By Diane Hatheway

When Christopher Nkambwe arrived in Toronto from Uganda in 2019, everything felt like a challenge to overcome. Finding a place to stay and legal aid was difficult. Getting around the crowded streets of the city was hard as public transit prioritized the use of Presto cards, something Nkambwe didn’t know how to get. On top of it all, she had no idea where to meet other members of the LGBTQ community. Living in the city was tough, but Nkambwe knew it was where she needed to be.

“I have been free to do what pleases me in Toronto compared to when I was in Uganda where you are not free to be who you are,” she said.

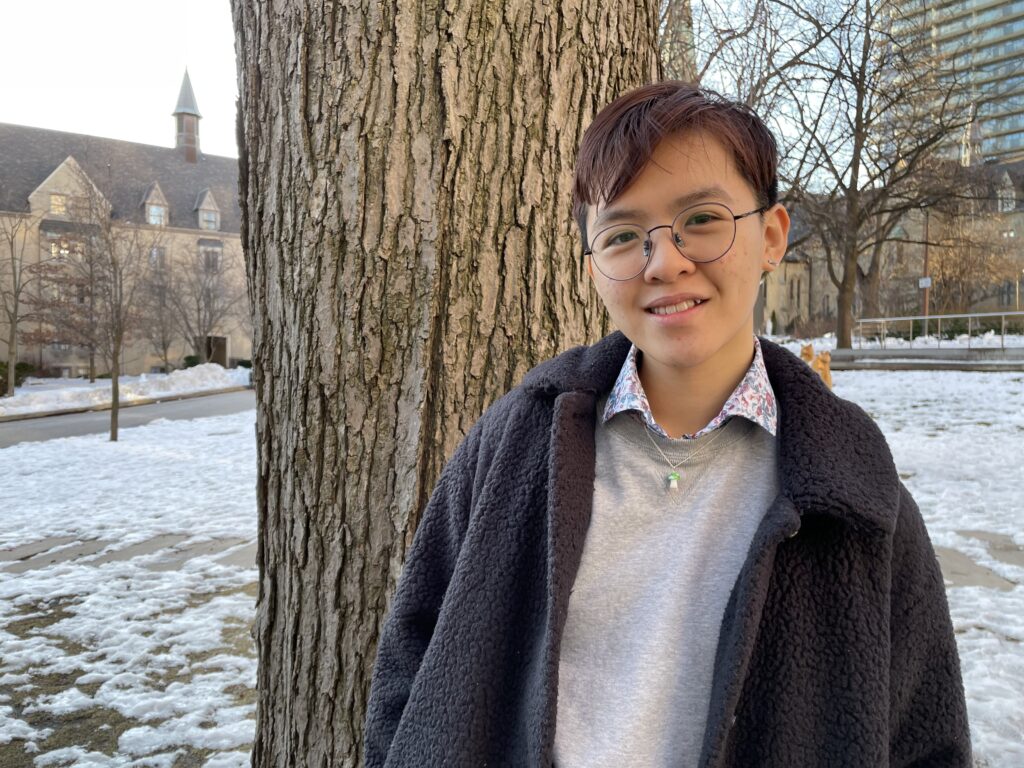

Nkambwe claimed refugee status in Canada because in Uganda she was wanted for being a trans woman. Without help, Nkambwe wondered how many other queer newcomers have gone through the same challenges as her. She knew things needed to change for other queer newcomers, and she wanted to be the reason it changed. It led her to create The African Centre for Refugees in Ontario-Canada later in 2019.

Last year, Canada welcomed almost half a million permanent residents. Thanks to Canada’s legal protection of LGBTQ individuals, it’s become a safe haven for people fleeing countries where being gay or trans is unsafe or punishable by law, but also for people looking to live their authentic queer lives. While up to date numbers are difficult to find, research done by Sean Rehaag shows The Refugee Protection Division (RPD) of The Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada reports from 2013 to 2015, 2,234 refugee claims were considered on the basis of sexual orientation. 1,575 of those claims were accepted.

Many organizations in Toronto help LGBTQ refugees set up a new life, such as Rainbow Railroad or The 519. For queer refugees from Africa, The African Centre for Refugees in Ontario-Canada provides legal aid, doctors, and other resources that will allow them to adjust and thrive in Canada. The centre also helps these newcomers find the LGBTQ community in Toronto.

When Nkambwe lived in Uganda, she worked as a human rights defender and sat on the organizing committee for Pride Uganda, until 2016, when an event they hosted was raided by police. In Uganda, homosexuality is punishable with ten years in prison or a lifelong sentence. After her name was put on a wanted list for “promoting homosexuality,” she knew she needed to leave. On the run from authorities, Nkambwe got a visa and a flight to Canada in hopes of escaping unfair persecution. Canada granted her refugee status in the country. The obstacles she faced in setting up her new life, and her previous activism, led to the creation of The African Centre for Refugees in Ontario-Canada.

“When I came to Canada, it didn’t mean that my activism work should stop just because I’m in a country that protects me,” Nkambwe said. “There is a gap missing, you know, that has to be filled.”

Others who have come to Toronto have found it offers a chance to be openly queer in addition to legal protection. Micah Tan, a trans masculine University of Toronto student from Malaysia, found that living in Toronto allowed him to explore his sexual and gender identity more openly. He was 13 when he attended a boarding school in Singapore. He came out to his friends when he was 17 while studying there. In Singapore, being openly gay or trans is taboo, and the country has only just repealed a law that criminalized sex between men. His friends were supportive of his identity, but the Catholic community he had grown up in and who supported him studying in Singapore was not. He knew this before he came out. It hurt him to see the community turn on queer people.

“It’s just hard.. especially when I first went to Singapore, it was the religious community that really brought me there,” he said. “Because I was this thirteen year old kid in a new country, it kind of broke me a bit.”

He enrolled in a university in Toronto to speed up his family’s immigration process to Canada, but the opportunity to be openly queer is helpful for him.

“Coming to Toronto was like a big sign of safety for me, the first time I came here I realized I can actually be myself,” he said. “I do see medical transition as an actual option.”

In 2019, Nkambwe opened The African Centre for Refugees in Ontario-Canada completely out of her own pockets. She still funds the organization with money she earns as a cleaner, and the occasional money she earns from awards. In 2020, she received Community One Foundation’s Steinert & Ferreiro Award for her outstanding work for the LGBTQ community in Canada, and put the $10,000 prize towards the centre. The centre has over 1000 beneficiaries as of 2023.

The centre also advocates for those in countries where being queer is illegal by holding protests and conferences. On March 21, Uganda passed a bill that allows for harsher punishment of homosexual offences, such as life in prison or the death penalty. The centre immediately planned a protest to oppose this bill.

The centre will run two conventions later this year. These gatherings include The Africa Canada International Convention on Human Rights Promotion and The Annual International Conference for Newcomers in Canada.

Mona, a source who is remaining anonymous, and a bisexual Toronto Metropolitan University student, hopes things change where she is from. She was born in Malaysia, but moved to Qatar when she was six. In Qatar, homosexuality is punishable by law. She said in her secondary school, students tried to identify each other as gay by dressing in goth or alternative fashions, or by using rainbow emojis in their biographies on social media.

“There was a really big queer community, but everything was under wraps,” she said. “If the teachers knew, we would all be expelled.”

There are harsh repercussions if a child comes out to their parents in Qatar. Some parents try to dismiss their children by telling them their queerness is a phase. Other parents send their children to conversion therapy or force them into heterosexual marriages, said Mona.

In Toronto, Mona is able to be open about her identity beyond subtle clothing choices and social media posts.

Nkambwe hopes speaking out against homophobic and transphobic legislation can help countries where being queer is criminalized to change. On April 2, the centre joined other organizations, like The 519 and Rainbow Railroad, to protest against the newly passed 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Bill in Uganda.

The crowd of over 100 people marched in the street from Yonge-Dundas Square to Queen’s Park, shouting “LGBTQ rights matter.” One Love by Bob Marley and the Wailers played from an organizer’s speaker while protesters sang along. Pride flags, signs that read “Protect LGBTQ Ugandans,” and signs made by the centre before the protest were held by almost everyone. While the situation for the gathering was grim, people at the protest were smiling and supporting one another even if the bill didn’t directly impact them.“As we march today, we are not marching only for the LGBTQ people back home,” said Nkambwe. “We are marching for the rest of the LGBTQ people in countries where being homosexual is criminalized.”