By Kahfeel Buchanan

Even though people walking by the Village Players aren’t always sure this basement theatre is still open, a community group has performed plays here since 1977.

Past a shawarma spot, a couple cake shops and a pasta cafe along Bloor Street West, there’s a sign above a basement space that reads “Theatre.” There are no lights and nothing to indicate whether it’s open, other than a poster in the window advertising the coming attraction – an image of a man and boy silhouetted against a beige farmyard.

Walking by, you might assume the theatre has been closed for years, and if you ventured down the two flights concrete stops to the glass entry doors, you’d find them ashy. But, in fact, this basement is the home of an active community theatre group called the Village Players, who’ve parted the playhouse curtains to tell more than 150 stories over the years.

As she takes me on a tour of the theatre’s interior, past its 160 seats with wooden armrests awaiting the next audience, Anne Harper, the group’s president, is reminiscing about 20 years of producing, directing, and acting with the Village Players.

Harper’s love of theatre goes back to her childhood. As a young girl, she performed plays with her Sunday school group in London, England, and when she moved to Canada about 40 years ago, she joined her first community theatre group here as a way to find people she could relate to and who shared similar interests. Eventually, she hooked up with the Village Players because her old group decided they were transitioning strictly to slapstick comedy plays.

Why do people join community theatre?

“It’s a great social activity, if nothing else. If you even thought you’d like to be creative in some way, you’ve got that opportunity [here],” Harper said.

Many of the group’s members tell a similar story. In different ways, the Village Players fills a void in their lives.

David Nicholson was divorced and looking for something to do when he heard about the opportunity to shine lights on the Village Playhouse stage, about 20 years ago.

“It’s got life as an organization. Those of us who are on the board [of directors] now, several of us have been there for at least the better part of 20 years,” Nicholson said, during a phone call.

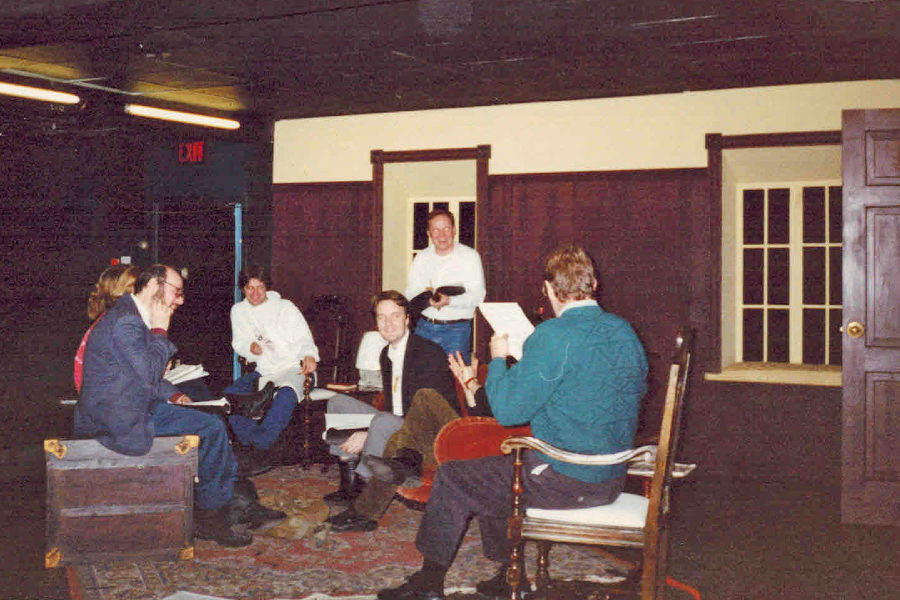

The Village Players rehearsing for a play in March of 1994.

The Village Players rehearsing Maggie’s Getting Married, a comedy, on April 21, 2015.

Nicholson says the group doesn’t advertise much. Potential volunteers usually hear about the Village Players through members in the group.

Nina, who last volunteered in March, assumed the doors were slammed shut before she volunteered to deal brochures out and inspect tickets at the playhouse. Last February, a member of the Village Players strolled into her yoga class, a studio perched above the playhouse; the woman was trying to fill the spots of group members who bailed on an upcoming show.

Nina, before she volunteered, thought “for the longest time, they were closed, because who keeps a small community playhouse alive?”

The Village Players are one of 35 groups part of the Association of Community Theatres Central Ontario (ACT-CO), the official organization for GTA community theatre groups.

Nicholson says they fumble lines for months and drip their sweat on stage because “it’s a way they like to spend their free time, and if it’s not fun, they’re not going to keep doing it.”

Some actors and theatre school graduates link up with the Village Players to add another page to their resume.

“In community theatre maybe they can get a lead role. They get bit parts in the real world,” Nicholson said.

How is everything paid for?

The group’s secretary, Theresa Arneaud, says the theatre company doesn’t make a profit , “we just make enough to support ourselves”. At five plays a year, they can make enough money to keep the lights on. Everyone, except the person picking up garbage left under seats, is working for free.

The company pays for rent and show production by fundraising, selling single show tickets, and selling subscriptions.

“We have just under 900 subscribers,” Nicholson said.

Subscribers receive discounts on tickets in exchange for a three, four- or five-show commitment. Adult single ticket buyers pay $24 per show, while subscribers pay $95 for a five-play subscription and save $25.

“Our average subscribers have come for 10 years. The subscribers tend to be an older group, 60 and up. Single ticket buyers seem to be on the younger scale. Historically, people bought subscriptions to theatre – when I was growing up that was the thing,” Nicholson said.

A 63-year-old woman from the neighbourhood, Anna James, told me she and her husband were pleasantly surprised when they stumbled into the basement theatre for the first time, a year and a half ago.

“We’ve been a couple times in the last 18 months. They’re actual semi-professional actors; it’s actually higher quality than you would think. I could see that it was local people that were there, so I enjoyed that. It was also unique for me because you could feel the subway rumbling underneath during the performance.”