By Carolina Pucciarelli

Allan Symons can’t pinpoint when he started collecting clocks. These days, he’s on the hunt for a pink Snider 1950s Spider Electric Wall Clock. He’s already found the blue and brown models, and needs the pink one to complete the set of small analog clocks, each with 12 concave metal legs and rounded colourful ends. He almost nabbed one in a bidding war a few years back, but the price was steep. Now, he wishes he’d bought it.

For nearly 21 years, Allan has done every job imaginable at the Canadian Clock Museum, home to several lifetimes worth of clocks, like the Snider Spiders and the Westclox alarm clocks, showcasing over 18 Canadian clockmakers.“I joke that my hat’s got 23 labels and I just rotate it around because I am the president, the executive secretary, the manager, the curator, the assistant conservator, the bookkeeper… ” he said, standing near the museum’s gift shop after a tour.

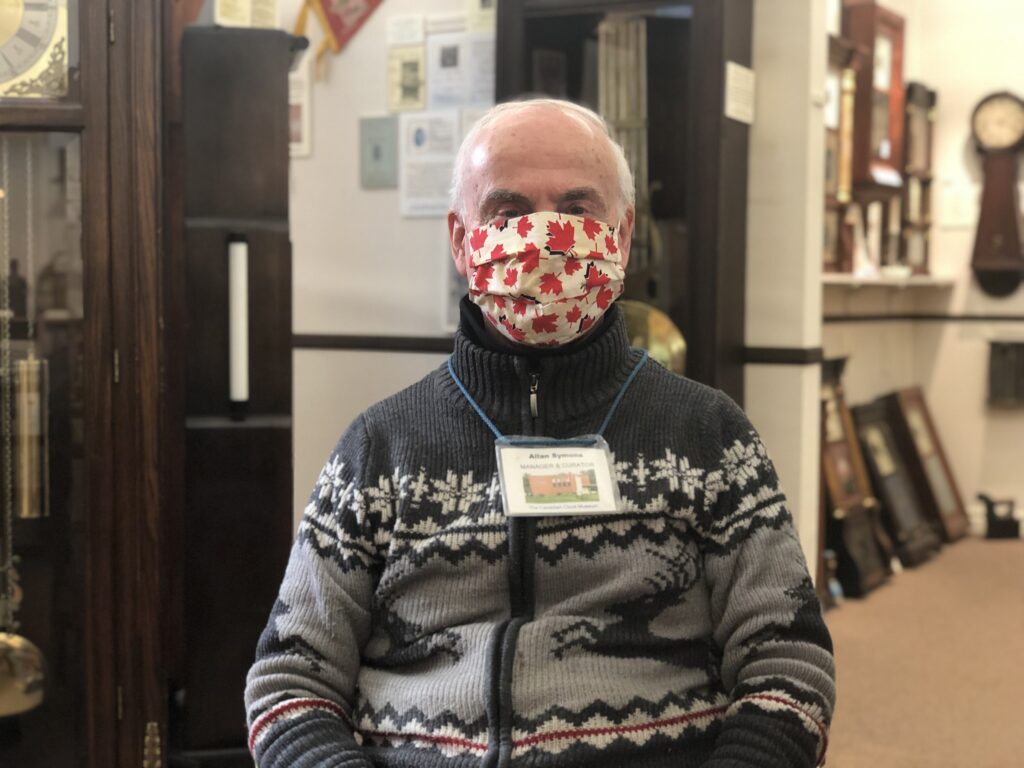

It’s an odd career choice for someone who admittedly didn’t excel in history at school. But from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Tuesday through Saturday, the museum’s founder guides visitors through the eight rooms on the exhibit floor that house timepieces dating back to the early 1800s. On a recent day in early March, the sound of grandfather clocks chiming the Westminster Quarters and the metal marbles of the rolling ball clock accompanied his voice as he described how his personal collection of 600 clocks has grown to more than 3,000 artifacts at latest count. Sitting on a stool near the nook of reference books, arms crossed, in the middle of the modified brick-and-mortar split level revamped church, he sported a maple leaf print face mask and knitted deer sweater, and had a name tag loosely hung around his neck. A bright orange neon glow emanated from a diner-esque electric wall clock, not far from an eye-catching old school employee punch clock and a painstakingly detailed 1934 ‘Tramp Art’ clock.The clock museum — Canada’s only one — is in Deep River, a rural Ontario town of 4,500 people. This fact is perhaps as unusual as a 78-year-old former nuclear scientist running the show.

“We only average 600 to 700 [visitors] a year, mostly in the summer, some tour groups,” Allan explained. “Tour buses don’t stop in the Valley. Forget about Deep River!

Over the years since opening in May of 2000, the museum’s renaissance man has seen some memorable visitors, from a hearing-impaired couple whose tour consisted solely of communicating by pen and paper, to a man who tried bargaining for discounts at the gift shop, to four busloads of people who got stranded in town.

Gary Fox, news editor at the Ottawa chapter of the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, has been in the clock business for many years and says he has yet to come across a collection quite like Allan’s.

“A friend of mine once said that collecting is a mild form of insanity. In light of that perspective. Allan did something admirable, or perhaps even a little crazy,” said Gary, who is also a longtime friend of the museum owner.

Born and raised in Kingston, Allan graduated from Queen’s University with a degree in Engineering Chemistry in 1965 and a PhD in 1969, and landed a job at Atomic Energy of Canada Limited, now called Canadian Nuclear Laboratories. Its biggest laboratory straddles Deep River and neighbouring town of Chalk River. After a 27-year career, he retired on a random Friday in 1999. The following Monday, he enrolled in a tourism workshop, a diversion that would play a key role in preserving a part of Canadian history.

The museum is housed in the former Calvary Pentecostal Church, established by well-known Canadian televangelist David Mainse, host of the long-running TV show, 100 Huntley Street. The church was for sale in 2000 when Allan was looking for a place to house his clocks and start the museum.

“So I remember cycling up, opening the front door, fingers crossed the way I remember. And the pastor at the time was in his office, which is my ‘full of everything’ office now… And I asked something like, ‘Has it been sold?’ And the answer was no.”

Today, a bell-chime sounding electric door alarm notifies Allan, who can usually be found in his office, when visitors arrive. He takes his time welcoming them, ensuring they’re aware of COVID-19 protocols and offering to guide them through. The short stairway that used to lead congregants from coat check to the chapel is much quieter these days, and leads to the exhibition floor. Once filled with oak pews and hymn books, the former chapel is now covered in clocks of all kinds, watchmaker repair kits, maps, toys, and record players. Allan guides visitors through while maintaining a leisurely pace so visitors can choose their own path. His animated hand gestures add a fresh feel to the proficiency that comes with more than two decades of museum experience. On work days, he wakes up around 7 a.m. to catch the news, then heads for the museum. Days are filled with guiding tour groups, conducting clock appraisals, and dealing with correspondence.

His dedication, which included working through the recent Easter weekend, has been recognized by the Ontario Historical Society. In 2019, the non-profit group presented him with the President’s Award, an honour bestowed on him the year before that recognizes outstanding contributions to the preservation of the province’s history.

“Allan Symons has done outstanding work collecting, researching, curating, and displaying clocks manufactured in Canada, most of them made here in Ontario,” the historical society wrote in a news release at the time. “As Canada’s only clock museum, it has brought national and international recognition to the history of Canadian clock-making.”

With the continuing hunt for the pink Snider Spider and other clocks waiting to be discovered, the museum’s collection will continue to expand — at least as long as its proprietor sticks around. With Allan approaching 80, Gary wonders if the unique collection’s time is winding down.

“The shame of it is that when Allan retires, the museum will probably disappear and the contents split up and distributed to museums across the province,” he said.

For now, though, Allan is happy spending his time touring and educating anyone wanting to listen.

“When people are leaving, absentmindedly they say, ‘Thanks for your time.’” he said. And his reply is almost always the same: “‘Was that pun intended?’”

***

Since April 2, 2021, the Canadian Clock Museum has been closed to the public to adhere to COVID-19 restrictions in Ontario.