By Claire Donahue

For 51 years, Factory Theatre has premiered a multitude of Canadian works from people of all backgrounds while creating a sense of comfort for those who walk through its doors

Matt McGeachy wandered about the centuries-old building on Adelaide and Bathurst, thinking about what amazing piece of theatre he’ll get to read next as Factory Theatre dramaturge. He turned the corner and found one such writer, who had found a bit of solace and shut-eye on a couch. He thought to himself, Does she live here? Did she sleep here last night? This is a frequent encounter for McGecahy. Whether it’s sleeping, eating, writing or acting, these nooks and crannies of the theatre have provided a sense of comfort for people like Indigenous writer and actor Yolanda Bonnell, and all others who enter.

Since its founding in 1970, Factory Theatre has been a capital for Canadian playwrights and actors. Factory became the first theatre in the country to produce exclusively Canadian plays. Some notable playwrights who have premiered plays at the theatre include Florence Gibson, Linda Griffiths and Andrew Moodie. Some of its patrons have included award-winning actors Emma Thompson and Ewan McGregor. This has made it a big part of the Canadian theatre scene.

Canada is known worldwide for its diversity. “When you walk out your door in Toronto you don’t look around and see only 40-year-old white men, right?” asks McGeachy. “You don’t hear people only speaking English. So why would our theatre not reflect the world that we live in?” McGeachy believes that the theatre’s current artistic director, Nina Lee Aquino, had a big role in making Factory Theatre as diverse as Canada is: “You see the impact that Nina’s work at Factory Theatre has had, I think I’m not overstating to say that she has transformed the landscape of Canadian theatre.”

Aquino has been with Factory Theatre since 2012, after forming the first Asian Canadian theatre company, Fu-GEN Theatre. She also became the youngest president of the Professional Association of Canadian Theatre. Over the years Aquino has worked in seven theatres across the country and created the first Asian Canadian theatre conference. “I try my best not to be swallowed by it,” Aquino says. “Not to be intimidated by my own labels, because you can. I still do at times, but, at the end of the day, it’s going to be all about the work that I do, and not so much the title.”

Factory Theatre is filled with lively people and conversations, but an old theatre comes with ghosts. Bonnell remembers a time she was sleeping backstage and felt as if a young girl’s feet were against hers. McGeachy is a bit more skeptical about the ghost but has heard many people at the theatre discuss their encounters with the supposed spirit.

Despite the ghost that may roam the halls, Factory Theatre is a welcoming and energetic creative space. Bonnell is a part of that diverse community. She joined Factory Theatre in 2015 when she submitted a play titled Scanner for the theatre’s The Foundry program, which helps people of colour in the community develop their plays. After Bonnell’s play was submitted, Aquino very quickly picked it up and Bonnell was offered a grant.

Bonnell recalls her favourite memory from the Factory Theatre: It was in the lobby, a modern all-around glass room attached to the older part of the building. She and four other playwrights were doing read-throughs. Other actors, writers and directors were there as well. Bonnell recalls being a bit nervous that day — it was one of the first times she had written a play that was to be performed by others. One of the playwrights was Skyped in from Montreal and encountered technical difficulties, so they duct-taped a picture of their face to some cardboard. In the end, the nerves were washed away with a memorable night. “It was just a really important night for the four of us and for Nina and for everyone else,” said Bonnell.

Now, the pandemic has forced many people from Factory Theatre to start working from home. A home doesn’t quite have the same atmosphere as the theatre, but it can be just as crazy. The Aquino household is full of creative minds, just like the theatre is. Her husband, Richard, and daughter, Eponine, are also involved in the dramatic arts. “All three of us are artists,” Aquino says. “We deal with chaos quite well. It’s something I’m not afraid of, so certainly my family is not.”

Often, all of the Aquino family members are in different rooms acting, creating or doing homework. Aquino says her husband sometimes records things in the closet. McGeachy, who also has a family, says his healthcare professional wife runs her clinic in their closet.

McGeachy had a hectic work life even before COVID-19. Around the theatre, he follows a pretty normal business routine. Answering phone calls, responding to emails and attending meetings. Although the work that McGeachy does plays a very important role at the theatre, he sees the most important part of his job as reading new scripts. “There’s always something swirling out in the world that writers are responding to, sometimes consciously, sometimes unconsciously,” he says. “So it’s really important to always be reading new scripts.”

Bonnell was one of those playwrights, submitting a script to the theatre and receiving a chance to show her talents. She greatly appreciates what Factory Theatre has been doing for BIPOCs like her. “They are trying to focus on new Canadian works and when we look at what the perspective of Canada is, that is diversity,” says Bonnell.

That old theatre can hold a lot of creative thoughts swirling around, ghosts roaming the halls, and comfy couches. The sleeping, laughing and chatting has created chaos and calm simultaneously in one space. Creators of all sorts sitting on the fire escape, couches, balconies and offices. In welcoming all communities, this theatre has become a community itself. This is Factory Theatre.

THE THEATRES ARTISTIC DIRECTOR NINA LEE AQUINO WORKING ON A PRODUCTION FROM HOME. MAY 7, 2020

RICHARD LEE/FACTORY

THE ACTOR’S VIEW. MAY 2, 2018 JANELLE HANNA/FACTORY THEATRE

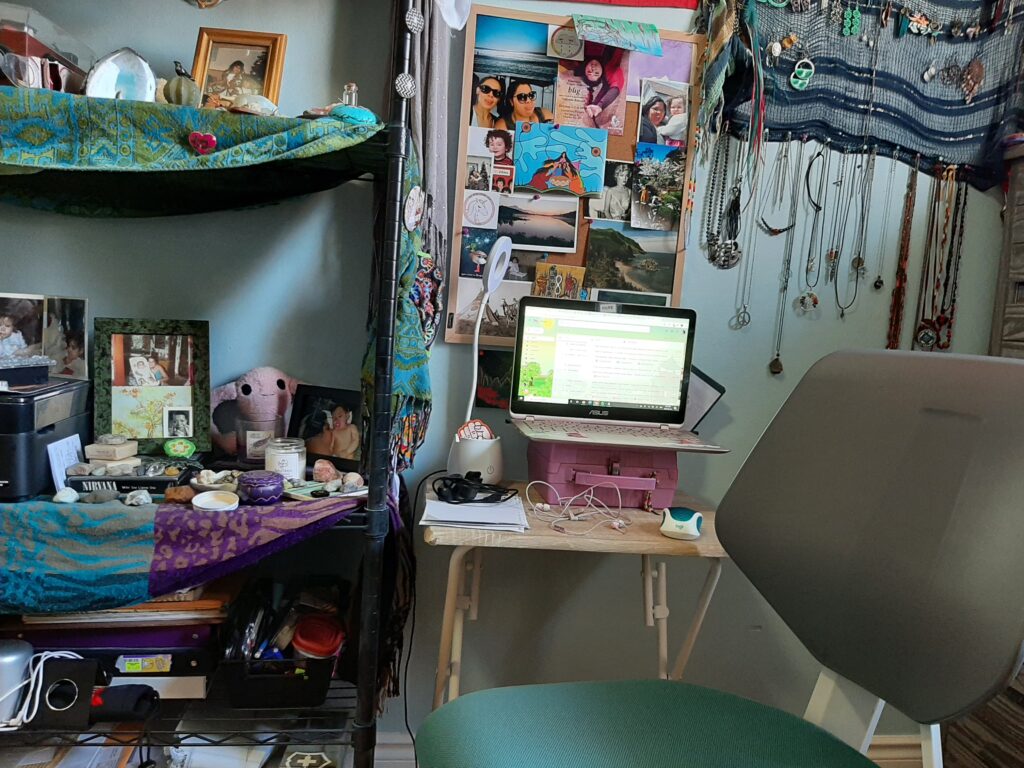

ACTOR AND WRITER YOLANDA BONNELL SHOWS OFF HER WORK FROM HOME SPACE. MARCH 15, 2021

YOLANDA BONNELL/RYERSON

THE CURRENT ENTRANCE TO THE FACTORY THEATRES STUDIO. FEB. 25, 2013 KAY BARRIE/FLICKR

AN OPEN SPACE IN THE THEATRE OFTEN USED FOR READINGS. AUG. 26, 2015 UNKNOWN/FACTORY THEATRE

THE ACTOR BARBRA GORDON SHOWS OFF THE NEW SITE OF FACTORY THEATRE IN 1984. FRANK LENNON/TORONTO STAR

NINA LEE AQUINO STANDS PROUDLY IN THE MIDDLE OF THE THEATRE. FEB. 28, 2021 PETER RIDDIHOUGH/SUPPLIED