By Parker Theis

When Asha Swann entered the nondescript office building for the Toronto branch of Vector Marketing in 2017, she was excited about the prospect of her first job. She was placed in a room with other teens and told that they would be interviewing for a cutlery company called Cutco.

They were shown an infomercial about the Cutco products that they would be hired to sell, and then a man came in to speak to them about his success within Cutco. “He’s like, ‘I’m making six figures a year. I started out just like you guys when I was 16 and you can make tons of money selling these knives,’ and he does this demo where he’s just chopping fruit like a mad man,” said Asha. “And then he whips out this pair of scissors and he’s like, ‘They also make scissors that can cut through pennies. They’re so powerful, this is the only pair of scissors you’ll ever need in your life. I’m 15 and I think this is the coolest thing I’ve ever seen.”

Social media has the capacity to make people more vulnerable to scams, and some companies are known to use that to their advantage, such as multi-level marketing companies. Accounts reach out to people through direct messages offering opportunities for self-sufficiency and easy money-making through their employment. Though companies like this have existed for years, their recruitment tactics have changed and adapted.

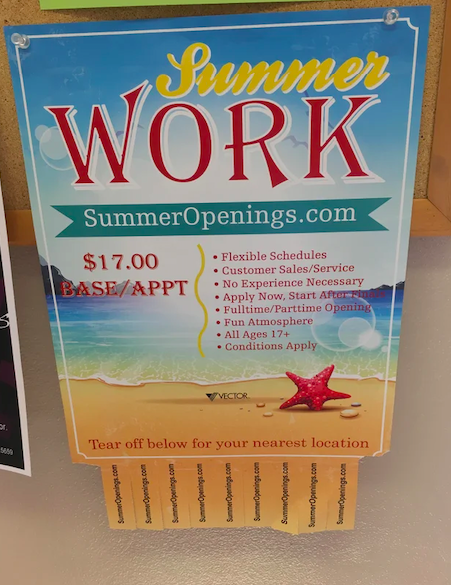

Typically, Cutco advertises in newspapers and on fliers posted on bulletin boards at college campuses, but the advertisements tend to leave out the name of the company and/or the nature of the job. This is what drew Asha in.

When she was looking for her first job, the ad she clicked on only advertised the pay and the demand for students.

“They’re offering $18 an hour, you can’t even get that, like what more do I need? I have concert tickets I want to buy. I want to get a bus pass. Like I’m 16, that’s all I want,” Asha laughs.

“After like an hour, he makes this really serious statement, saying “by the way, Cutco is NOT a pyramid scheme.” He kept stressing how Cutco wasn’t a pyramid scheme, and I was like I barely know what a pyramid scheme is like I got English homework to do. So he keeps telling us how it’s not a pyramid scheme; it is a Multi-Level Marketing Company that is totally legal and regulated by the Canadian and U.S. governments. And I just thought nothing of it.”

When Swann came home from the interview, glowing at the prospect of making her own income for the first time, her mom recognized the business model immediately, “I’m so excited, I was like, ‘I went to the first interview, and hopefully they like me, and I hope they bring me back for a second interview,’ and my mom says “This is a scam.” I was like “No, no, no, it’s not a pyramid scheme. It’s a multi-level marketing company, and it’s accredited by the U.S. and Canadian governments,” said Swann, “I’m borderline quoting the guy from the video, and so my mom says, “You, sell to people, who sell to people, who sell to people? That’s the shape of a pyramid.”

Founded in 1949, Cutco’s website states that they are “the largest manufacturer of kitchen cutlery in North America,” with more than $200 million in annual sales for their knives, utensils, and a whole slew of kitchenware. Since its inception, Cutco, a subsidiary of Vector Marketing, has been involved in numerous different lawsuits for deceptive recruiting tactics, unfair labor practices, and refusing to pay its workers. Cutco uses a controversial business model called multi-level marketing or MLM. The United States Federal Trade Commission and the Canadian Competition Act define MLMs as “businesses that involve selling products to family and friends and recruiting other people to do the same.” Sound familiar? Yeah, it sounds like a pyramid scheme.

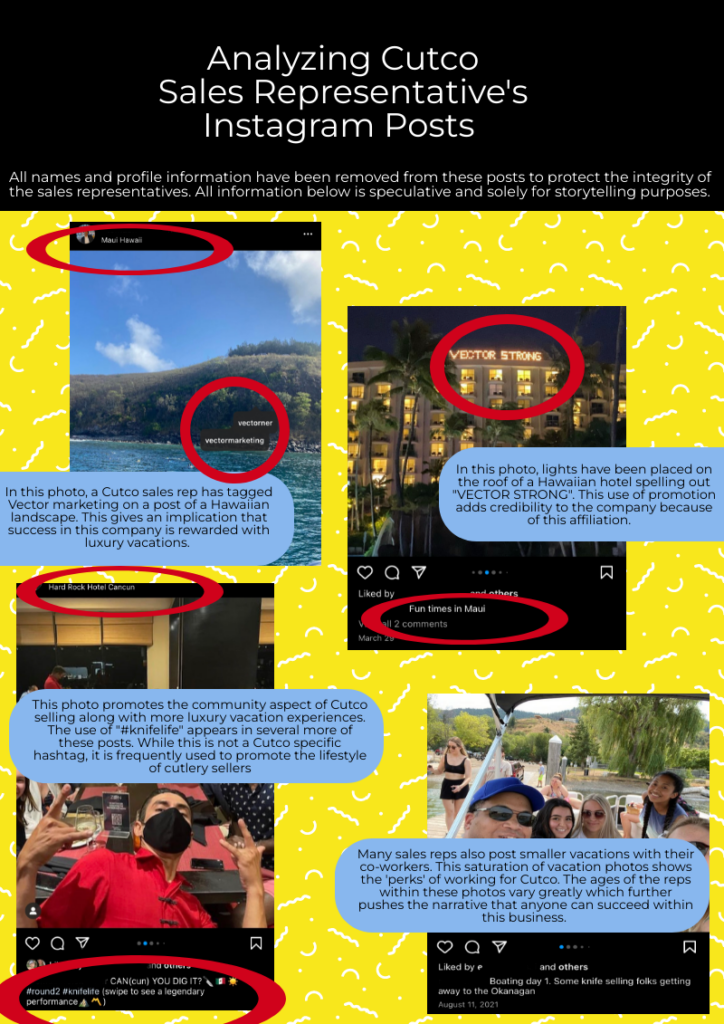

Despite repeated requests for comment, a Cutco spokesperson was not available for an interview. According to a 2015 copy of the Cutco representative sales agreement, sales representatives are not allowed to explicitly state that they are working for Vector or Cutco. Although they aren’t allowed to promote the company, sales representatives are able to promote the luxurious lifestyle of a knife-selling employee by oversaturating their feed with pictures of boating excursions, island vacations, red-carpeted events, and large seminars with hashtags like #knifelife. This kind of promotion as well as solicitation through social media creates the appearance that anyone who joins can reap these benefits.

MLMs have been under fire for decades now because of the glaring similarities between their business tactics and the tactics used by more prominent pyramid schemes. The FTC differentiates between the two by stating in bold, “If the MLM is not a pyramid scheme, it will pay you based on your sales to retail customers, without having to recruit new distributors.”

This is key to understanding the gray area where Cutco exists between legal MLM and illegal pyramid schemes.

According to Michael Weinberger, an MLM lawyer with Siskinds in London, Ontario, “What the law says is that it’s very easy and it’s very hard to maintain direction and control of all the independent distributors that you have [in an MLM]. So you have to train people, and as long as you train people properly, and as long as you genuinely take the rules and regulations seriously, then you will not be considered as operating a pyramid scheme, you’ll still be operating an MLM plan.” To summarize, all pyramid schemes start off as MLM plans, the difference lies in if the company cracks down on individuals who break any laws separating the two business models.

But if this model has been around for so long, why are people still falling for it? How do they not know it’s a scam? Because of the pandemic, many people who lost their jobs began seeking employment in other ways. Vector, the parent company of Cutco, announced the temporary switch from door-to-door to virtual sales calls because of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. This has encouraged more young people to apply for jobs with the company. A job that pays above minimum wage and allows work from home? This is what drew Journalism student Bashair Ali into applying during the beginning of the pandemic.

When Ali wanted to make some money while in her first year of online university, she began looking on the job search site Indeed. She stumbled upon a job that advertised remote work, flexible hours, and above-average pay. She did not know exactly what she was applying for, but was excited about the money she would be making. After applying and being hired, she began remotely selling for Cutco in 2020.

“It was basically a webinar. I would just go through the PowerPoint with the people on Zoom,” she said. “It would actually take a long time. Sometimes people would ask questions, usually, they didn’t, and people got really bored when I was doing it.”

Unlike what is common in MLM plans, Ali received compensation for the sale she made, “[I was selling] a gardening set. It was like $116. I only got $65,” said Ali. “I did four interviews and they paid me $15 an hour because my commission pay was $5 extra. They forgot about that money [the hourly pay advertised], the $60, I only got $65.” The ad she responded to did not specify that they would only be paid based on commission.

But why directly advertise to teenagers? Weinberger says it’s cheap labour. “The barrier for entry into direct selling is very, very, very, very low,” he said, “essentially you get a business in a box for $50.”

In Ali and Swann’s cases, they paid closer to $80 for their entry into the company. Weinberger shared that other MLM companies have potential sales representatives pay $8,000 for hundreds of products to be sold at double the cost. “It helps to have a low barrier to entry, because I don’t know many students who have $8,000,” he laughs, “But are they going to make a lot of money? Probably not.”

Swann left Cutco almost immediately after joining. The ‘penny cutting scissors’ she had received became a gift to her grandmother that year for Christmas. Ali worked for Cutco for less than a month before she left. Neither harbors any resentment towards Cutco, and after the experience, they will be wary of unaffiliated job listings that sound too good to be true. “It just seemed very messy,” said Swann. “Looking back, I’m very glad I didn’t continue with it even though I was really mad about being out $85.”