By Caelan Monkman

Across from Carleton University in central Ottawa, next to an arena-turned-COVID-19 testing centre, sits the Brewer Park Oval, one of Ontario’s only long-track speedskating ovals. An outdoor ice surface, it relies on the city’s cold weather to stay refrigerated — some years, provincial competitions are cancelled when warm weather melts the ice. It’s maintained by a group of dedicated volunteers who work all winter to keep the ice ready for the athletes of Ottawa’s two speedskating clubs, and budding future Olympians.

Michel Rivet, head coach of the Gloucester Concordes speedskating club, can be found there most days coaching skaters or maintaining the ice. But at 3:30 a.m. on Tuesday, Feb. 15, he sat proudly in his living room, eyes glued to his television as two of his proteges from Brewer Park made history.

More than 10,000 kilometres away, inside Beijing’s National Speed Skating Oval — nicknamed the “ice ribbon” due to its design – members of Canada’s women’s team pursuit squad were standing atop the Olympic podium, smiles on their faces, gold medals around their necks. The trio of Isabelle Weidemann, Ivanie Blondin and Valerie Maltais quickly became household names across Canada, especially Ottawa’s Weidemann, who had already won bronze and silver medals at the Games and would go on to carry Canada’s flag for the closing ceremonies.

Though all three athletes now live and train in Calgary, it wasn’t long ago that Weidemann and Blondin were training and competing at Brewer Park, under the guidance of Rivet.

“We’re always in communication,” says Rivet. “Both Isabelle and Ivanie called me before they left to go to China.” Before and after the race, Rivet was on the phone with their families, spending the moment “sharing that pretty special time.”

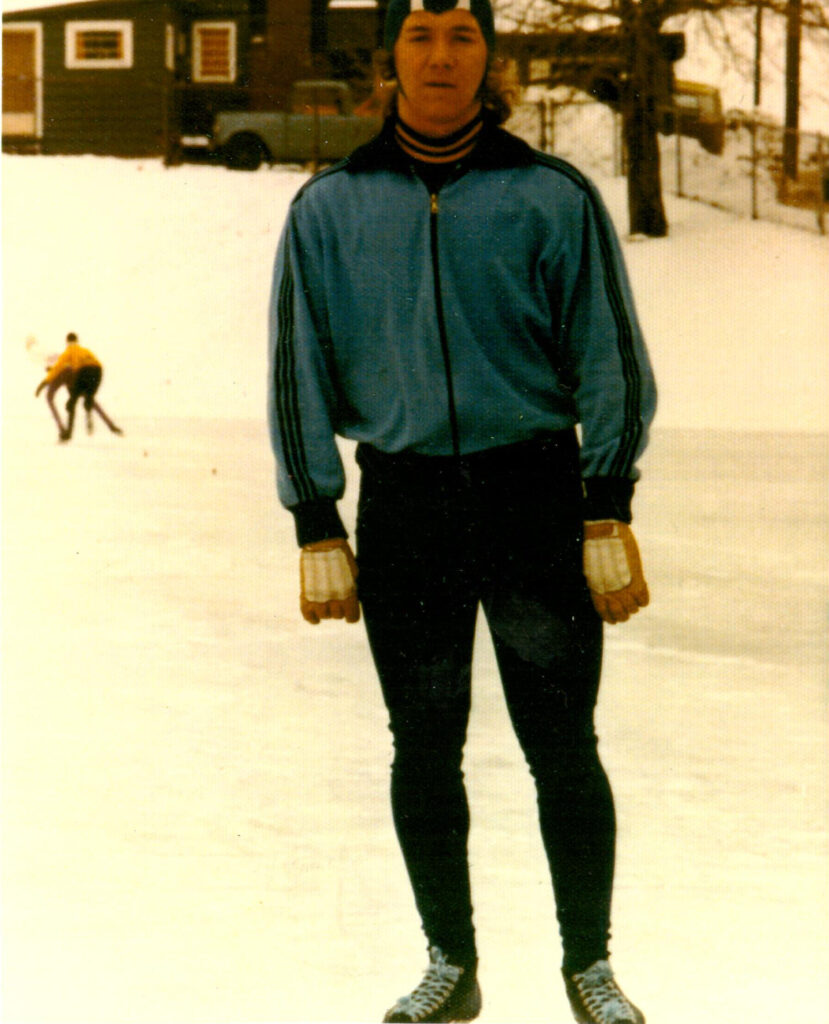

Rivet has been involved with speedskating since 1963 and in 2013 became the head coach of the Gloucester Concordes, the east-end speedskating club where Weidemann and Blondin began their careers. After achieving success as an athlete, Rivet coached several athletes who went on to compete in World Cups and the Olympics.

Anglesea Square (Now known as Jules Morin Park) used to be the home of Ottawa’s long-track speedskating oval. Click to see what the park looked like in 1956 vs. today.

He grew up half a block away from Anglesea Square (renamed Jules Morin Park in 1989) in Ottawa’s Lowertown. The park is the capital’s oldest public square and in the winter months of Rivet’s youth was home to a 220-yard skating oval — though speedskating coach Jack Barber pushed to double it to 440.

In the 1950s and ’60s, the park was a hub of activity in the wintertime. Kids sat and laced up their skates on rows of benches surrounding the ice as couples skated hand-in-hand. The sound of blades carving through the ice could be heard above the backdrop of classical music. A small wooden shack with a pot-bellied woodstove sat to one side of the oval, drying snow-drenched mittens and thawing frozen toes.

Like most Canadian boys, Rivet’s skating journey began in hockey skates. But intrigued by the speedskaters practising just 300 metres from his house, he joined the Ottawa Speedskating Club at the age of six in 1963. Barber ran the club and, according to online accounts, encouraged local kids to join and for 10 cents he rented speedskates to anyone interested.

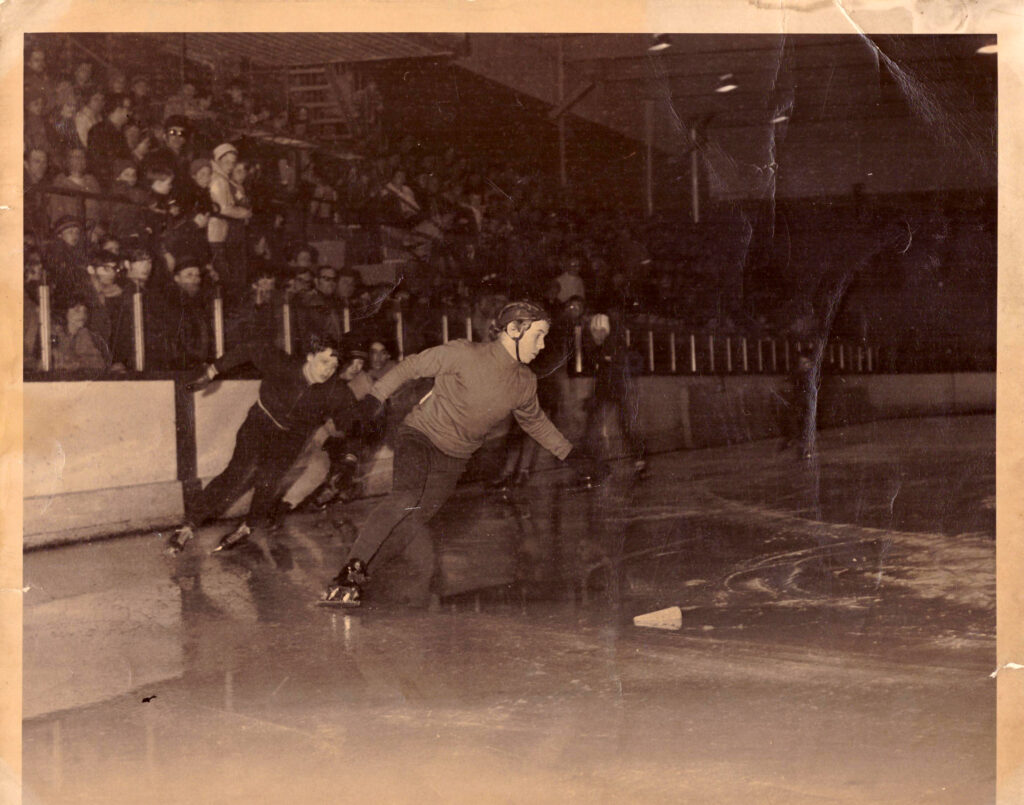

Rivet quickly excelled at the sport. In 1967, he won the Ontario championship in his age division, and alongside fellow Ottawa skater and future Olympian Gerry Cassan competed for Ontario at the Canadian Speedskating Championships in Winnipeg.

In 1974 in Ste-Foy, Que., Rivet and Cassan became the first two Canadians to compete in an international short-track competition. Short-track, which wasn’t an Olympic sport until 1992, “was filler in preparation for long-track,” Rivet recalls.

Later that year, as Rivet’s career was taking off, his father got sick and became unable to work. To help support his family, Rivet got a job in construction and stopped competing, eventually giving up skating completely.

“It’s unfortunate for me because I was on a good curve,” says Rivet. “But I’ve got no regrets, it’s just something that happened. I just needed to get to a job quickly and put some money in my pocket for the family.”

He hadn’t skated for about five years when he met his future wife, Carleen, in the fall of 1979.

“As I got to know him and his family, the concept of skating came up everywhere,” says Carleen Greyeyes-Rivet. “He was always talking about speedskating, and I said to him, ‘I wish I’d seen you skate.’” (Ironically, Greyeyes-Rivet, who was born and raised in Saskatchewan, had seen Rivet skate in the 1971 Canada Winter Games in Saskatoon, though the two wouldn’t realize this until years later.)

Following his engagement to Carleen, Rivet returned to the sport and began coaching. His career in labour relations sent him all around Ontario, and over the ensuing years, Rivet coached in towns across the province before his job brought him back to Ottawa, where he began coaching the Concordes with David Morrison.

“Mike’s interest is primarily long-track anyway,” says Morrison, who is now the manager of sport development for Speed Skating Canada. “So, it allowed him to take the lead on some of those long-track issues and then my focus was really as the head coach of the overall program.”

With both the Gloucester Concordes and the Ottawa Pacers, Ontario’s long-track sector has continued to grow and thrive under Rivet. “Mike was always a really supportive coach,” said Vincent De Haître, a former Gloucester skater and three-time Olympian. “He did a lot of good for Ottawa speedskating.”

“If Mike wasn’t so passionate about long-track in Ottawa, Ontario’s long-track would be almost non-existent,” says Mike Murray, head coach of the Hamilton and Golden Horseshoe Speedskating Clubs. “There are just not other people that are pushing it supporting it.”

Looking back, Rivet attributes his passion for coaching to his childhood coach, Tony Winterink. (“If that isn’t a name for a skating coach, I don’t know what is,” jokes Greyeyes-Rivet.)

“He was motivating, a great mentor (had) great values. It’s kinda funny, the reason I coach is because of my coach. He was a good example.”

Rivet still gets together with Winterink several times a week for coffee, and the two enjoy discussing skating and skaters.

Despite the success of many of his skaters over the years, Rivet remains extremely humble. For him, he says, it’s about forming bonds with the athletes and helping them go as far as they wish to go.

John Weidemann, Isabelle’s father and a former coach alongside Rivet, says no one in the sport is as dedicated as Rivet. “He spends the entire winter and his dollars and his gas and everything, doing speedskating, and is genuinely concerned about all the athletes, whether in his club or not.”

Rivet is in his element at Brewer Park, working with kids and maybe another future Olympic champion. But through it all, Greyeyes-Rivet says her husband maintains a quiet humility and only wants to share his love and knowledge of skating.

“He won’t sing his own praises, ever,” she says. “He will coach the little kid who’s just learning to skate and may never progress out of speedskating the same as the kid who has the future in skating.”