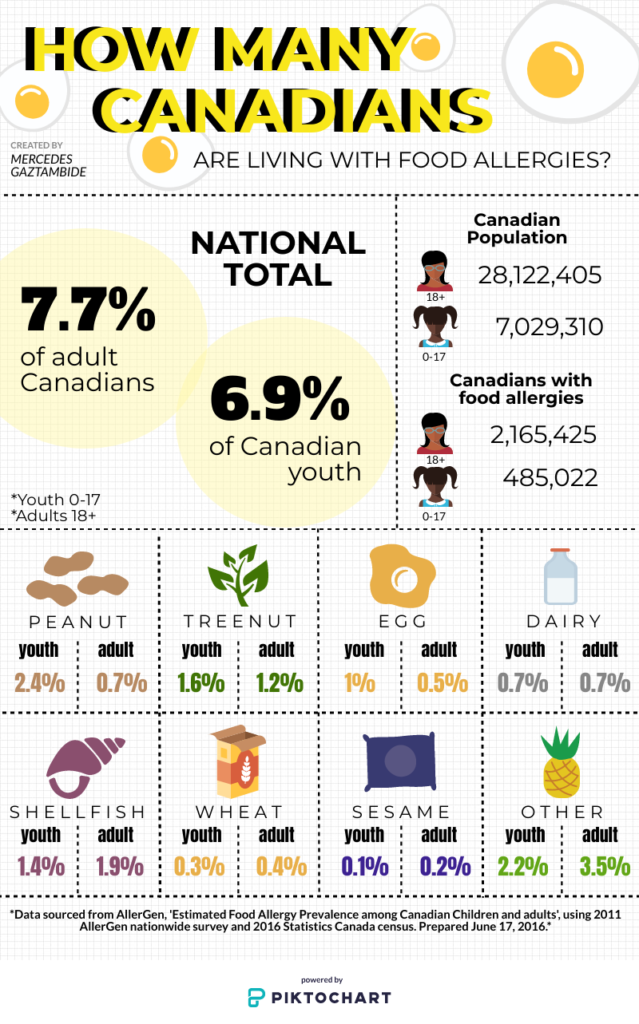

This is an integral part of Oseña and Gauvin’s business. They want to make sure their menu matches customer demand. Food allergies affect 7.5 per cent of the population, according to Food Allergy Canada (FAC). Peanut allergies alone affect about two in 100 Canadian children. Food allergy anxiety is also common among individuals and families, according to research included in the 2019 National Food Allergy Action Plan. Almost half of the respondents in the study described their food allergy anxiety level as an eight out of 10 or higher.

The first time Danielle Siobhan visited Hype, she just looked around without eating anything. She explains that she’s had bad dining experiences in the past, particularly due to her soy allergy. Chefs would tell her that food was safe to eat, but when she checked the ingredient list herself, soy was listed.

On her second visit, Siobhan felt comforted by the company’s transparency and decided to try her luck – and she hasn’t looked back since.

“For the first time in years, I go to a restaurant and feel excited,” she gushes. “Going to Hype makes me feel like any other person who stops to grab supper on the way home from work.”

Kristin Ali has two children, one of whom has severe food allergies. She’s a lawyer with a busy schedule, and Hype is a weekly staple for her family. Ali explains that the restaurant has become the unofficial meeting spot for families involved with a social media allergy support group that often comes up in conversation at Hype.

“So often I will go there and someone will be like, ‘Hey, are you Kristin?’– all these people you’ve spoken to online, but never met,” she says. “Even if you live on opposite ends of the city, everybody goes there.”

Ali says she feels recognized by staff when she and her family come to have a meal. “They remember my daughter’s food allergies,” she explains. “There is nowhere that I feel as comfortable or as safe to eat with my kids.”

Teal couches, accent walls and tables adorn the restaurant to represent the globally recognized colour for allergy awareness. (Mercedes Gaztambide/T•)

Train systems are a favourite toy for kids at the restaurant, encouraging thoughtful building, patience and attention to detail. (Mercedes Gaztambide/T•)

Oseña decided to install ‘draw on the wall’ boards after her daughter took a permanent marker to her kitchen walls. (Mercedes Gaztambide/T•)

Pictured on Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2020. (Mercedes Gaztambide/T•)

It’s been two years since Hype’s grand opening, and while the restaurant has made strides in the industry, the path to success hasn’t always been easy.

As Oseña reflects on their opening weekend, she raises her eyebrows and leans back in the booth. “We ran out of food and had to close early on the first day. That was a huge operational eyeopener.”

She remembers sitting down with her husband for the first time after closing, surrounded by dirty dishes, toys, and empty containers, feeling like they had just thrown a wedding, and had to do it all again the next day.

“But, it’s a satisfying exhaustion at the end of every single day. We have such amazing, appreciative customers, and you’re just so happy to be there for them.”

A lot has changed since that frightening February morning in 2012. Oseña’s son is now a confident eight-year-old who knows how to take care of himself. He eats regularly at Hype, and he’s proud of the space his parents have created. Although his family’s business provides a safe place for him to eat, he’s already adopted the rigorous responsibilities of any Canadian living with food allergies: carrying his EpiPen everywhere he goes, reading ingredient lists and staying alert in the presence of allergens.

“Kids with food allergies… it’ll amaze you,” Oseña says, raising her eyebrows. “They just know.”

“He says he wouldn’t change a thing.”