By Julia Gianfelice

Rob Stonehouse takes one look at his shelf and immediately reaches for a book. Holding the hardcover, he can’t help but smile at his unique find.

In his hands is a first edition copy of The Cuckoo’s Egg, an account of the hunt for a computer hacker. For Stonehouse, who works in information security, this book is the “Ark of the Covenant.”

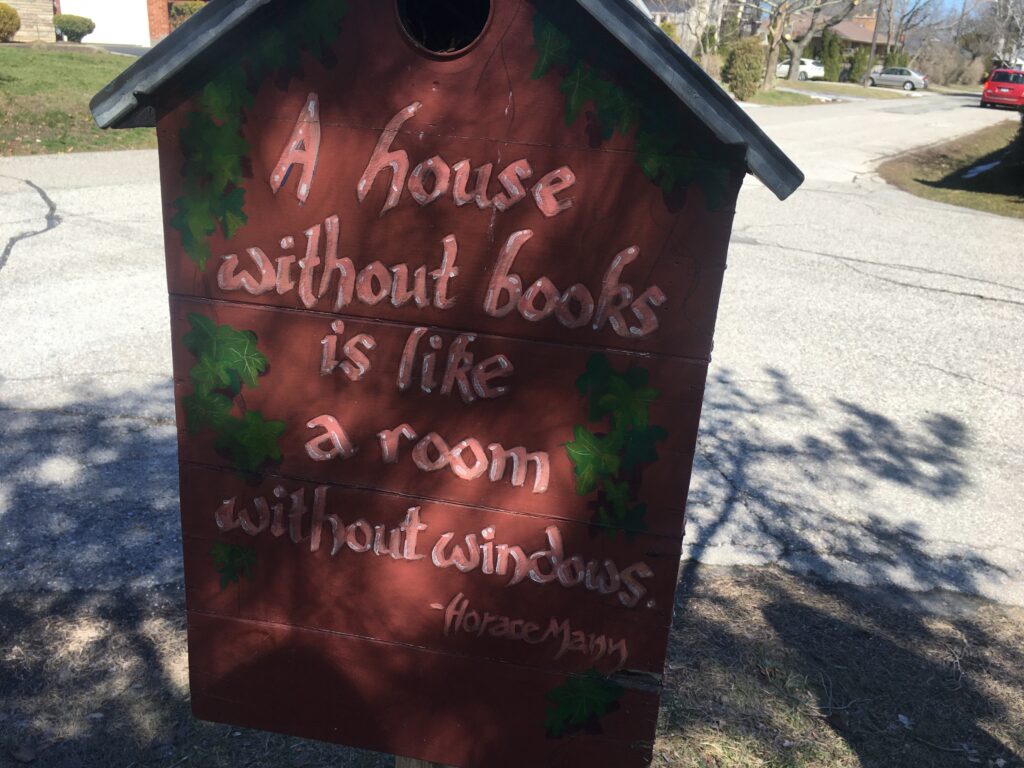

Stonehouse discovered the book in his Little Free Library, a small wooden box with free books located outside his home in Etobicoke. Sitting on top of a wooden pole is a red two-storey house, roughly the size of a large birdhouse. Stonehouse’s collection of 20 to 30 books come from community members who drop off a story or pick one up free of charge. His library, like others, is open 24-7, doesn’t require a card and has no late fees.

“It’s kind of like the surprise box at the fair. You don’t really know what you’re gonna get, as opposed to, if you’re going to a library, you’re looking for something and you’ve got a wide range,” said Stonehouse. “So I think it’s luck of the draw.”

Little Libraries, like Stonehouse’s, provide more than just free books: They have more notably become gathering places to meet neighbours and build community. During the COVID-19 pandemic, people had limited access to public libraries due to social distancing precautions and relied on Little Free Libraries for books and social connection. Yet, critics argue that Little Libraries do not create community and are instead depots for garbage novels. They also tend to be more common in affluent areas, which goes against the movement to promote reading in high-need communities.

In 2009, Todd H. Bol created the first Little Free Library box at his home in Wisconsin with a vision of a book for every reader and a Little Library on every block. The book exchanges became a global phenomenon, and today there are over 150,000 Little Libraries in more than 115 countries.

The first Little Free Library came to Toronto more than a decade ago, and there are now more than 150 in the city, according to the organization’s online map. However, the number could be higher because not everyone who sets up a library registers it with the group, as there is a fee of $40.

Little Free Libraries’ mission is to be a catalyst for inspiring readers, building community and expanding book access. They accomplish this through programs such as their Read in Colour initiative, which has distributed over 40,000 books celebrating BIPOC, LGBTQ+ and other marginalized voices.

Yet, some believe Little Free Libraries are useless and don’t create a sense of community.

Danielle Miriam Cooper, a librarian and director of libraries, scholarly communication and museums at Ithaka S+R, an education research organization based in New York City, says Little Libraries are about individual homeowners who want cool things on their lawns. She argues that these libraries don’t provide anything beneficial for the community.

“All they’re doing is being a depot for trash exchange that happens to be in the form of a book,” said Cooper.

According to the Journal of Radical Librarianship, Little Libraries appeal to the privileged, as they are generally located in highly educated communities that have easy access to public libraries. The article notes that the majority of Little Libraries in Toronto are in medium to high-income neighbourhoods, which goes against the organization’s mission to enhance literacy in high-need communities.

Within Etobicoke itself, this becomes clear. In 2016, the median household income for Stonegate-Queensway was $85,000, according to a City of Toronto profile, based on census data from Statistics Canada. The affluent neighbourhood has nine Little Libraries. By contrast Mimico-Queensway has a median household income of $68,000, and only two Little Libraries.

Advocates hope that as Little Free Libraries become more popular, community groups will set them up in neighbourhoods where they could do the most good. For instance, many Little Libraries, like Stonehouse’s, hold copies of shortlisted novels for the prestigious Scotiabank Giller Prize. According to Scotiabank’s website, the collaboration between the bank and Little Free Library provides “more Canadians access to the Prize’s shortlisted novels, and promote[s] the work of some of Canada’s most talented and diverse authors.”

Vilma Stanko, an Etobicoke community member, says she’s drawn to the colourful book exchange boxes because of the variety of novels they offer.

“It’s very intriguing to open up the door and see what’s inside,” said Stanko. “Because I love to read, I notice all kinds of books in there and it’s fascinating to see what other people are reading.”

Stonehouse’s Little Library serves as a destination for people when they walk and has also become a conversation starter for neighbours who might otherwise go years without meeting. Some neighbours who want to meet Stonehouse come up to his front door to offer up books that won’t fit in his library. Other times, a simple wave is enough to begin a chat. Stonehouse recalled a day when a group of eight or so teenagers surrounded his Little Library. Some rifled through the box for a book and Stonehouse asked if they had found something they liked. Their response: “Well, we’re here for the Pokémon.”

Stonehouse says his Little Library has been a good way to meet people, especially when moving to a new neighbourhood six years ago. “I would do it again,” he said. “It’s been a real positive experience.”