By Pauline Nasri

The clock strikes 12 p.m. and the lights of the “Open” sign flash on. The sun shines through the glass storefront of Zezafoun Syrian Cuisine. Traditional Arabic music, from Fairuz to Oum Kalthoum and Abdel Halim Hafez echoes in the background of Zezafoun, which some customers call “Little Syria.”Two Syrian women, Marcelle Aleid, and her mother Yolla Alwardi, who goes by Chef Yolla, are the owners of Zezafoun Syrian Cuisine. The restaurant opened in 2018 in midtown Toronto. It is the place in the city to discover the origins of the Syrian culture and food, according to Aleid.

The story of Zezfoun goes beyond the smell and sights of delicious food that greets anyone entering the restaurant. Most of the staff are immigrant women, a part of them to be found in everything at Zezafoun, whether in the art and decoration or the taste of the food. The restaurant is also a place for anyone yearning to feel a sense of community. Zezafoun wouldn’t be what it is without Chef Yolla’s cooking, Aleid’s leadership and the work of resilient immigrant staff.

The name Zezafoun is the Arabic word for linden trees, which cover the mountains between Lebanon and Syria. Their long branches and insect-repelling aroma have made them the ideal gathering place for many Syrians over the years to eat under, socialize, play music and dance.

Today, people can gather at Zezafoun Syrian Cuisine to connect, just like they used to under the linden trees years ago.

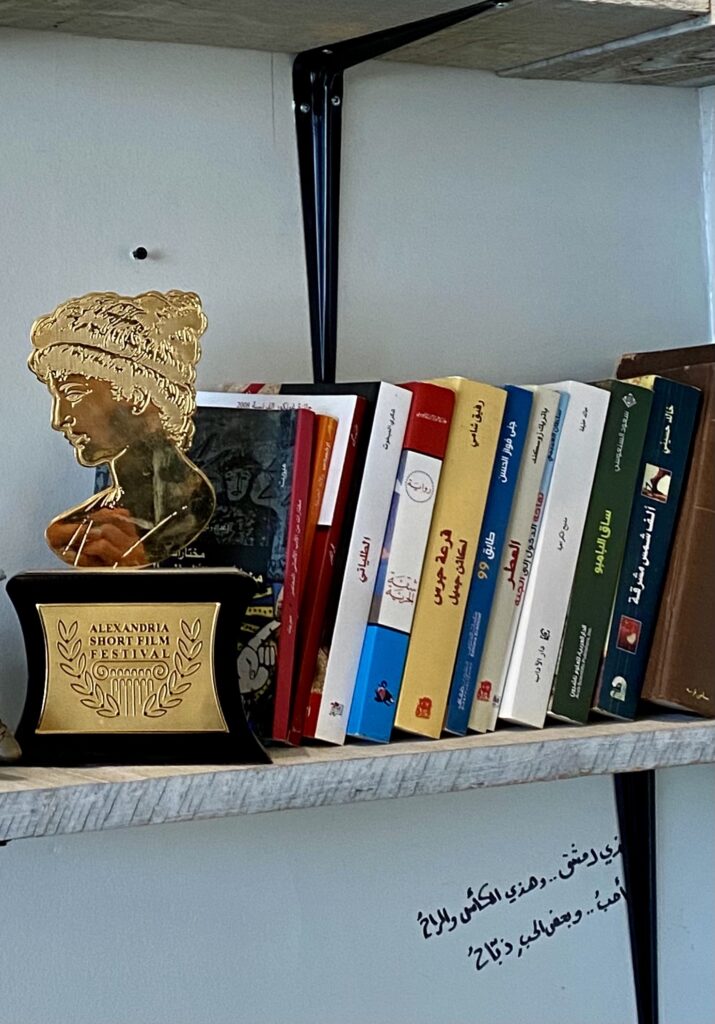

Aleid is a published writer and a film director. She has published, directed and written multiple award-winning films, including “The Truth” which won the Golden Hypatia Award at the Alexandria Short Film Festival and the Best Film award from the Egyptian Film Critics. She has also served as the project manager for launching the Arabic version of Sesame Street.

Chef Yolla was a music teacher for almost 30 years. After moving to Canada in 2014, she overcame the challenge of learning English and worked as a hairstylist for a couple of years.

Finding it difficult to establish themselves in their respective creative fields in Canada for lack of Canadian experience, Aleid and Chef Yolla said they took many risks launching themselves in the food industry with no prior experience. They learned food safety, the business of running a restaurant, and brought their experiences and talents in various fields to represent the Syrian culture and give back to the community through Zezafoun.

“We all have a background in the arts field … so we all cook in a spirit of art,” Chef Yolla said, in an interview conducted in Arabic.

This is Zezafoun Syrian Cuisine’s storefront, located in midtown Toronto, on March 13, 2021. The restaurant’s name is written in both Arabic and English on the signboard with diacritical marks which help people pronounce Arabic words correctly. (Pauline Nasri/T•)

This is Zezafoun Syrian Cuisine’s storefront, located in midtown Toronto, on March 13, 2021. The restaurant’s name is written in both Arabic and English on the signboard with diacritical marks which help people pronounce Arabic words correctly. (Pauline Nasri/T•) Lama Skaff (left), a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, helping a new staff member, Joudy Kusaibati (right), on March 13, 2021. (Pauline Nasri/T•)

Lama Skaff (left), a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, helping a new staff member, Joudy Kusaibati (right), on March 13, 2021. (Pauline Nasri/T•) Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, ordering from the chefs in the kitchen a Syrian traditional meal called “Burning Fingers,” on March 13, 2021.

Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, ordering from the chefs in the kitchen a Syrian traditional meal called “Burning Fingers,” on March 13, 2021.

(Pauline Nasri/T•) Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, sprinkling crispy onions on the cooked lentils plate, on March 13, 2021. Syrians use plenty of crispy onions in their meals since it adds texture and sweetness to the dish. (Pauline Nasri/T•)

Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, sprinkling crispy onions on the cooked lentils plate, on March 13, 2021. Syrians use plenty of crispy onions in their meals since it adds texture and sweetness to the dish. (Pauline Nasri/T•) Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, adding fresh cilantro beside the crispy onions, on March 13, 2021. For Skaff whenever she makes “Burning Fingers,” she is reminded of the food she grew up eating in Syria. (Pauline Nasri/T•)

Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, adding fresh cilantro beside the crispy onions, on March 13, 2021. For Skaff whenever she makes “Burning Fingers,” she is reminded of the food she grew up eating in Syria. (Pauline Nasri/T•) Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, taking a handful of crispy pita bread to pour it into the “Burning Fingers” plate, on March 13, 2021. The crispy pita bread adds a texture to the “Burning Fingers” dish. (Pauline Nasri/T•)

Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, taking a handful of crispy pita bread to pour it into the “Burning Fingers” plate, on March 13, 2021. The crispy pita bread adds a texture to the “Burning Fingers” dish. (Pauline Nasri/T•) Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, decorating the plate with pomegranate seeds before serving it on March 13, 2021. This is one of the dishes which remind Skaff of the Syrian cultural and traditional food. (Pauline Nasri/T•)

Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, decorating the plate with pomegranate seeds before serving it on March 13, 2021. This is one of the dishes which remind Skaff of the Syrian cultural and traditional food. (Pauline Nasri/T•) Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, closing the takeout box of the “Burning Fingers,” on March 13, 2021. She makes sure that it is well-packed to avoid spilling. (Pauline Nasri/T•)

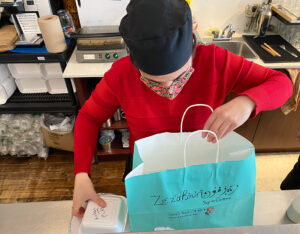

Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, closing the takeout box of the “Burning Fingers,” on March 13, 2021. She makes sure that it is well-packed to avoid spilling. (Pauline Nasri/T•) Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, putting the packed “Burning Fingers” box in Zezafoun’s handmade bag, on March 13, 2021. Three of Zezafoun’s staff members are architecture students, including Skaff, they bring their talents to draw and write on these bags. (Pauline Nasri/T•)

Lama Skaff, a Syrian staff member at Zezafoun, putting the packed “Burning Fingers” box in Zezafoun’s handmade bag, on March 13, 2021. Three of Zezafoun’s staff members are architecture students, including Skaff, they bring their talents to draw and write on these bags. (Pauline Nasri/T•)

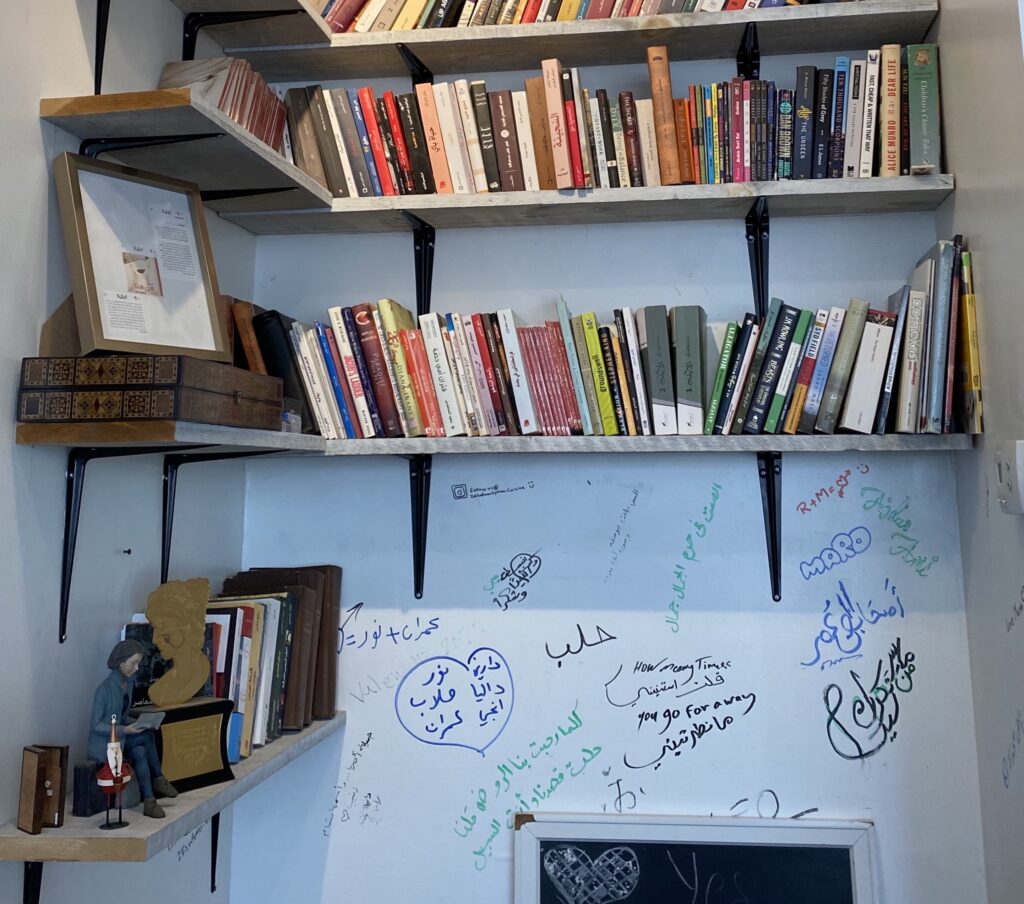

Music nights at Zezafoun bring chef Yolla’s food and live music together. Sometimes the band stands in the right corner beside a vintage glass cabinet, labeled “Dukan Zezafoun” which means “Zezafoun’s little shop” in Arabic. The Dukan has handmade embroideries, Arabic coffee pots and cups, mosaic boxes and other souvenirs, all from Old Damascus. On music nights some people take photos in a customized Instagram frame which says, “Selfies with Zezafoun” and a caption, “Share the love of food!”

Some music nights are Syrian folklore nights, when people dance with their hands flowing in the air in the same direction, singing loudly, clapping and drinking. There are patriotic songs that many Arabs learn in elementary school, including “Baktob Esmik Ya Bladi” meaning, “I write your name, my country.” The song begins with, “I write your name, my country, on the sun that doesn’t set.” The song goes on and the singer pauses and lets the audience sing all together, “la la la la.”

“Some customers would eat and leave the restaurant, as they cross the street, they come back saying, ‘we are sorry we forgot to pay, the place made us feel that we are at our parents’ house and we ate and forgot to pay,’” Chef Yolla said.

Pauline Nasri/T•

Learning a new language in a new country, being in the food industry for the first time, doing all the shopping and heavy lifting for supplies were only some of the challenges Aleid and Chef Yolla had to face.

“Carrying heavy stuff while climbing the stairs is physically exhausting for women. However, I learned how to carry heavy stuff without hurting my body,” Aleid said, in an interview conducted in Arabic.

Sally Dimachki, a Syrian immigrant and community mobilizer, said in a virtual interview that patriarchy has universal challenges, but also comes with challenges that are specific to each culture.

“When newcomer women start a business, they unlock opportunities for other newcomer women … And they know the specific challenges that other newcomers face, so they try to build that within their business and their opportunities,” Dimachki said.

Vanessa Bou-Chedid, a Lebanese staff member at Zezafoun, moved to Toronto in 2010 and started working at Zezafoun two years ago as her first job.

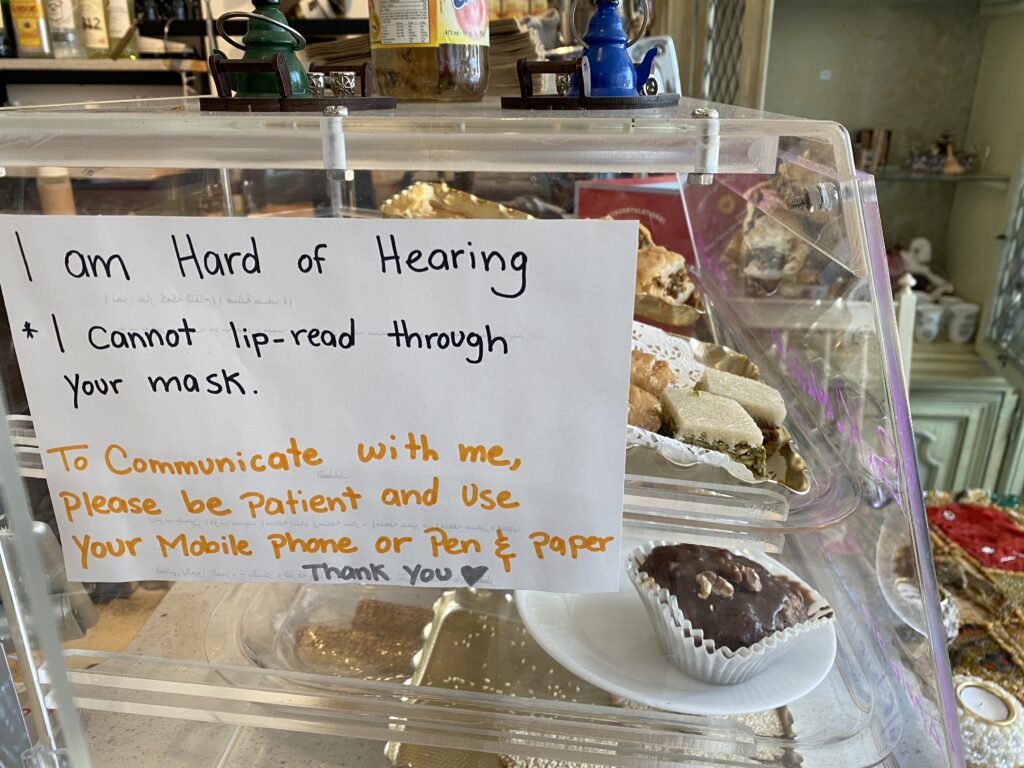

“I am glad they accepted and supported me, no matter what. I learn a lot and they help me improve. I also show them that I can do it even if I am a woman or hard of hearing,” she said.

Aleid is spotted during the week at Zezafoun with her red pixie haircut and her drop earrings.

“A woman needs to know that she is strong and that she is capable. She needs to know herself and what she exactly wants and have the ability to achieve her purpose using her mind, intelligence and inner strength,” Aleid said.