By Atiya Malik

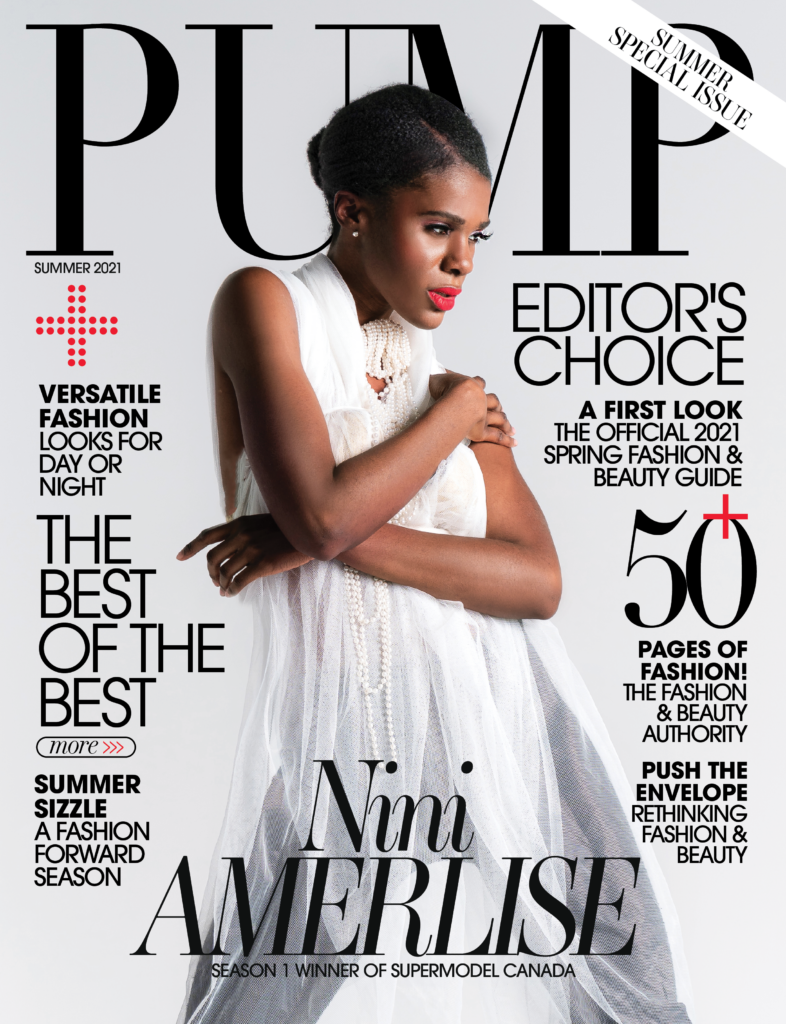

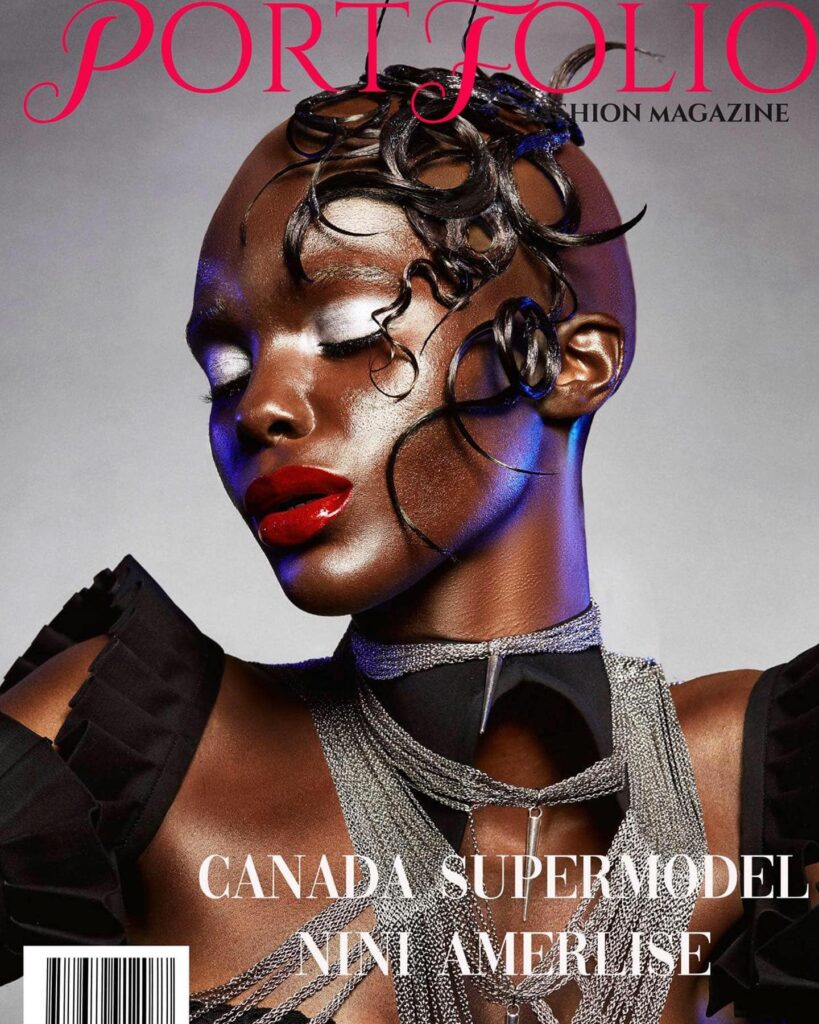

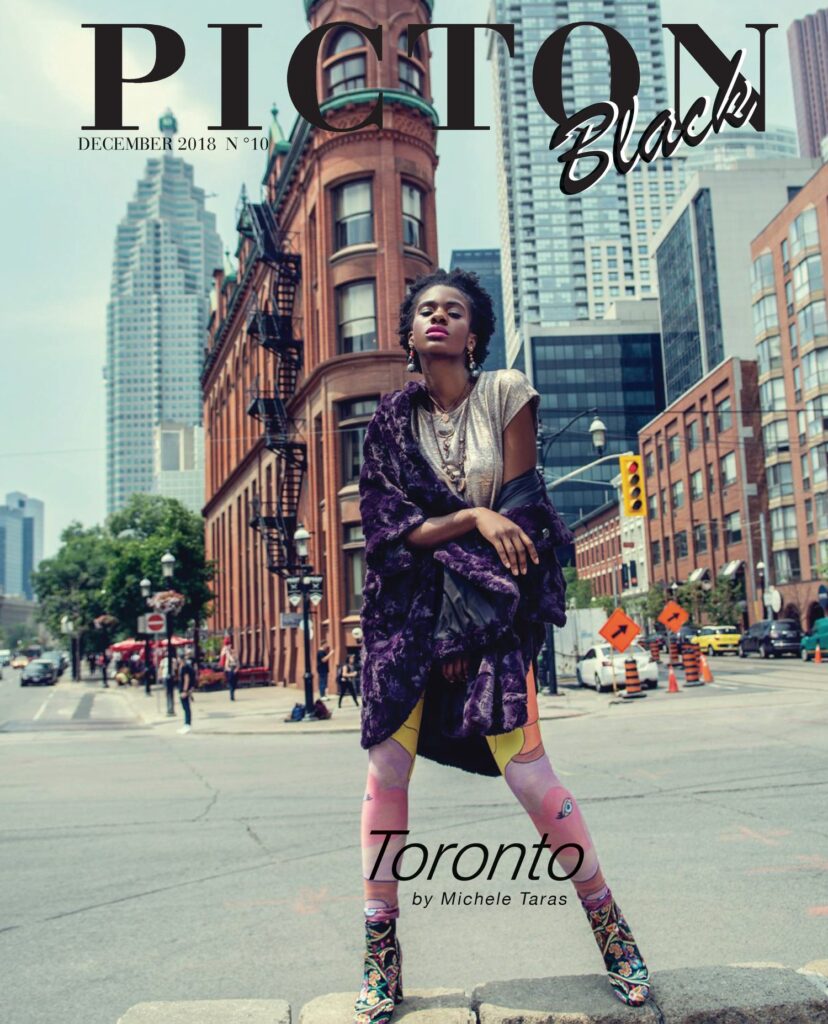

Nini Amerlise is walking the runway in Toronto’s Fashion Week but the only thing on her mind is the colour of her skin. She doesn’t feel or look like herself because her foundation doesn’t match her deep golden-brown complexion. All she can think about are the bright white lights shining down, making her hyper aware of her makeup. She runs to the bathroom to try and salvage the look with her own products. Why is diversity so difficult?

“They had a hard time finding my shade. They had a hard time figuring out what to do with my hair,” said Amerlise, an award-winning supermodel. “The stylist would sugar coat the situation and say, ‘Oh your hair is perfect, we can just leave it as is.’ Whereas, everybody else is getting dolled up and it’s just me who isn’t.”

Despite Toronto’s image as a multicultural hotspot, the fashion industry is years behind in embracing diversity and inclusion, experts say. Amerlise’s experience plays out in similar ways for many Black women working in fashion. People in the industry say it all comes back to one problem: The lack of diversity among those in power.

“If you look at the fashion industry itself and the positions that exist, very few of them at the high level are held by women, much less women of color,” said Dr. Alison Matthews David, a historian and professor in the School of Fashion at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU).

David says there are hierarchies in fashion. While Black and brown women are making garments all over the world, those in power or in high-profile roles are still largely white men. There isn’t enough diversity around the table to influence greater social change, she says.

In addition, David noted that fashion is not recognized or protected by Canadian content laws, and there is little provincial or municipal funding to support fashion as an art form. Quebec is the only province to offer some level of government support for fashion, according to the federal government.

While some major retailers appear to support Black creatives by showcasing their work, it’s often token representation, insiders say. Nothing, according to fashion blogger Yvonne Ben, is more discouraging than picking up your phone or walking into a store and seeing major brands charging top dollar for African collections produced out of thin air.

It’s even worse when brands only promote those collections for a short period of time, such as during Black History Month, to seem socially aware or trendy, said Ben.

David emphasizes that a trend is temporary and does not create permanent change.

During the pandemic, everyone preached body diversity for all shapes and communities. Now, however, runways are back to focusing on size zero models, she said.

Fashion’s lack of diversity can be directly seen in a recent promotion by some brands, including Levi’s, which used computer-generated models to replace representation in size, skin tone and age.

“This is not diversification in the fashion industry, this is exploitation,” says David, who is not from the Black community but works to promote social change in fashion.

Catherine Addai launched Kaela Kay, a boutique in North York, 10 years ago because she struggled to find West African fashions in the city’s stores. With a wedding approaching and her usual designer unavailable, she was left empty handed. All she desperately wanted was to wear a dress made with ntoma, a handcrafted cloth from West Africa, to showcase her beautiful and vibrant Ghanaian culture.

Seeing her frustration, Addai’s mother bought her a sewing machine. One machine, one sewing book and material from Fabricland and she had created a dress that had heads turning.

However, her brand has not been welcomed with open arms everywhere. Before the pandemic, a major mall retailer, which she chose not to name, decided not to carry her designs because they did not think their clientele would be interested in her bold prints and patterns.

“Clothing is clothing. A dress is a dress. The only difference between my creations and items on the other racks are the colours. You can’t tell me your clients won’t take interest in colours,” said Addai.

Despite Toronto’s multiculturalism, Colette Liburd says the lack of Black representation in fashion is linked to the microaggressions she has experienced as the co-owner of two The Clarendon Trading Company stores selling vintage and streetwear apparel.

Customers have approached her with questions she sees as inappropriate and racist, such as “Who are your investors?” or “How much do you pay for rent?” She wonders if her skin was a different colour, would shoppers still be asking who her investors are?

Her solutions are rooted in seeing more Black women in the media, the retail industry and other fashion-related fields to eliminate the shock factor. Liburd says it’s about time Black women in fashion are normalized.

TMU’s School of Fashion, which is considered the country’s leading university fashion program, has just one active Black professor. For Karen Dearagao, a second-year fashion communications student at TMU who is often the only Black student in her classes, feeling represented matters.

“I feel like I’m facing impostor syndrome because I feel like I don’t really belong,” said Dearagao.

For her part, Nini Amerlise says Toronto’s fashion industry should embrace and promote diversity by seeking out partnerships with organizations that hold similar values. It is difficult to create change when the brands providing the funds do not support it. She also says fashion designers and companies must start booking many models from diverse backgrounds, not just one or two, to move past token representation.

Amerlise says these changes will serve the city’s fashion scene in the long run. The future of the fashion industry for Black women in Toronto is in the hands of those in power.