By Soofia Omari

It’s 5 P.M on a Wednesday and the sound of silence is all that can be heard at Frontlines. This time last year, scenes of lively children rushing inside with their snow-covered boots were commonplace, but today, the once-bustling compound is kept alive by only a few beaming lights.

This is what the coronavirus pandemic has done to Frontlines.

Frontlines is a community centre for under-resourced local youth living on Weston Road, a low-income neighbourhood in the city’s west end. Established in September of 1987, their aim is to offer kids a safe place away from the streets and address their “physical, emotional and intellectual needs,” according to their website.

Latisha Taylor, the children’s program coordinator at Frontlines has been working at the centre since September 2018. The Humber college alumni who studied child and youth care always knew she wanted to work with children one day, maybe as a teacher, but once she met a CYC worker in high school, she knew this was her calling in life.

“I always make this joke like, I was born an auntie!” Taylor recalled.

“My siblings all have kids and I was always the one babysitting.”

Latisha Taylor. Photo via Weston Frontlines Centre/Facebook

On her first day, Taylor woke up eager to begin her student placement at Frontlines. She attempted to dress as professionally as an 18-year-old can settling on jeans and a light sweater that complemented the early autumn weather. As she entered Frontlines through their slate-blue coloured doors, Taylor was filled with anxiety. She worried about making the right first impression on her prospective future employers but once she met the kids, her fears dissipated. She knew she was the one for the job.

Fast-forward to 2020, Taylor is no longer able to see the kids that made her fall in love with her job. Due to new COVID-19 restrictions, all programs offered at Frontlines such as tutoring, French help, and the youth employment program have been moved to an online format.

“I used to go and see the kids basically five days a week in-person, you get to run around with them, playing games, draw, paint, and now it’s really hard to see all of them,” said Taylor.

Tobias Ramage, a program coordinator began his career at Frontlines in October of 2020, just as the province began to re-implement modified stage 2 COVID restrictions that limit on-site programming at community centres.

Sitting slouched over his laptop inside of his home which doubles as his place of work these days, Ramage explained that although online programming is going well, it still misses some aspects in-person programs would have had.

“You’re missing that social interaction aspect. Nothing beats face-to-face interaction. It’s just the way humans are, we’re social creatures,” said Ramage.

“It’s interesting building relationships via zoom, rather than in person because then you could really gauge like mannerisms and just where we might be able to help more. It’s just very different to interact in this way.”

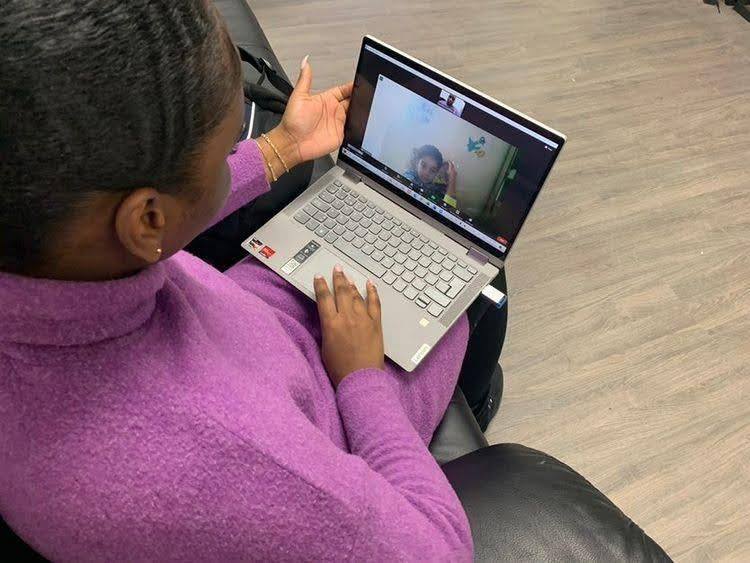

Staff at Frontlines tutors youth through Zoom. Photo via Weston Frontlines Centre/Facebook

While running summer camp at Frontlines, Taylor received criticism on the portions of camp that were online from some of the children.

“They told us, Latisha we’re not coming in, they’re like we don’t like it.”

French tutor coordinator at Frontlines Lea Muamba says it’s difficult engaging with the kids for this reason.

“I don’t know how many students are enjoying doing online school, talk much less of tutoring.”

Lisa Miles, guardian of a child at Frontlines says her grandson who once loved in-person programs stopped attending due to the online format.

“It’s almost impossible to get him to do online schooling,” said Miles.

“He would put up way too much of a fight.”

The loss of in-person interaction and dislike of the online format are just two ways Frontlines youth are being affected by the pandemic.

According to a study led by SickKids hospital published in February 2021, about 70 per cent of Ontarian children aged six to 18 years old experienced harm to their mental health during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“When we asked them, in the beginning, how do you guys feel and what do you know about it? (COVID-19) Some were telling us they were scared” said Taylor. “They didn’t really know what to do about it.”

In an effort to help children deal with the effects of the pandemic on mental health, the centre runs the “what’s on my plate” program, a creative way to combat mental health struggles.

The program is geared towards dealing with mental health by using food inspired by feelings. Program attendees talk about mental health disorders while they learn to cook a new meal each week.

“So, let’s say if it’s stress, then we would have a stress-inspired meal,” said Ramage.

Smoothies and schizophrenia, pancakes and boosting your self-esteem, and potato omelettes and social anxiety are just some of the topics and dishes that have been covered by the program.

A what’s on my plate program session on Zoom. Photo via Weston Frontlines Centre/Facebook

The centre has also recently added a new call line for anyone that needs support or if they just need someone to talk to. Taylor as well as other staff even keep their office open to any youth who need to come by to talk as long as they call ahead.

A few children at Frontlines additionally had to deal with inaccess to strong Wi-Fi and computers, a problem that meant they were unable to participate in online programs.

According to a report done by Social Planning Toronto in 2017, nearly 40 per cent of children living on Weston Road live in poverty.

After staff picked up on this issue, three youths were provided with free internet over the summer and 10 laptops were provided in September thanks to donations made to Frontlines.

Child holds tablet donated to him by Frontlines. Photo via Weston Frontlines Centre/Facebook

Although online programming has its cons, it also has advantages. Programs run by the centre were previously limited to kids living in the Weston area but online programming allows for children from all over Ontario to attend.

“I have kids that are like in the Niagara area, that are in like Windsor. We have some in Scarborough, we have some in Waterloo. So we had a lot of kids from a lot of places join,” said Taylor.

Their usual target of 60 kids for their after-school program has been surpassed due to online programming.

In addition to the online programs, Frontlines is also making an effort to continue to give back to the community—a mission they started 34 years ago. The centre gives out free groceries, meals, masks, and other safety supplies to members of the community every Monday and Thursday.

“We are doing our best as an organization to always consider the community that we’re serving,” said Ramage.

Taylor hands groceries to a community member. Photo via Weston Frontlines Centre/Facebook

Miles who lives across the street from Frontlines says the centre has helped her out on multiple occasions.

Around two months ago, Miles bought her groceries online but they never ended up arriving. Without her groceries, she didn’t even have enough food to make lunch so she contacted Taylor at Frontlines and explained her situation. Without hesitation, Taylor arranged for someone to give her groceries the next day.

“They made sure I didn’t go without anything, I even said it’s way too much! I just needed enough to get me through for a few days,” said Miles.

“They go the extra mile.”

Without any inkling of when in-person programming will resume, the centre and the community will have to deal with the difficulties of online programming indefinitely.

Those from the community have faith that when in-person programming finally does resume, Frontlines will do everything in their power to keep the children happy and healthy.

“They’re very cautious and very attentive to the kids. Even during COVID when he [her grandson] went in a few times, they only let five children in max,” said Miles.

As Ramage made his final remarks, he stared at the screen intently. Armed with enough thermometers, sanitizer and masks for everyone, he aimed to make it clear that the moment Frontlines is able to resume in-person programming, there is no doubt that they will be prepared and ready.