By Michael F. Quaranta

Standing up against the rail of the ferry, I began to regret not taking refuge in the passenger cabin while I’d had the chance. Rain drummed up against the hood of my jacket. A strong gust of wind pushed in from my left. On the approaching island ahead of me, houses stood scattered along the edges of an open grassy field; behind me the toes of Toronto’s skyline poked out from under the heavy blanket of fog. The ferry slowed, docked, and unloaded. I took my first slippery step out onto the platform. Only a couple of kilometres of walking to go.

Take your right hand, extend it directly outwards, and close all your fingers into a fist except for your thumb and pointer finger; they represent the Toronto Islands. The ferry was dropping me off at Ward’s Island, which is at the tip of your pointer finger. I had to walk all the way down to that web of skin between your thumb and pointer finger.

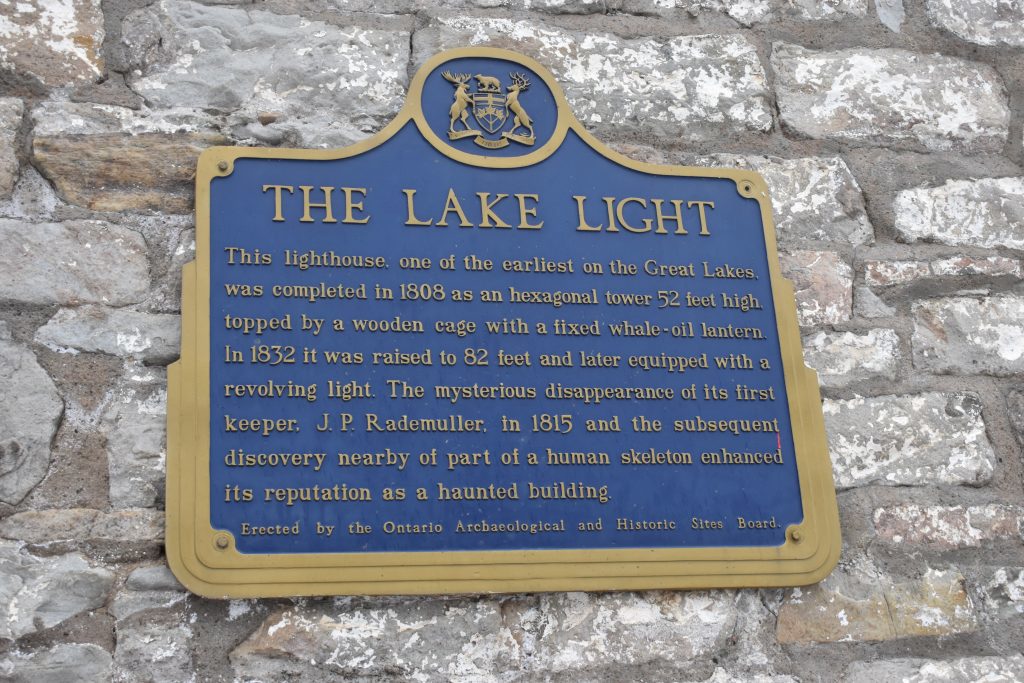

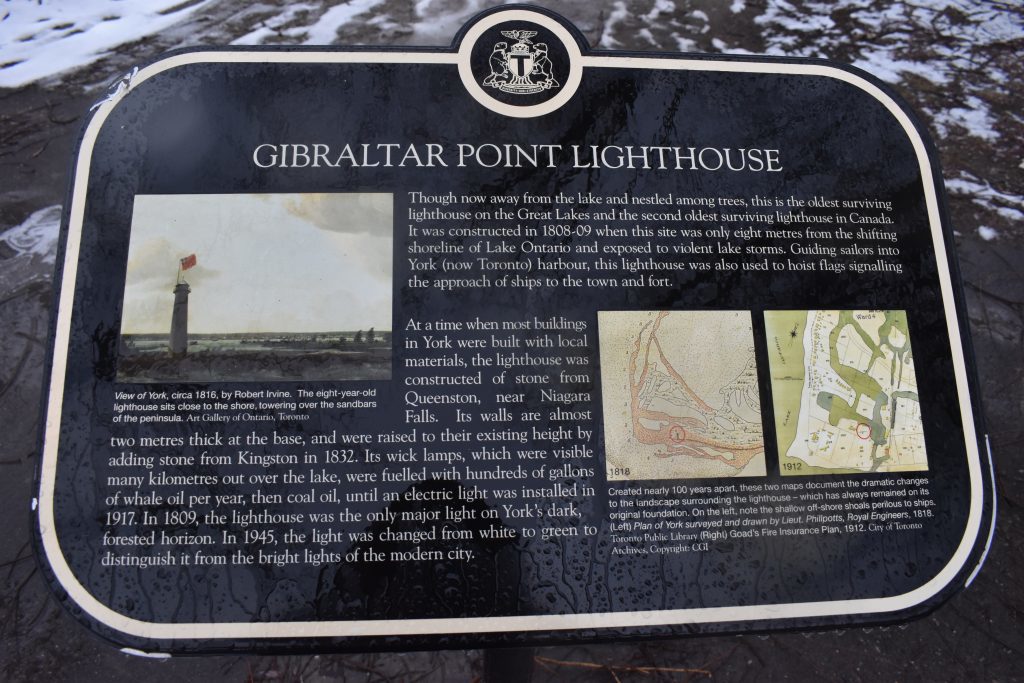

The Gibraltar Point Lighthouse has stood on Toronto Island for more than 200 years. First constructed in 1808, the lighthouse is the oldest building in Toronto still standing on its original foundation and is the second oldest lighthouse on the Great Lakes. That’s not its only claim to fame; according to some, the tower is haunted by the ghost of its first lighthouse keeper John Paul Radelmueller.

“In all likelihood,” Cappel went on, “he was murdered.” But the story does not stop there. The fourth lighthouse keeper, a man by the name of George Durnan, allegedly found human remains nearby. “Some stories say it was a jawbone,” says Cappel, “Some stories say it was a skull. Even other stories say it was an entire skeleton in a coffin. So, you know,” Cappel chuckles, “believe what you like.”

I got the impression that Cappel is rather skeptical of the whole tale; while he concedes that Radelmueller was likely murdered, he refers to the whole thing as a “human interest story”. Although technically considered the lighthouse keeper, Cappel is really more the building’s custodian.

Cappel explained that a lighthouse keeper’s job, back in the day, would have been very taxing. “In the mornings, you would have trotted up the tower, which is about five-and-a-half stories, so a bit of a walk,” began Cappel. “You would have carried pails of whale oil upstairs.” The lights in old lighthouses were kept lit using whale oil, so it was crucial that there was a sufficient amount kept in the lantern room.

“Then you would have cleaned the lighthouse,” said Cappel. This would involve anything from sweeping or painting the lantern room to actually cleaning the light itself. Daytime maintenance was essential for keeping the lighthouse lit every night. “It would have taken God knows how much out of his day. It was a 24 hour a day job as far as the paymasters were concerned.”

In the evenings, the lighthouse keeper would have climbed the tower again. “He would have trimmed the wicks [of the lamps], lit the lamps, and made any last second adjustments.” After everything was taken care of, the keeper would have gone home, which was only about 100 feet away. But he would have kept an eye out, checking on the lighthouse a few times every night. The light going out in the middle of the night “would have been a great crime,” Cappel concluded. Much in the same way that a lighthouse draws a ship back to shore, it would draw the keeper back to it hour after hour, day after day.

The lighthouse was decommissioned in 1956. Cappel explained that with all of the new bright lights of Toronto’s skyline in the background, the lighthouse was drowned out. It became difficult to pinpoint the lighthouse in the vast constellation along the horizon; ships began to rely on their own navigational technology and the added light of the city to find their way in. Trees began to grow in front of the lighthouse; it became obsolete. Were it not for people like Cappel, who now maintains the structure and educates the public on its importance, who knows what would have happened to it.

I tossed these ideas around in my mind as I walked. There was no one to talk to, save the few workers employed by the city that were doing maintenance work on the island. Waves crashed in the distance. There were lots of trees on the island, the most green space in Canada I’d seen since moving to Toronto last year. I don’t get out much these days. I lifted my head to inspect the trees, and there it was.

I had two immediate thoughts. My first observation was the mesmerizing CocaCola-red paint on the cupola. I had never seen a photo of the lighthouse in colour; the paint looked very fresh. As soon as I snapped myself out of the trance, a second observation dawned on me: it was a lot smaller than I was expecting.

I continued my approach. I lost sight of it in the trees once or twice, but it always popped its head back out, as if to tease me. I turned onto the trail and slowly approached it. I don’t know why I walked it so slowly, but I did. Maybe it was to savour finally reaching it. I had a pit in my stomach, but maybe that was because it was now getting close to noon and I’d skipped breakfast.

I walked to the door, which was painted the same red as the lantern room, the room up at the top of the lighthouse. I looked straight up at the sky, then back at the door. I jiggled the handle. It was locked. I smiled. “That’s okay,” I thought to myself. I knew I’d be back.

Only, I never did go back. I never made it to the top of that tower; I’ve not even set foot on the Toronto Islands since that day. A deadly disease, COVID-19, swept through the city, forcing me to leave the country and return home. The incompleteness of my trip that day still haunts me.

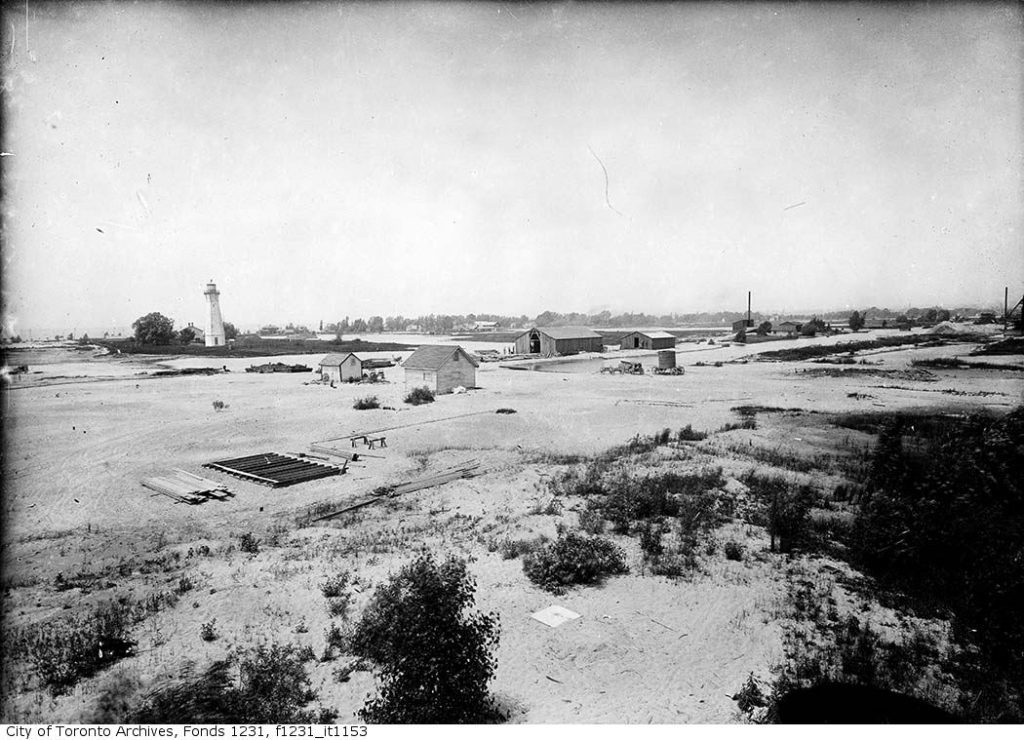

A panoramic view of part of Toronto Island and Gibraltar Point Lighthouse in 1909. This photo is part of the James Salmon collection in the City of Toronto Archives. PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

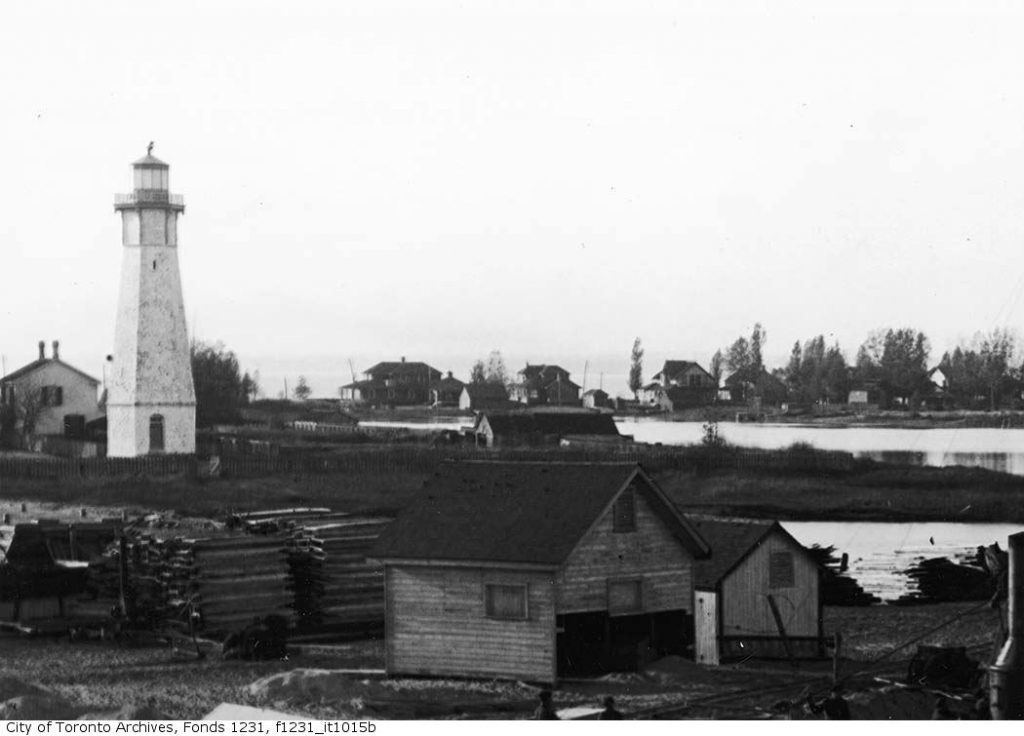

Gibraltar Point Lighthouse and the surrounding landscape on Nov. 5, 1909. This photo is part of the James Salmon collection in the City of Toronto Archives. PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN

The view from directly below of the Gibraltar Point Lighthouse on Toronto Island. The photo was captured on Monday, March 2, 2020. (Frank Quaranta/T•)

The eastern side of the Gibraltar Point Lighthouse on Toronto Island. The photo was captured on Monday, March 2, 2020. (Frank Quaranta/T•)

The western side of the Gibraltar Point Lighthouse on Toronto Island. The photo was captured on Monday, March 2, 2020. (Frank Quaranta/T•)

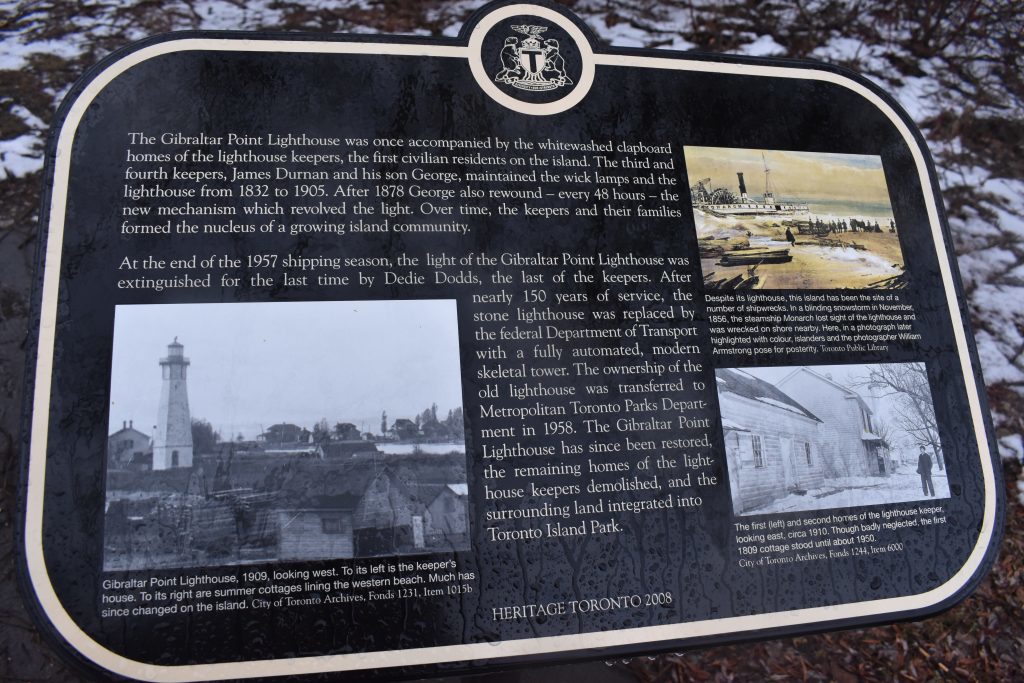

A plaque commemorates the history of the Gibraltar Point Lighthouse on Toronto Island. The photo was captured on Monday, March 2, 2020.(Frank Quaranta/T•)

The first of two informational markers directly in front of the Gibraltar Point Lighthouse on Toronto Island. The photo was captured on Monday, March 2, 2020. (Frank Quaranta/T•)

The second of two informational markers directly in front of the Gibraltar Point Lighthouse on Toronto Island. The photo was captured on Monday, March 2, 2020. (Frank Quaranta/T•)