By Ariel Brookes

Inside the waiting room of the Yellow Dog Music School, the lively melody of the electric guitar and the deep pulse of the drums can be felt in the vibrations in the walls. The drums and guitar aren’t playing in sync, they are coming from two different practice rooms.

The chaotic feeling of the two different melodies is contrasted by the soothing sound of the piano coming from the other practice room.

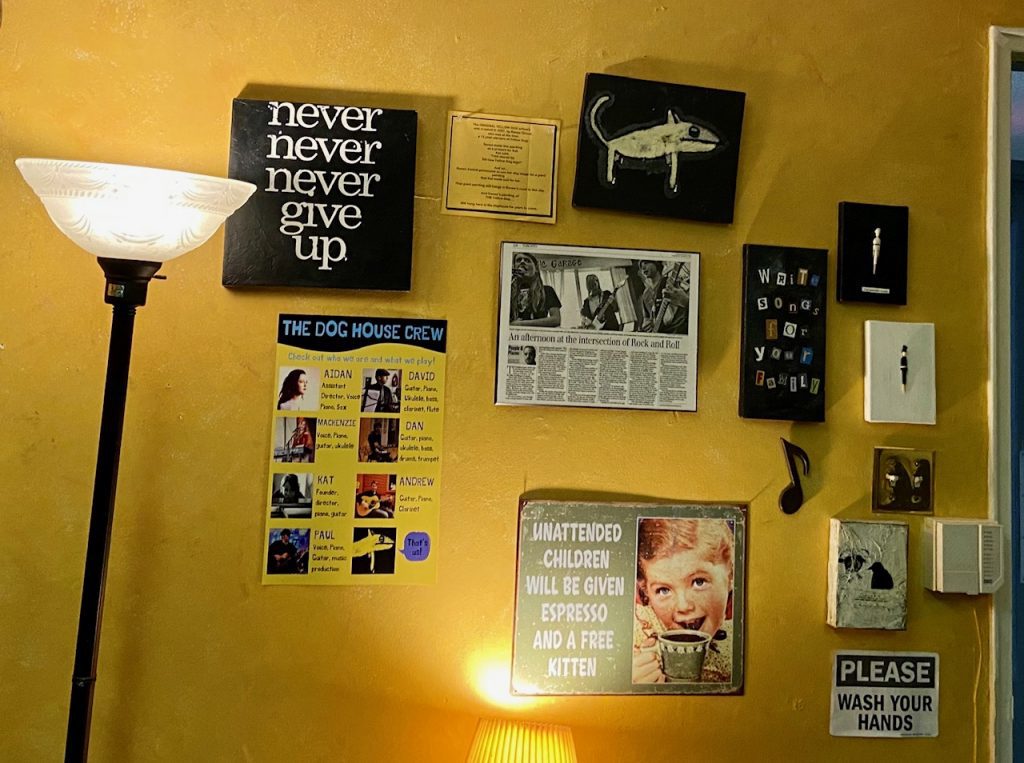

Katrina Anderson walks out of her office, offers a warm smile and introduces herself as Kat. She is the owner and founder of Yellow Dog, which is located on the second floor of a two-storey building at Bayview Avenue and Moore Avenue.

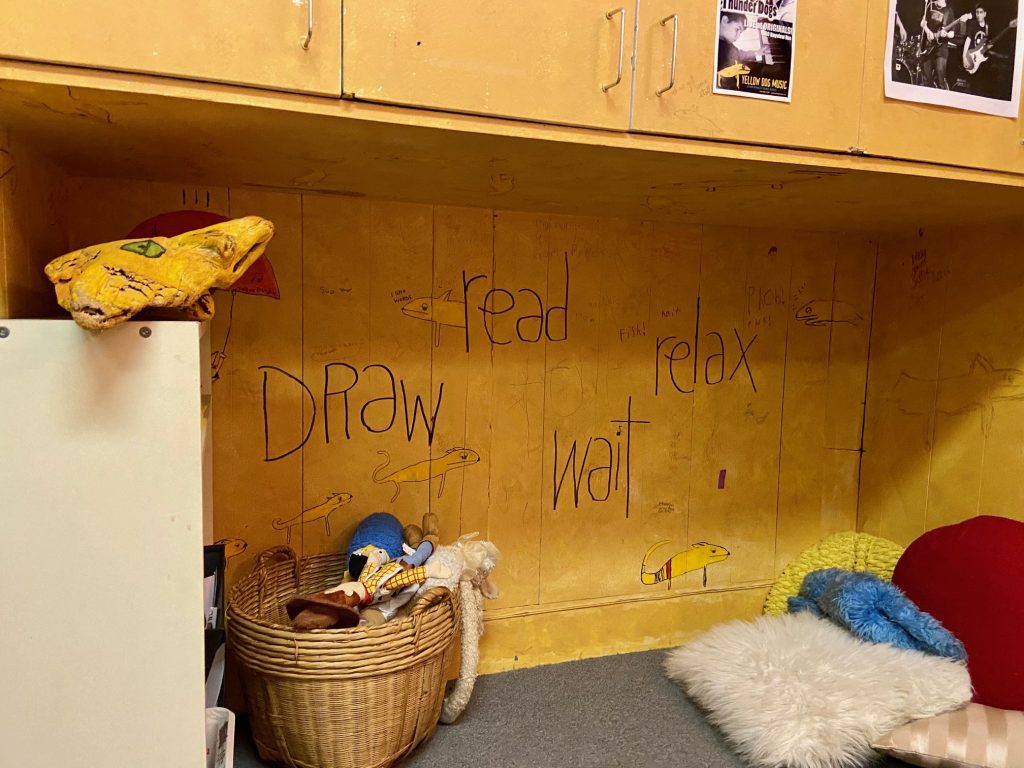

The GTA is home to over 200 music schools. However, they lack Yellow Dog’s bright yellow walls and small children’s play area made from the underside of a cupboard unit.

Anderson started Yellow Dog in 1990 as an alternative to the strict and regimented approach to music education she saw playing out.

“The traditional way is great for some. It serves a purpose for sure. But it is not for everybody. So, what is there for someone who doesn’t fit that mould? That is why I wanted to make Yellow Dog especially for anyone learning outside the box,” she says.

She strives to cultivate creativity and encourages students to learn music they love in an environment that is judgement free.

“When people first sign up, we get them to create a list of songs they want to learn. They are learning exactly what they want to play,” says one of the guitar and piano teachers David DeDourek.

Running the school hasn’t been easy for Anderson. She initially started the school with her partner, and when they split up, she bought out his half of the company. Having just doubled her workload, she was also raising her newly adopted daughter with full custody. And only adding to the stress, her daughter had come from a violent and abusive household. Anderson, while now raising a traumatized child, managed to keep the school running almost completely alone.

“I had to financially hold a house and a child, so the business was my bread and butter. It had to work,” she says.

Despite the stress of this experience, Anderson’s daughter has taught her a lot about the way she teaches. Her daughter helped her realize the importance of cultivating creativity in children.

“There I am raising a traumatized child, and you get to really feel that children need to be held extremely carefully. It made me really want to give every child that came in, traumatized or not, a space be where they felt safe and felt they could be themselves,” she says.

“My daughter is really creative and watching her just helped me realize that kids are innately creative, but it just gets shut down. The adults in their lives don’t spend too much attention nurturing their imagination.”

Despite the school’s childlike atmosphere, students range in age from four to 70. Co-director Aidan Farrell says that some of the best moments teaching have been with adult students. She says the school has some adult students who had given up music at a young age and are now re-discovering it as a hobby.

Farrell says a student in her 60s quit piano when she was young after failing a test.

“She felt so dejected and felt like she wasn’t good enough and had done something wrong. So she stopped playing piano even though she loved music,” says Farrell.

“It has been really cool working with her and having her tell me how much she appreciates being able to re-open this passion that she has in her life in a way that is really creative and positive. She had kind of the opposite experience before.”

At Yellow Dog, teachers strongly encourage improvisation and composition. They also allow students to learn by ear rather than with sheet music. When students do use sheet music, they aren’t pressured to follow the exact written notation.

“If they play a note that isn’t on the page, I never tell them it’s wrong. I feel like that could be so damaging. I always say, ‘That sounded really cool, but that wasn’t the note that’s on the page. But who says you can’t play it?’” says Farrell.

In one of the classrooms, Farrell is teaching piano to Alyssa Goodrham McLaine who is playing and singing softly My Heart Will Go On by Celine Dion. Goodrham McLaine’s voice is just loud enough to be heard above the keyboard piano.

“I am sorry that was so bad,” she says when the song ends.

“Oh my god don’t be sorry! That was so good. I am so impressed,” says Farrell with a smile.

“Thank you,” says Goodrham McLaine.

She plays the song again. Like her first attempt, she starts off quietly. When she gets to the chorus her voice ascends. A smile creeps onto her face as she finishes the song.

Aidan Farrell and Alyssa Goodrham McLaine in one of the classrooms at Yellow Dog Music School on March 3, 2020. Alyssa was taking a piano and singing lesson with Farrell. (Ariel Brookes/T•)

Alyssa Goodrham McLaine and Aidan Farrell in one of the classrooms at Yellow Dog Music School. While teaching Farrell never tells her students that they played a wrong note. Instead she tells them that the note they played wasn’t on the page. (Ariel Brookes/T•)

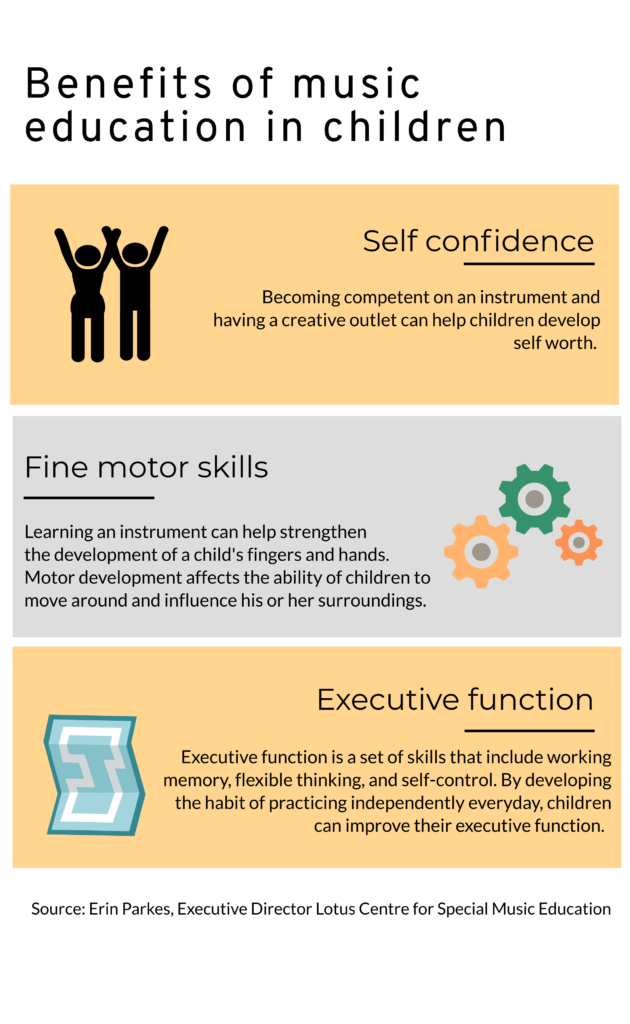

Music education is extremely important, particularly for child brain development, says Erin Parkes, executive director of Lotus Centre for Special Music Education. Lotus Centre for Special Music Education is in Kanata, Ontario. Parkes says that learning music can help development in self confidence, fine motor skills, and executive function. Executive function is a set of skills that include working memory, flexible thinking, and self-control.

“Executive function is the brain’s ability to prioritize, plan and strategize. The student has to practise everyday and they are usually learning strategies for how to practise,” says Parkes.

In the waiting room at Yellow Dog is 14-year-old Clover Long. She doesn’t try to cram herself into the already crowded bench, but rather leans against the wall. Her eyes are glued to her book of sheet music. She only looks up to the sound of the doors opening for her lesson.

Long says she loves coming to the school and is motivated to build her skills on the piano. She says that because she is learning music she is already interested in, she is more motivated to practise. She used to take classes at a different music school but feels much more welcome at Yellow Dog.

“I feel like I am improving. I am a lot less stressed about it, which is good and that also compels me to do it on my own time. At the other place, I got stressed about it sometimes, but that doesn’t happen at all here,” she says.

Parents of students at the school say that the school is a great environment in which to learn. Cameron Steinman’s daughter Heidi takes guitar lessons at Yellow Dog. He says that the teachers are fun and age appropriate and compared to his family’s previous experience with music classes, Yellow Dog is much more engaging.

“At this age, it is so important that it is child driven and it is something they are passionate about, rather than it being something they are being forced to do by their parents,” he says.

“When the lessons are dry and it doesn’t compare adequately to all the other types of stimulus they can get doing other activities, they are going to disengage. Comparatively speaking, this is a much more interesting experience for them.”

Anderson also tries to work with families that attend the school who may be struggling financially. She recently had a student who was going to stop coming because their family couldn’t afford the classes anymore. Anderson said the family could pay with a favor instead and they could pay her back later.

“She has been coming here for years so we couldn’t let her go. That would be criminal to say, ‘oh you couldn’t pay, see ya.’ That child will have had more music because Yellow Dog helped her. And what does it cost us? Whatever,” she says.

DeDourek says that Anderson doesn’t run the school for money, she runs it make people happy.

“She does people favours and then she will thank the person she is doing the favour to,” he says.

James Kivenko and David DeDourek at Yellow Dog Music School on March 3, 2020. Kivenko has been taking lessons at the school for almost his whole life. (Ariel Brookes/T•)

James Kivenko and David DeDourek at Yellow Dog Music School on March 3, 2020. Kivenko says Yellow Dog Music School is a second home. (Ariel Brookes/T•)

In the days of social distancing and self isolation due to the COVID-19 outbreak, the school has been running virtually with lessons over video chat. Anderson says that despite the need for social distancing, the school is managing.

“We are surviving and actually almost thriving during this pandemic as parents look for ways to keep their kids’ lessons going,” she says.

As for the future of the school, Anderson in the next five years will be leaving her job as director and will be giving the position to Farrell. Anderson is working part-time as an artist in the Blue Mountains near Georgian Bay. In a few years she would like that to be her main career while remaining the owner of Yellow Dog.

In the meantime, she continues to support students and teachers and is working to go beyond Toronto. Her goal is for teachers at the school to be able to lead music classes in community centres and youth homes around Ontario. Ultimately, she would like to continue to spread music to children of all backgrounds.

“I want to grow them and raise them to be colourful human beings. That is the core.”