By Adriana Fiorante

Act 1: The intent to live

Inside a lilac-walled studio of blond wood flooring and no windows, Miriam Laurence saunters around in sunglasses and a faded noir baseball cap. An obnoxious buzz vibrates her North York studio and Laurence walks to the door, gently inquiring: “Yes … OK, come in.” Back into the studio, she pulls a wheeled desk toward the worn carpets that line the entrance of the cave. Two television screens stacked on top of each other and a nest of wires sit on the desk.

Laurence has been teaching acting for almost 30 years, one-on-one, on set, and in group classes.

Her skin is ironed smooth, her voice light as air. There is no clear mark of her age. Her eyes remain emotionally static as she scans the room. As she sets up, she meows and experiments bird-toned pitches with various vowel sounds.

When Laurence was 18, she studied acting in New York City with the legend who trained the likes of Pacino, De Niro, Newman and more – Lee Strasberg. Many of the exercises she uses in her acting class have been appropriated from what she learned in The Actors Studio – Song and Dance, Personal Moment, Object, Chair.

The students clamber in one by one at noon on Saturdays, Sundays and Mondays. The room changes from a desert to a thunderstorm as the students noisily prepare.“All right,” Laurence coos after 15 minutes of various lunges, twists, and vocal runs. “Make a circle.”

Ten students of different ages, hair colours, heights, shapes, sizes, silence their warm-up and form a circle, not unlike kindergarteners, connecting with a partner across them. In sync, they sing Twinkle Twinkle Little Star syllable by syllable to each other while thinking about anything other than the song.After everyone is warmed up, an assembly line of chairs forms and delivers everyone to a seat — with a metre of space on each side — throughout the room.

“Tense a muscle in one part of the body and when you release it, make a sound,” Laurence whispers to her focused audience. “Va-va-va-vaaaa,” as her thigh rises and falls in tension and relaxation.

A quarter of an hour later, the class is in a near-catatonic state as screaming erupts from one corner of the room, sighing and sloth-like movement another. The actors are contorting over their seats as Laurence slinks from one occupied chair to another, moulding her hands over their muscles to feel for tension.

To Lydia Cain, Laurence whispers, “You have to allow yourself to be louder.”

Cain slumps her head forward as Laurence guides her shoulders off the back of the chair. Cain’s head slowly drops to the seat of the chair in between her out-stretched legs. Laurence’s palms mould over Cain’s curved spine, coaxing from Cain a gentle “ahhhh” as Laurence applies therapeutic pressure.“Al Pacino said ‘hi’ to me once,” Laurence encourages in a mothering tone. “And I was too nervous to say anything back. My whole life could have been different.”

Act 2: A dream of passion

The Taming of The Shrew’s Petruchio lives in the untoned body of Farbod Pakpour, who is shifting from left to right before the starting pistol of Laurence’s “begin.” Petruchio is adorned in a lazy Sunday outfit: grey slacks, nondescript loose grey shirt and slippers.

A civil engineer by trade and an actor by passion, though wrinkles around his walnut-coloured eyes have grown deep, they are youthful still. His Persian tongue mangles W’s and R’s unlike a native English speaker, a bit punishing on his consonants, rolling his Rs.

“Now … by the world,” proclaims Petruchio with gusto. “It is a lusty wench!”

Though Shakespearean is unnatural to Pakpour — whose first language was Farsi, then French, then English – it sounds as though he is saying it from the soul, not the mind.

“I love her ten times more than I e’er did,” his lips part and from the jungle of hair a smile emerges. “Oh,” a long pause, his eyes glow. “How I long to have some chat with her!”

“It’s really coming along,” Laurence praises. He has been a student of Laurence’s for years. “Such an improvement from how you were when you started! I can’t wait for you to be able to finish your studies and act full-time. How much longer will your PhD take?”

“I don’t know,” Pakpour’s eyes gloss. He flops his head to the side. The jovial Petruchio has vanished, it is a wonder how Pakpour found the light in this dark cloud. “I have no idea when it will end. My boss is very intimidating, he is always yelling, and I am not getting paid. Otherwise, I would be committing to acting full-time.”

“I’m sorry,” Laurence reassures.

While Petruchio’s voice was strong, vibrant, confident and resilient, Pakpour’s now is broken in half.

“It is like you are a slave. It is literally like you are a slave.”

Act 3: An actor prepares

Pedro Abrantes’ head, crowned by a receding hairline, is almost making contact with his knees. He contorts himself in the corner of the lilac studio while contributing to the pre-class discussion, albeit not one that many would feel immediately comfortable joining. Most involved in the discussion speak in ogre-tones and extended vowels. “Nobody in C-C-C-Canada knowowowows how toooooo drive,” his words are ushered by a Portuguese inflection and framed by thick lips. “Back hooooooooome, everyone is a precaaaaaautious and proactiiiiiiive driver.”

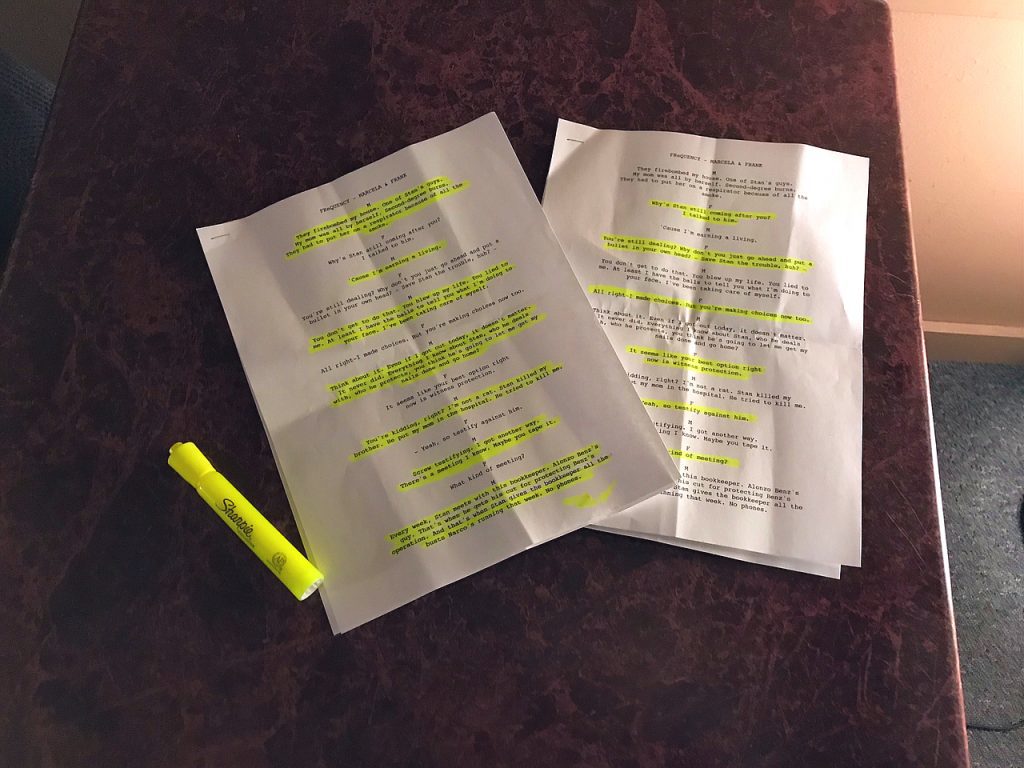

Laurence expands the legs of a tripod, topped by a 10-year-old video camera, and rearranges a web of wires into one long rope connecting to one of the televisions. Three other students in the class morph into the crew and move the stage lights a foot here and an inch there at Laurence’s direction.

While the set is being struck, Abrantes sits on a grey chair and opens his mouth as wide as he can, stretching his tongue to chin. He punches the air with fury, his face contorted in the manner of the Cheshire cat.

His face beams through the television, his shoulder (a reader to whom he speaks his lines) sits to the left of the camera.

Laurence presses the red button on the camera, and eases back into her chair. “When you’re ready,” she susurrates, with such softness it is almost silent.

Abrantes lifts his head, the words are no longer from the pages of Mamet’s The Verdict, but his gut. His lips shake on notes of passion, his hands fly as he speaks of justice being lost in America.

What did he say? What does he mean? His Portuguese pronunciation, while beautiful, makes it hard to hear the nuances.

There is a beat when he finishes and Laurence hops to constructive criticism: “Good, now do you want to work on your accent?”

“Yes, if David (the shoulder) can correct me throughout?”

The shoulder nods.

The now-familiar words, facial expressions, and gestures are repeated, but this time the shoulder repeats the words Abrantes pronounces too hard on the R, too cushy on the S.

The look in Abrantes’ eye is no longer full of anger and passion, but deadened, focusing on the forward movement of the shoulder’s Canadian inflection.

“My accent has gotten in the way, it will be hard for me to get roles here. It’s very hard to grasp English fully.”

Abrantes announces after that he has landed a good agent in Toronto. After a year and a half of classes and many Portuguese short films, it is a step toward his dream.

He offers a second “thank you” to the shoulder as he leaves, the shoulder refuses thanks, and compliments Abrantes’ improvement over the last few weeks.

While saying her goodbyes to the Saturday class, Laurence packs up her tripod. Tomorrow, a whole other group of students will simulate the same dance as today’s class, immersing themselves in similar chaos and growth.