By Emma Sandri

It’s an unmistakable sound. A loud gurgling, almost like a snore. The body goes limp, the head slouches over and the fingertips become blue. Then, a loss of a life, the sound of a siren, a tearful phone call.

This is what the opioid crisis looks like, but most Torontonians will never see it. It’s unlikely they will witness an overdose in public, or see someone using as they walk down the streets. They won’t be able to see that dozens of people have died this year, perhaps in their area. Yet, the crisis is there, lurking behind the pain people carry.

“I see a lot of really upset and sad community members and friends [In Bloor-Ossington] who are experiencing overdoses, who have family members and friends who are experiencing overdoses,” says Alannah Fricker, a harm reduction advocate, who lives at the edge of Dufferin Grove. “So I see a lot of sadness.” Fricker has seen what the opioid epidemic looks like first hand—on the subway, via people’s Facebook posts from her friends and in the trauma of her community. As a third year social work student at Ryerson University, Fricker has tried to bring harm reduction services and supports to students on-campus through the Ryerson chapter of Canadian Students for Sensible Drug Policy (CSSDP Ryerson).

Currently, the provincial and municipal levels of government in Ontario have introduced policies meant to curb harm associated with substance use, including the installation of supervised consumption sites for users. Yet, while politicians in Queen’s Park debate what’s best for the province, advocates work on-the-ground, raising awareness, education and funds for harm reduction strategies in the context of the epidemic.

As the opioid crisis rages on, the need for concrete solutions to overdose deaths becomes more apparent. From January 7 to March 18, 2019, there have been 44 fatal overdose calls to Toronto Paramedic Services, according to the city of Toronto. While the numbers are jarring, they represent a small fraction of overdose deaths in the past four years. In 2017, the city reported that there had been a 125 per cent increase in opioid related deaths since 2015, with over 300 people in the city having a fatal overdose.

Fricker knows that students are using substances, she’s heard about it first-hand. In a cramped corner of a coffee shop, she sits at the table, a furrow in her brow. While she does not like to start the conversation around harm reduction with her own personal experiences, Fricker feels that there is an importance in humanizing the way we think and look at drug addiction. “There are people in my life, who I love, who have experienced homelessness, who have experiences with sex work, drug use, overdoses, addiction,” she says, her triangle-shaped earring jostling. A fast-talking and passionate speaker, Fricker’s fingers clasp a cup of tea, as the hissing sound of the coffee machine interrupts her speech.

The CSSDP Ryerson, founded by Fricker in 2018, has been active in promoting harm reduction strategies. In the past year, they have put on information sessions, held panel discussions, advertised tours of the supervised injection site next to Ryerson and even sold t-shirts on the topic. “Decriminalizing and legalizing drugs is not something that I can do, this is a bigger structural transformation. But the idea of harm reduction is almost getting us to that point,” she says.

“A philosophy that supports self-determination, human rights, people’s autonomy.”

– Alannah Fricker

Despite being associated with substance-use practises, all people engage in harm reduction in one form of another, she says. Whether it’s putting on a seatbelt or limiting caffeine intake, everyone seeks to mitigate the negative impacts of daily life. “It’s a philosophy that supports self-determination, human rights, people’s autonomy,” adds Fricker, her restless hands moving through the air. “It becomes more of a political statement when it’s substances that are highly stigmatized.”

It’s this lack of education surrounding harm reduction that she says briefly hindered her work at the university. Following her founding of Ryerson’s chapter of CSSDP, Fricker applied for official student group status from the Ryerson Students’ Union (RSU) and was originally denied. She explains that she didn’t think that the decision would be controversial, as harm reduction has become increasingly mainstream. The whole point of the Ryerson chapter is “humanizing people who use substances, empowering folks and supporting their dignity, in whatever their healing process is,” says Fricker.

When the CSSDP at Ryerson first began, the group had no funding and no operating budget, says Olson Crow, the vice-president equity of the chapter. All expenses at the time were picked up by Fricker, who paid out-of-pocket simply because “she cares so much about this work,” Crow adds.

Crow has been involved with the group since its inception, when Fricker reached out to him and asked for help in starting the CSSDP. He had been a part of the RSU as the vice-president equity in 2017-18, where he advocated for staff to be trained in the use of naloxone, an opioid reversing medication. “Everyone uses drugs. It’s important that we de-stigmatize the idea of who is and who isn’t a drug user.”

Since its founding in 2018, Crow notes the group’s success at Ryerson has a lot to do with Fricker’s never-ending hard work. His voice, measured and even over-the-phone, breaks into laughter as he describes the 20-plus page research paper Fricker once prepared about harm reduction on campus.

“It’s important that we de-stigmatize the idea of who is and who isn’t a drug user”

– Olson Crow

Yet while Fricker’s drive is apparent in the success of the Ryerson chapter of CSSDP, the Dufferin Grove resident has not always been a vocal advocate. Previously, Fricker was enrolled at OCAD for illustration and then at Ryerson for psychology. It was during her “third attempt at a degree” that she became interested in harm reduction. She cites the lack of support for students using substances at Ryerson as the reason for which she started the CSSDP. “There’s also no harm reduction course, there’s no harm reduction electives at the school. As a school focused on social justice, I found it pretty appalling.”

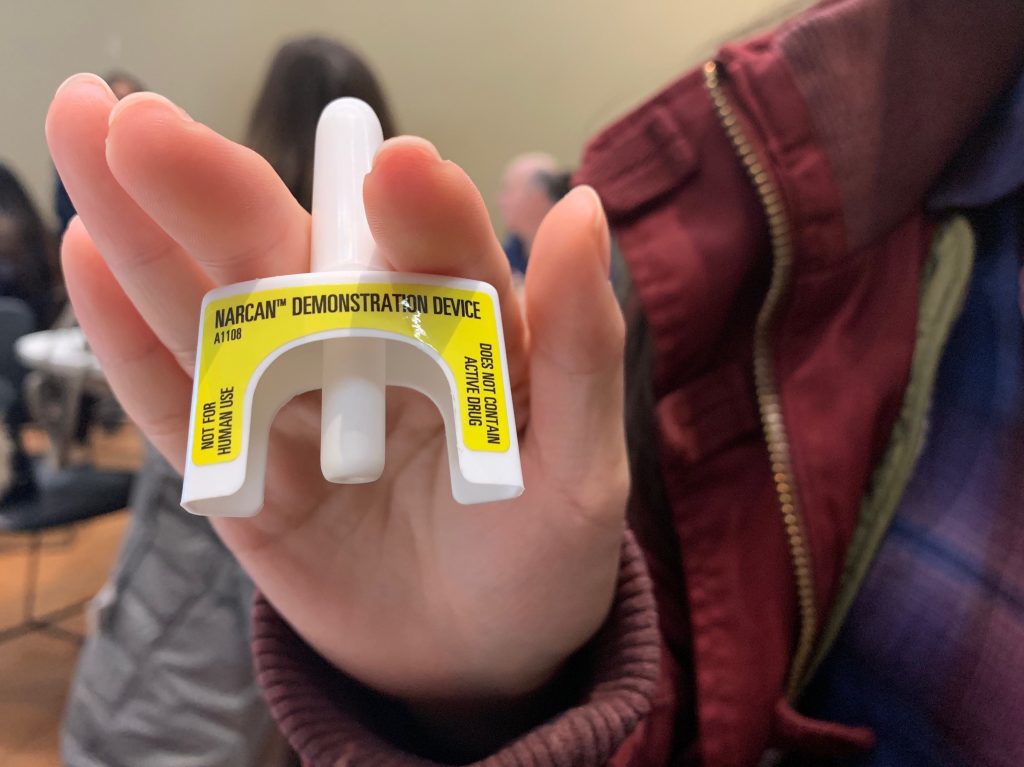

Lina Yae, a fourth year public health student at Ryerson, holds a practise nalaxone administration device on Wednesday, March 27, 2019. Yae attended the third of the four training and information sessions put on by the CSSDP. (Emma Sandri/JRN 273).

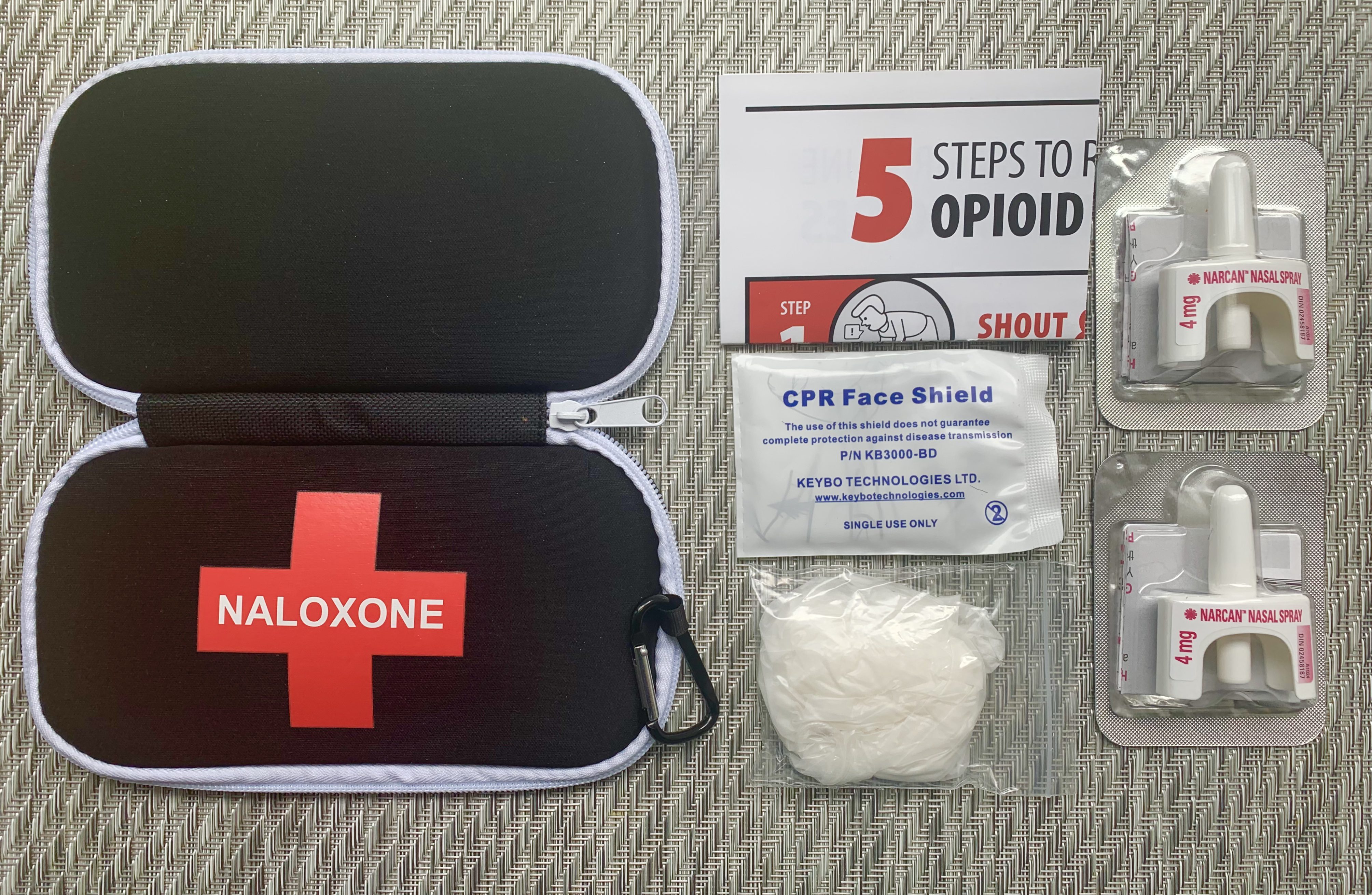

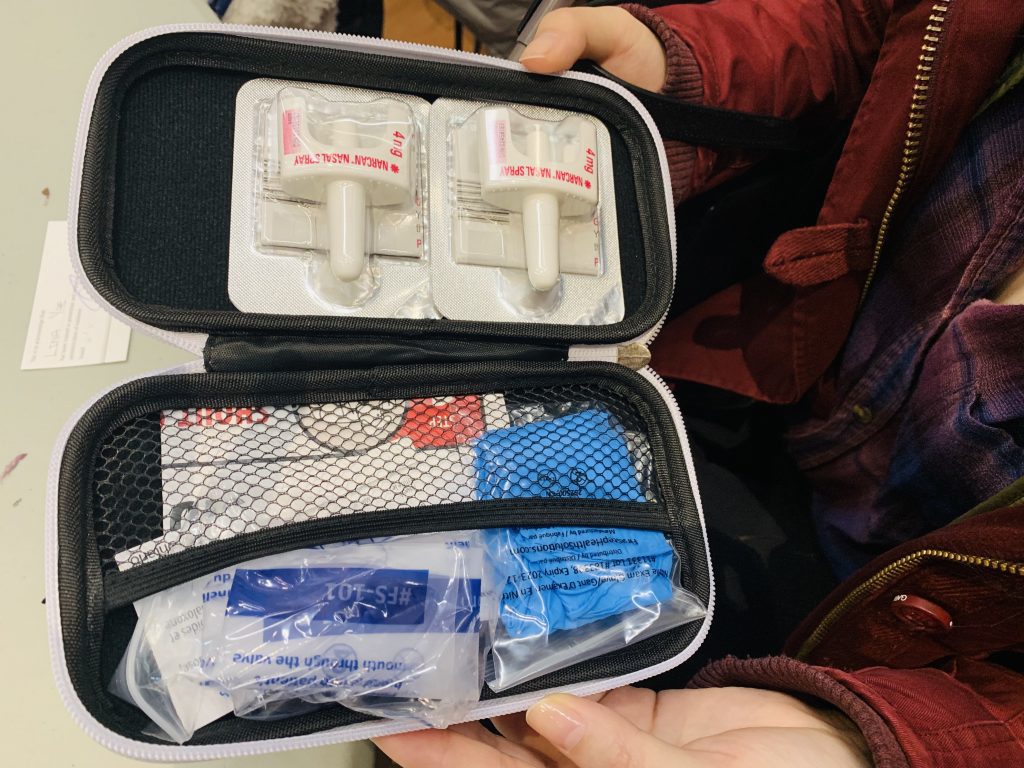

After having attended the session, Yae receives a naloxone kit free of charge. The fourth-year said she attended the Wednesday, March 27, 2019, session after she had heard about the opioid-reversing medication in class. (Emma Sandri/JRN 273).

The efforts of the CSSDP to draw students into the conversation around opioids has also captured the attention of Ryerson faculty. Pascal Murphy is a professor at Ryerson who has been teaching a course called Homelessness in Canadian Society for about 10 years. The course has had a lecture devoted to exploring the tools of harm reduction since around 2010. It’s a popular class he notes, one that Fricker once took. “Students are using substances and students are living in families who are using substances,” he said, adding that everyone should have the right to a life without harm.

While Murphy and the CSSDP have never worked directly together, he says he applauds all of Fricker’s efforts, adding that the group’s advocacy is essential to the university and to students. “I don’t want to find any student dead in a bathroom because they didn’t get the proper tools, the proper education or the proper support…all of us should be looking toward [the CSSDP] and asking ourselves how we should support them.”

In his lecture, Murphy discusses the use of naloxone kits, a tool that Fricker advocates students to equip themselves with. In the last week of March, the CSSDP held training sessions with the kits, teaching students how to recognize the symptoms of an opioid overdose and how to reverse it. It’s towards the end of the term, a time when campus events can pass by unnoticed and unattended, as students and staff begin to hunker down for exam season. Yet, the seats are filled in the large beige auditorium at the university.

With her hair slicked up in an elegant bun and a stack of papers in her hand, Fricker shouts over the scraping sound of chairs, “Let me know if you don’t have a form.” The students flock to the tables, awaiting their chance to get a kit. Soon enough, a CSSDP Ryerson member comes around, carrying a big red crate filled with the little black cases—each emblazoned with a cross. He places them on the table in front of the students. Those who complete the session will get two intranasal doses of naloxone and the power to save a life.