By Clesha Felicien

The rhythmic pounding in her chest intensified as she forced her legs to persevere through the sweltering heat. All the animals seemed to cheer her on as she ran through the familiar pastures of her grandfather’s farm. She slowed down once she reached the cow pen and shyly greeted the two strangers in white coats. Her shoulders slumped as she watched the golden-brown dairy cow lay down on its side in pain. Sasha remembers her eyes widening in awe as the two men placed a metal circle to the cow’s side and put two rubber wires in their ears.

“This was the first time I had seen a vet,” says Sasha. “I was only six at the time. All I can remember is they gave something to the animals and they felt better.”

“I thought they were geniuses and I wanted to be a genius,” she says with a soft chuckle.

Sasha immediately decided to open her own veterinary practice and she skipped through her grandfather’s pastures in search of her first clients. Examinations were performed on dying mongooses, birds and lizards.

“I even did funeral services for the animals,” says Sasha. “I would make coffins out of whatever materials we had lying around, whether that was coconut shells or banana leaves.”

Dr. Sasha Black now holds her own stethoscope in one of the top-rated animal hospitals in Whitby, Ont.

Her lips are pressed into a straight line as she listens to the heartbeat of a six-month-old golden retriever. She gently pets his light brown fur until the anesthesia causes his muscles to relax into a temporary sleep. She transfers the dog onto the metal surgical table to begin the neuter procedure. The overhead light illuminates Sasha Black’s soft brown skin, causing her dark brown eyes and perfect white smile to appear as if they are glowing.

“During appointments and surgeries, I completely tune out the world,” says Sasha. “It is just me and the animal.”

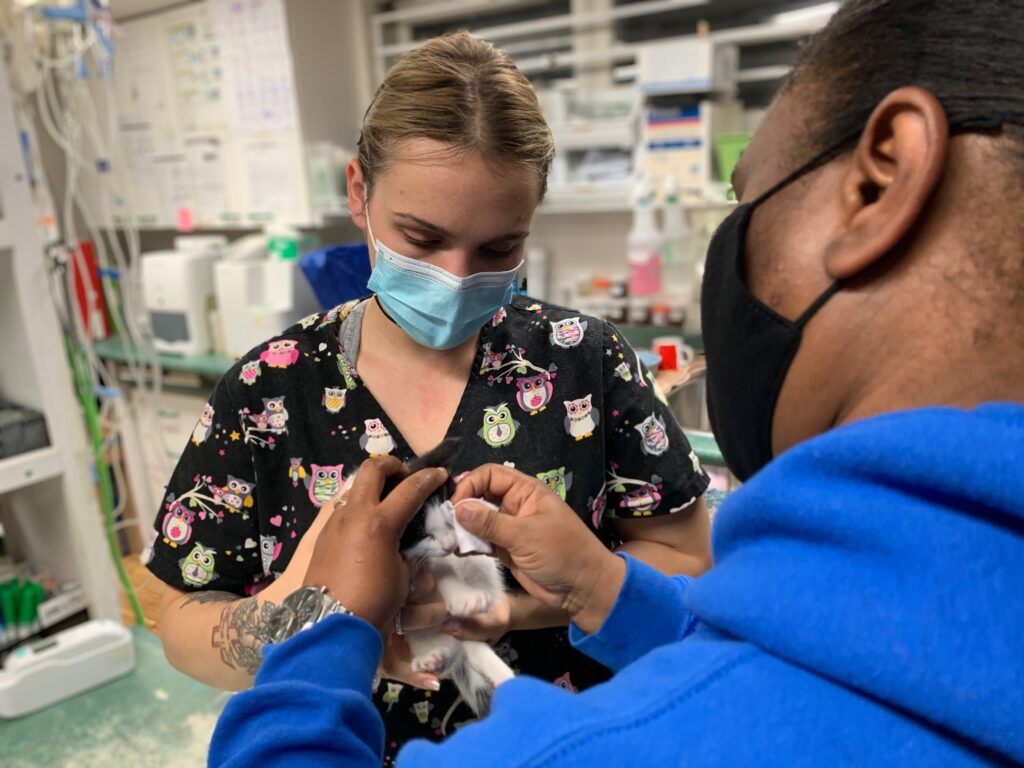

Sasha Black takes the temperature of a shih tzu experiencing an ongoing cough, on March 7, 2021. (Clesha Felicien/T•)

This six-week-old kitten is anxiously waiting for his first eye exam, on April 8, 2021. (Clesha Felicien/T•)

Sasha Black gently wipes away the discharge from the kitten’s eyes before prescribing some antibiotics to take home, on April 8, 2021. (Clesha Felicien/T•)

Within the plain white walls of the surgery room, Sasha hums along to “I Want to Break Free” by Queen. The area is small, containing a surgical table, a metal counter and some white cabinets. The ventilator beeps steadily like a metronome keeping the pace of her stitching. Spays and neuters are a proverbial “walk in the park” for Sasha as three to four surgeries are performed every Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday.

Small wrinkles form in the corners of her eyes as she smiles down at her finished work. Straight thick black stitches line the pale stomach of the golden retriever.

“I always knew I wanted to be a vet and I hung onto that dream and never let go,” says Sasha.

Her first stop on the road to becoming a veterinarian was the College of Agriculture, Science & Education in Port Antonio, Jamaica where she obtained her first degree. Unfortunately, there were no vet schools in Jamaica, so pursuing her dream career meant leaving her family, her boyfriend of seven years, and her home and moving to Tuskegee University in Alabama. With tears in her eyes, Sasha left Jamaica with the intention of returning after she completed her education.

In 2005, Sasha finished her residency, earning her the title of a veterinarian-board-certified in lab animal medicine. As a lab animal doctor, she studied safe animal practices when animals are used as subjects in a study.

After enduring a long distance relationship for five years, Sasha’s plans to move back to Jamaica quickly changed when she married her boyfriend, now of 12 years, The newly wedded couple moved to Canada to accommodate his construction job. At that time, she was a part of one per cent of Canada’s veterinarians specialized in lab animal medicine and the only Black Canadian in her field of practice.

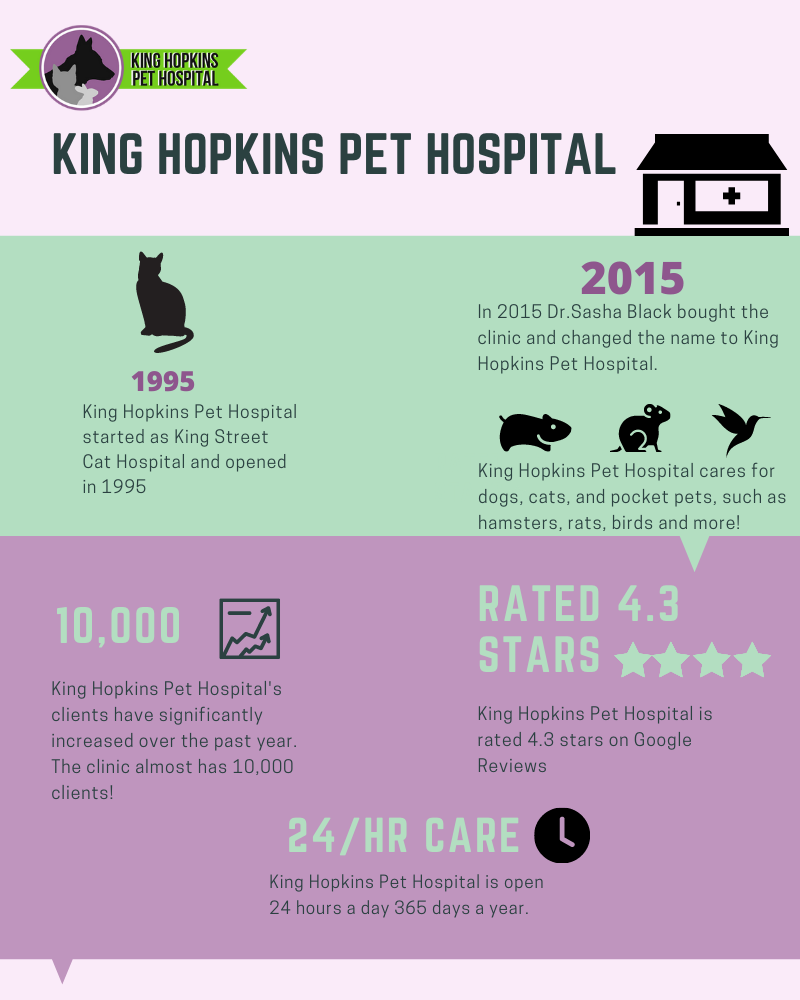

Sasha worked for 10 years in veterinary research before retiring her designation to spend more time with her three-year-old son and newborn. Sasha quickly realized that she was not ready to give up her passion, and after a year at home, she decided to purchase King Hopkins Pet Hospital.

“Owning a clinic comes with a lot of sleepless nights,” says Sasha. “You have to put in pretty much 50 hours a day.”

She heads out to work at 7.a.m. and there is a common routine.

Sasha covers a yawn as she slips on her black Nike shoes and throws her lime green winter coat over her shoulders. She slowly pushes the door shut, trying to avoid any sudden creaking noises. Her calves raise into relevé as her black shoes tiptoe across the white marble tiles towards the garage. Her heart is beating uncontrollably as she hears familiar sets of footsteps run down the stairs. Six-year-old Alexander and 10-year-old Connor squint their eyes and tilt their small heads up to lock eyes with their mother.

“Please don’t go,” Connor says as he grabs her leg. Alexander quickly follows suit and grabs the other.

“The time you miss with your kids can never be regained and that is the hardest part,” says Sasha.

Back at the clinic, Sasha removes her surgical gown to reveal plain black sneakers paired with blue jeans and a T-shirt that says, “Keep calm and come to King Hopkins.”

King Hopkins Pet Hospital is a small one-storey building no bigger than a two-bedroom house. The 24-hour veterinary clinic offers services for cats, dogs, reptiles and pocket pets including, hamsters, rats, birds and more. Within the vibrant green walls there are sounds of howling dogs waking up from anesthesia, phones ringing and soft laughter coming from the treatment room downstairs. The air is scented with the aroma of dog food, and disinfectant. with a slight trace of a pineapple candle burning on the reception desk. The clinic operates in organized chaos. One receptionist runs to the doctor’s office to fill a medication prescription while the other grabs a debit machine and sprints outside to bill out a client. The wind from the door causes a new client form to go flying and eventually land on the sandy brown tile floor. Receptionist Nadia Sabot rolls her eyes before picking up the paper and returning to the black reception desk only big enough for two chairs.

“It’s always busy around here,” says Nadia. “I am always running around.”

“Dr.Black expects a lot from us,” says Nadia, slightly out of breath, “but she is always there to encourage and reward you when you are doing your best.”

Meanwhile, downstairs in the treatment room Dr. Latoya Brown and Sasha are examining the next patient. A domestic shorthair cat with black and golden-brown fur is in distress. Brown’s bright green scrubs match the small green and white examination table.

“Doc, you need to come look, this cat is really not breathing right,” Brown says while frantically pointing in the cat’s direction.

“It needs emergency surgery. I am going to go call the owners,” Sasha says.

Brown reaches in the container above the sink for a syringe and sedation medication while Sasha reaches for the phone.

“Working for Dr. Black keeps you on your toes,” says Brown, “She is always happy and full of energy and I have never heard her say I am tired.”

Sasha’s hard work and dedication also does not go unnoticed by her clients. On the reception desks sits a large bouquet of red, pink, and white flowers, a token of appreciation from a first-time client who was pardoned the cost of an examination fee.

“As much as a couple times a week, Dr. Black is seen lowering service charges to help clients struggling financially. That just speaks to the kind of person she is,” says Nadia.

“If saving an animal’s life means sacrificing revenue, it is a small price for a bigger cause,” says Sasha with a smile.

Unfortunately, there aren’t always smiles at the clinic.

During her time at work Sasha has endured many racist encounters with some clients and co-workers she interacts with. Sasha never views her ethnicity as an obstacle, but the racist comments do not go unnoticed. Oftentimes, Sasha is identified by her race first and her designation second. The term “Black doctor” is the most common phrase Sasha hears. Sasha also recalls clients making it very clear that their dogs do not like Black people.

“I have had many racist encounters,” says Sasha “but I try not to let it bother me.”

Back in the treatment room, time is of the essence as Brown quickly ties the thin white strings of Sasha’s surgical gown into a neat bow. Sasha reaches for the stethoscope to check the heartbeat one last time.

She slightly holds her breath as she places the metal circle to the cat’s stomach and puts two rubber wires in her ears.

With a thumbs-up signal, Sasha places the stethoscope down and puts on her white rubber gloves for surgery.