By Hannah Mercanti

It’s already started by early morning, long before the shoppers have arrived. The clock strikes 10 and a bustling crowd of young artists clad in styles from trad goth to classic raver pile into the rented venue on Abell Street, bags full of handcrafted and curated goods, ready to set up for the busy days ahead.

In an hour, the grey, concrete, two-room venue will come alive as a colourful celebration of community and culture, packed with people hailing from all sorts of alternative scenes across the GTA.

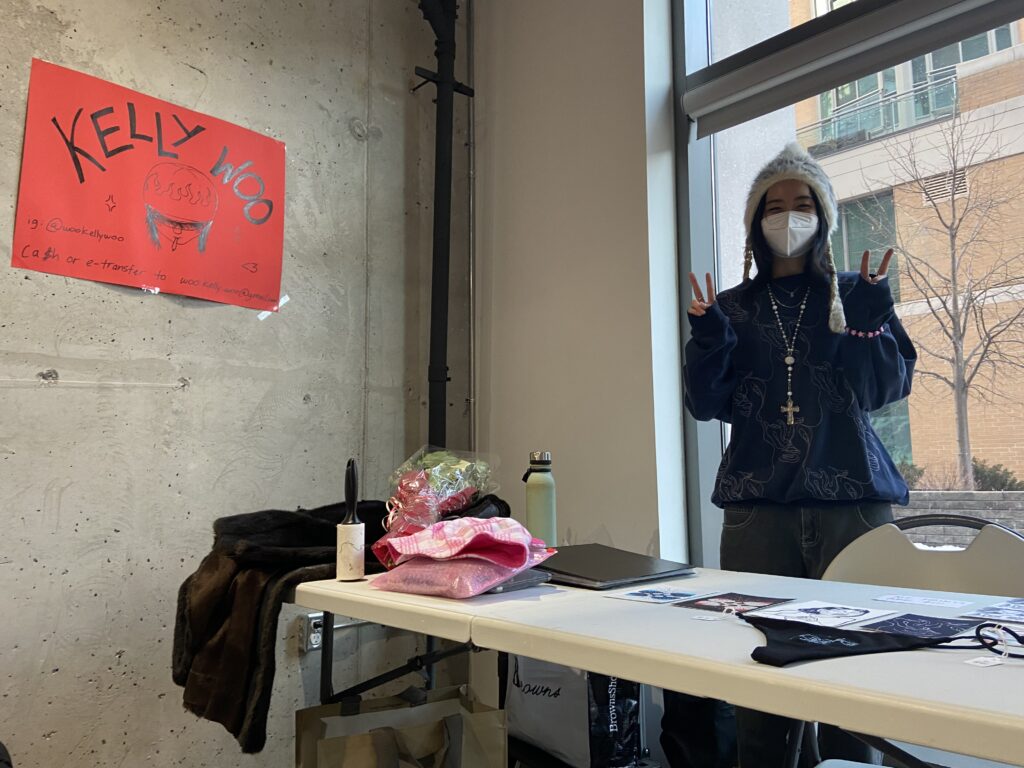

As soon as the doors open, it begins in a flash. Hand-decorated signs scotch-taped to the walls are the backdrop for the diverse group of sellers and buyers, chatting loudly while an upbeat hyperpop song blares. Quickly, it becomes clear that everyone is ready to be back – and has been for a while.When COVID-19 lockdowns put a seemingly endless stop to in-person activities, alternatives active in the LGBTQ+ and BIPOC communities felt they had lost touch with a group that had once been like a second family. Eventually, 17-year-old event planner Estella Maise decided the disconnect had to end.

“I was raised by punks and ravers, so it’s sort of my ode to ’90s underground subculture,” says Maise, referring to the grungy paper flyers stapled around the city promoting the DIY flea market hosted by Estella Originals, Maise’s event planning company.In a desperate attempt to create an in-person space amid rigid pandemic guidelines, Maise decided to host a small, impromptu DIY flea market in 2021. Originally, it took place outside on Islington Avenue on a hot summer afternoon with four vendors lined up – a fraction of the 30-plus vendors now gathered in the trendy downtown neighbourhood of Queen West.

Many of the eager participants are female, BIPOC or members of the LGBTQ+ community – groups with extensive histories of facing barriers in the creative industries.

In Toronto, 41 per cent of LGBTQ+ small business owners reported problems getting bank loans, while 33 per cent said they had trouble networking, according to a May 2021 business analysis from the Canadian Gay and Lesbian Chamber of Commerce and consulting firm Deloitte.

It seems Canadians in these communities haven’t been able to catch a break. According to a February 2022 report from Statistics Canada, average weekly earnings were lower among women and BIPOC Canadians than male Canadians in all sectors.

BIPOC and female Canadians in these sectors consequently have less pocket money than their white male counterparts. Yet, typical market spaces in Toronto can still cost upward of $150 – Maise and her team charge $30.

“We take a lot of pride in hosting something outside of the stereotypical market space,” says Maise, a wide grin making its way across her face. Looking back on the unlikely success of the first market that fateful summer afternoon, she began to form an inclusive, creative space for BIPOC and LGBTQ+ people, starting by giving them first crack at running stalls.

In the bright light of the early afternoon, Hyla Golden Del Castillo’s mini-pliers shine from her cozy spot in the corner of the venue’s second room. She wraps quick, elegant rings out of stainless steel wire for those who stop by to chat, asking “Gold or silver?” with a contagious smile.

A seamstress and jeweller hailing from Colombia, she says several of these creators realistically do not have time to promote their work, which can slow their momentum to almost a halt. Many have school or jobs to focus on as well as their small businesses, which doesn’t leave much time for functional self-promotion.

A seamstress and jeweller hailing from Colombia, she says several of these creators realistically do not have time to promote their work, which can slow their momentum to almost a halt. Many have school or jobs to focus on as well as their small businesses, which doesn’t leave much time for functional self-promotion.Del Castillo herself wouldn’t have been able to make it to the market if Maise and her team had not provided a table, clothing racks, hangers and promotional material.

She breaks out into an infectious burst of laughter as she describes how normally, she transports her supplies in a bright pink plastic pull wagon. “Not many of us have access to reliable transportation,” Del Castillo explains, saying there was no way she could have brought the necessary supplies on her own. “Imagine me trying to bring a table down the street in a wagon. It’d look ridiculous!”

A quick walk away from Del Castillo’s booth stands Baie McFadden of Floral Dissonance, a small, cozy knitwear business, surrounded by a crowd of buyers hoping to snag one of her infamous items before they inevitably sell out.

Positioned in the centre of the venue’s main room, her booth cannot be missed. A light pink tablecloth rests on a grey, plastic table below an array of fuzzy handmade apparel, including colourful hats, gloves and bags, some lovingly decorated with hand-stitched hearts and designs.

She is in her element, donning a bright purple silk dress with purple highlights in her dark hair to match, laughing with customers and fellow sellers while she twirls around her decked-out booth in her high-heeled, white vinyl platform boots.

“Having a space with other queer femmes makes a world of difference,” says McFadden, leaning over slightly to carefully take down the miniature pink construction paper sign for her now sold-out fingerless gloves.

Along with other vendors, she feels more comfortable selling at the DIY market surrounded by her community than at events with no focus on inclusion. “It feels safer and more welcoming,” says McFadden, relaxing behind the table with her booth partners.

Within the creative scenes in Toronto, people like McFadden and Del Castillo have grown to associate alternative events with the overwhelming, oppressive presence of straight, white male voices – but the sellers aren’t the only ones who have been trying to escape this experience.

Vanessa Benitz, a student living in Toronto’s downtown, visited the DIY flea market on her roommate’s suggestion, expecting a typical pop-up, which in her mind consisted of bored salespeople surrounded by crowds of equally uninterested buyers.

But when she arrived, she knew she had been wrong in her assumptions. To her surprise, the market provided a space for her to meet new creatives in her community and reconnect with those she already knew in a personal environment that had been lost to the pandemic.

As she peruses the booths, stopping at Floral Dissonance to pick up a heart-shaped crochet bag in the pastel pink, blue and purple of the bisexual flag, she knows she’s in the right place. “I feel way more safe and comfortable,” says Benitz.

Like so many of those around her, she has found a small place within her large community where she fits in. Stepping back out into the cold air, she has one thought on her mind: “I can’t wait for next time.”