By Brianna Bailey

I had never experienced true darkness like that before. When I close my eyes, everything appears dark, but while dining, there is no visible change when I blinked. While eating my meal, my body felt tense and scared of what I was about to face. The saying “the eye eats first” has an entirely new meaning after eating in the pitch black. Upon entering the dimly lit foyer, I had no idea what to expect from the “dining in the dark” experience. As we ventured into the dark dining room, our server’s confident navigation through the complete darkness left me in awe. “How does he do this daily?” I thought.

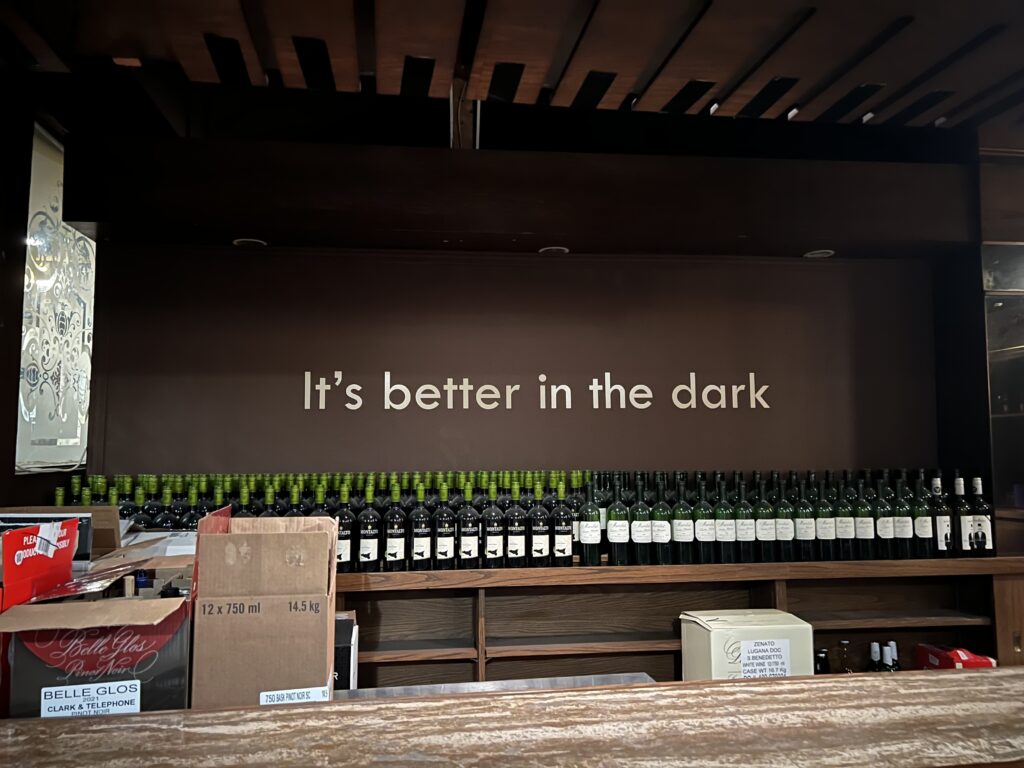

In the heart of Toronto’s bustling culinary scene lies O’Noir Toronto, a restaurant where patrons dine in complete darkness, immersing themselves in a unique sensory experience. O’Noir is part of a growing trend to employ people with disabilities in the restaurant world and in the process, challenge the low employment rates they face.

The restaurant, led by owner Dr. Jaren Feng, employs a completely blind waitstaff who navigate and serve the dining room. Feng shared that O’Noir Toronto works with organizations and aims to make a social change by hiring those with disabilities.

The current owner of O’Noir, Dr. Jaren R. Feng, is an entrepreneur, scientist and advocate for employing the visually impaired. Under Dr. Feng’s guidance since 2011, O’Noir Toronto has evolved into the world’s largest restaurant of its kind. “I think the most important thing is just to increase and promote awareness to the public,” Feng said. He said that O’Noir is beneficial to people who dine there because it allows patrons to block their sense of vision for a few hours. He explained that if you used to have five senses but now only have four, you will have gained a new appreciation for your vision.

One of the first ideas for a socially conscious workplace stemmed from Jorge Spielmann, a blind pastor in Zurich, who introduced the practice of blindfolding his dinner guests to allow them to experience eating as he did. Later, Spielmann launched Blindekuh (German for blind cow) in 1999 to educate the sighted about the world of the blind and create employment opportunities for visually impaired individuals. O’Noir Toronto opened in 2009, a few years after the Montreal location opened in 2006.

While Feng does not have a personal connection to the blind community, he says he is passionate about employing those who are visually impaired. Blind people do not need extensive training at work, as they already know how to navigate life without their vision.

Despite facing challenges associated with being blind, Dave Smith, a server at O’Noir, was enthusiastic about his job. Having lost his sight due to glaucoma at the age of 20, Smith has navigated the world with resilience for the past 22 years. His journey at O’Noir spans 14 years, during which he said he found fulfillment in his work and loves connecting with new people daily. For Smith and others like him, he said meaningful employment goes beyond mere job responsibilities; it represents a source of pride, independence, and purpose.

O’Noir has attracted patrons not only for its innovative dining concept but also for its impact on perceptions of disability. For dining guest Sissi Wang and her husband, it’s evident that O’Noir’s unique dining experience has left a lasting impression. “Not every visitor may find this restaurant appealing because it’s so different [than what we are used to], but I honestly think it made me reflect on the daily lives and challenges that blind people face,” Wang said.

Opportunities for individuals with disabilities have historically been limited, with statistics indicating a significant gap in employment rates compared to the general population. According to Statistics Canada, the employment rate among individuals with disabilities, at 73.9 per cent, stood notably lower by 14.5 percentage points compared to those without disabilities, whose employment rate was 88.4 per cent. The Ontario Disability Employment Network, states that despite efforts to promote inclusivity and accessibility, individuals with disabilities still face a lack of jobs available, accessibility, and discrimination when entering the workforce.

However, amidst this challenging backdrop, Feng mentioned that O’Noir Toronto’s initiative to hire only a blind waitstaff is an effort to address these disparities. Drawing inspiration from its counterpart in Montreal, O’Noir Toronto has embarked on a mission to provide meaningful employment opportunities for individuals with visual impairments. Mirroring the Quebec location, O’Noir Toronto has partnered with Horizon Travail, an organization affiliated with Emploi Quebec, to offer training and support for visually impaired individuals seeking employment.

Feng mentioned that O’Noir works with the The Canadian National Institution for the Blind (CNIB) and, before the COVID-19 pandemic, would often host fundraising events. “I think any awareness is wonderful, and we still do maybe 10 to 15 fundraising dinners each year about blindness,” Feng said.

The CNIB is a registered charity that offers community-based assistance, expertise, and advocacy, aiming to empower Canadians with blindness or partial sight to confidently engage in life with the necessary skills and opportunities. As per the CNIB, 1.5 million individuals in Canada self-identify as experiencing vision impairment, while approximately 5.59 million others may be at risk of vision loss due to eye diseases.

The CNIB, ODEN, etc., are among many organizations working towards employment for everyone. Sarang Kitchen is another example of commitment to inclusive hiring practices. Sarang Kitchen’s mission statement is to promote diversity and accessibility in the workplace, reflecting broader societal trends toward inclusivity and equal opportunities. Their mission is to eliminate employment obstacles faced by individuals in the neurodivergent community. As Toronto continues to embrace diversity and champion inclusive hiring practices, businesses like O’Noir Toronto and Sarang Kitchen are working towards access to meaningful employment for all individuals.

Despite the daily challenges of being blind, Smith and the rest of the waitstaff at O’Noir demonstrate skill and professionalism in serving their tables. While such endeavours are commendable, people with disabilities still face systemic challenges and biases that hinder their full participation in the workforce. Feng hopes that O’Noir can pave the way for disability employment and that everyone capable has the opportunity to work.