[vc_row parallax_content=”parallax_content_value” fadeout_row=”fadeout_row_value”][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1555530030327{background-color: rgba(255,255,255,0.01) !important;*background-color: rgb(255,255,255) !important;}”][dropcap]The first thing that catches the eye upon arriving at Mother Earth Centre, an art space and a music store, is a remarkable pair of Nyabinghi drums placed next to a wondrous assemblage of drums, both broken and new. With upbeat red paint and shimmering metal screws, they are isolated from the others as if to confirm their rareness and perhaps a steep price tag. Out of curiosity, I asked the storeowner about the drums’ value. With a polite, yet startled expression on his face, he said they were his son’s childhood drums and weren’t available for sale.[/dropcap]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_widget_sidebar][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_column_text]Jahpaul Mohammed, the store owner, offered to show me some other intricately carved drums that were relinquished by their original owners. Jah, as he liked to be called, had dutifully repaired these drums and said he was willing to sell them to me at half the cost. Before I moved to Canada two years ago, playing my Yamaha guitar every day wasn’t just a passionate hobby but was also a quick way for me to de-stress from school homework. I found that musical gusto resurrected as Jah gave me a tour around his store. Given his self-proclamation as a Rastaman, a follower of the Rastafarian lifestyle -which was also apparent from his luscious twisted hair that the modern culture calls dreadlocks – I did not doubt his recommendation. Just like the dreadlocks, drums are an integral part of the Rasta culture and form the basis of its traditional cultural expression.

For Jah, his Mother Earth Centre is not merely an art space where he makes and repairs drums, sells art and gives history lessons to young school kids about the rich culture of Africa. It is his hope that the store will one day reconnect him with his own children. He doesn’t get to see them often after separating from his wife a few years ago. Mother Earth Centre is now also his home. In a mysteriously large room in the basement of the small, decrepit-looking structure of his store, Jah lives alone and is accompanied by hundreds of reggae and jazz music CDs. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_hoverbox image=”5799″ primary_title=”” hover_title=””]Broken drums pile up at Jah’s Mother Earth Centre on April 12, 2019. The artspace is also a popular spot among drum enthusiasts to get their musical equipment repaired and custom made. (RSJ/Abhi Raheja)[/vc_hoverbox][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_hoverbox image=”5970″ primary_title=”” hover_title=””]It takes great skill to repair a pair of drums. Jah fixes a drum with his bare hands and tries to find the key knot to loosen the ropes that hold the drum’s skin on April 12, 2019. (RSJ/Abhi Raheja)[/vc_hoverbox][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_hoverbox image=”5771″ primary_title=”” hover_title=””]Fixed and ready to go drums line up along the walls of Mother Earth Centre on April 12, 2019. Jahpaul is one of the few drum enthusiasts in Toronto who offer to repair broken drums. (RSJ/Abhi Raheja)[/vc_hoverbox][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_column_text]

[dropcap]On a recent Sunday morning in Toronto, Jah sat back in his chair and closed his eyes while removing his Rastacap, a crocheted round cap much like a tuque but larger, revealing his up-do dreadlocks. The cap is decorated with the Rasta colours: red, gold and green. These colours are adopted from the tricoloured flag of Ethiopia because of its incredible significance to the Rastafarian movement. Jah takes a deep breath before diving into the long-forgotten memories of his young adulthood. [/dropcap]

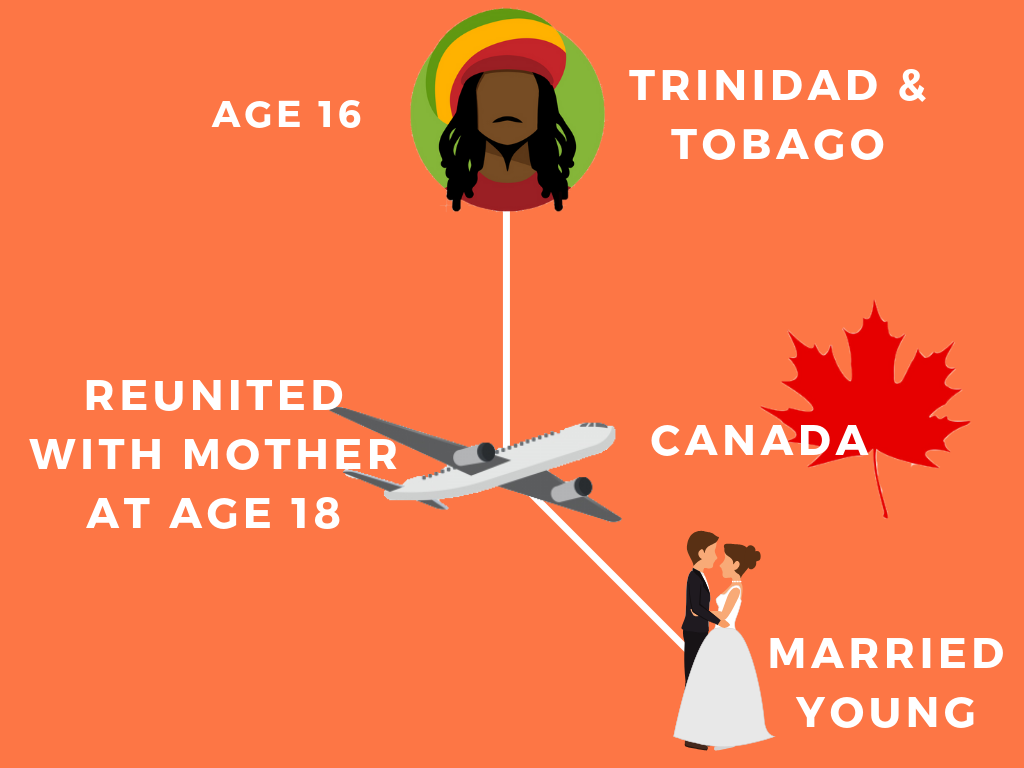

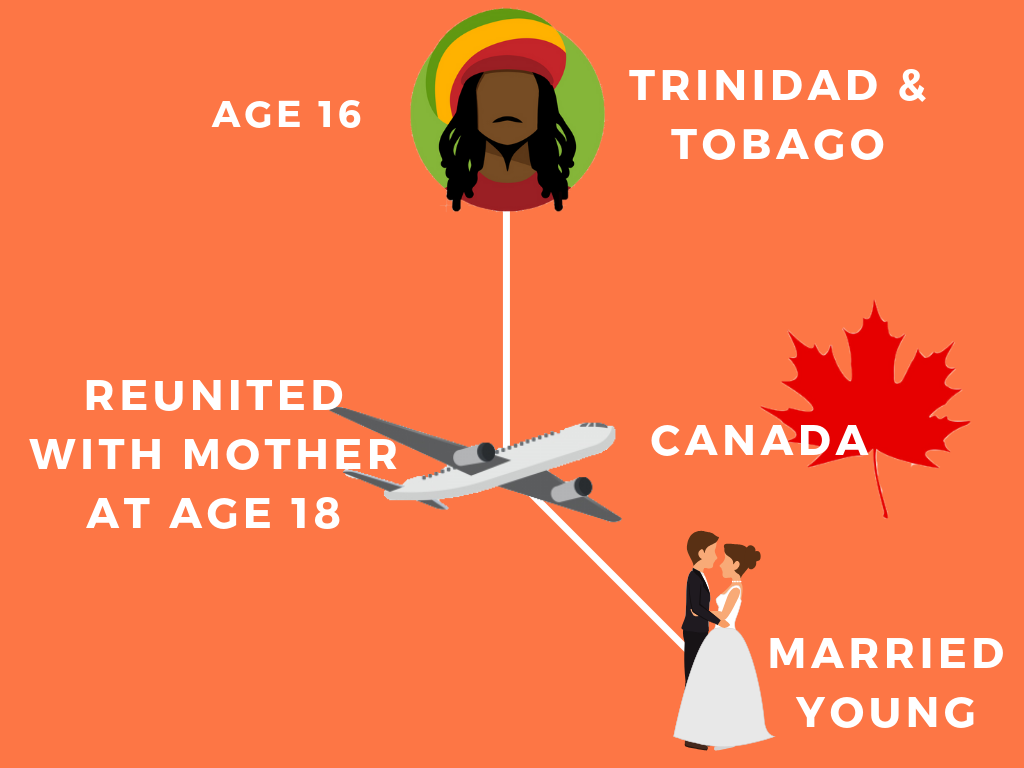

He did not want to come to Canada, but reminisces about experiencing two signs that told him it was the right thing to do. He was beginning to enjoy his hustle in his home village in the Trinidadian mountains of Diego Martin. He barely attended school as he spent most of his days with the Rastafarian community higher up in the mountains. Jah’s school visits were limited to supplying shipments of cigarettes and rolling papers, among many other things, at the Queen’s Royal College. His surreptitious actions had pushed him further away from his grandparents who had raised Jah in the absence of his mother. She worked in a hotel in the small town of Gravenhurst in Muskoka and had been long gone in pursuit of a better life for her children. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1554777748077{background-color: #ffffff !important;border-radius: 1px !important;}”]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_widget_sidebar][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_column_text]Jahpaul Mohammed, the store owner, offered to show me some other intricately carved drums that were relinquished by their original owners. Jah, as he liked to be called, had dutifully repaired these drums and said he was willing to sell them to me at half the cost. Before I moved to Canada two years ago, playing my Yamaha guitar every day wasn’t just a passionate hobby but was also a quick way for me to de-stress from school homework. I found that musical gusto resurrected as Jah gave me a tour around his store. Given his self-proclamation as a Rastaman, a follower of the Rastafarian lifestyle -which was also apparent from his luscious twisted hair that the modern culture calls dreadlocks – I did not doubt his recommendation. Just like the dreadlocks, drums are an integral part of the Rasta culture and form the basis of its traditional cultural expression.

For Jah, his Mother Earth Centre is not merely an art space where he makes and repairs drums, sells art and gives history lessons to young school kids about the rich culture of Africa. It is his hope that the store will one day reconnect him with his own children. He doesn’t get to see them often after separating from his wife a few years ago. Mother Earth Centre is now also his home. In a mysteriously large room in the basement of the small, decrepit-looking structure of his store, Jah lives alone and is accompanied by hundreds of reggae and jazz music CDs. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_hoverbox image=”5799″ primary_title=”” hover_title=””]Broken drums pile up at Jah’s Mother Earth Centre on April 12, 2019. The artspace is also a popular spot among drum enthusiasts to get their musical equipment repaired and custom made. (RSJ/Abhi Raheja)[/vc_hoverbox][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_hoverbox image=”5970″ primary_title=”” hover_title=””]It takes great skill to repair a pair of drums. Jah fixes a drum with his bare hands and tries to find the key knot to loosen the ropes that hold the drum’s skin on April 12, 2019. (RSJ/Abhi Raheja)[/vc_hoverbox][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_hoverbox image=”5771″ primary_title=”” hover_title=””]Fixed and ready to go drums line up along the walls of Mother Earth Centre on April 12, 2019. Jahpaul is one of the few drum enthusiasts in Toronto who offer to repair broken drums. (RSJ/Abhi Raheja)[/vc_hoverbox][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_column_text]

[dropcap]On a recent Sunday morning in Toronto, Jah sat back in his chair and closed his eyes while removing his Rastacap, a crocheted round cap much like a tuque but larger, revealing his up-do dreadlocks. The cap is decorated with the Rasta colours: red, gold and green. These colours are adopted from the tricoloured flag of Ethiopia because of its incredible significance to the Rastafarian movement. Jah takes a deep breath before diving into the long-forgotten memories of his young adulthood. [/dropcap]

He did not want to come to Canada, but reminisces about experiencing two signs that told him it was the right thing to do. He was beginning to enjoy his hustle in his home village in the Trinidadian mountains of Diego Martin. He barely attended school as he spent most of his days with the Rastafarian community higher up in the mountains. Jah’s school visits were limited to supplying shipments of cigarettes and rolling papers, among many other things, at the Queen’s Royal College. His surreptitious actions had pushed him further away from his grandparents who had raised Jah in the absence of his mother. She worked in a hotel in the small town of Gravenhurst in Muskoka and had been long gone in pursuit of a better life for her children. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1554777748077{background-color: #ffffff !important;border-radius: 1px !important;}”]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Jah’s first night in Canada was cold and he still seems to remember it vividly because that’s when the second sign appeared. He walked alone along the train tracks just outside Gravenhurst, still uncertain whether he had made the right decision, when a lush thick blanket of trees appeared to him with the Rasta colours of red, gold and green emanating from its leaves. In that moment, Jah knew, he was where he needed to be.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Jah’s first night in Canada was cold and he still seems to remember it vividly because that’s when the second sign appeared. He walked alone along the train tracks just outside Gravenhurst, still uncertain whether he had made the right decision, when a lush thick blanket of trees appeared to him with the Rasta colours of red, gold and green emanating from its leaves. In that moment, Jah knew, he was where he needed to be.

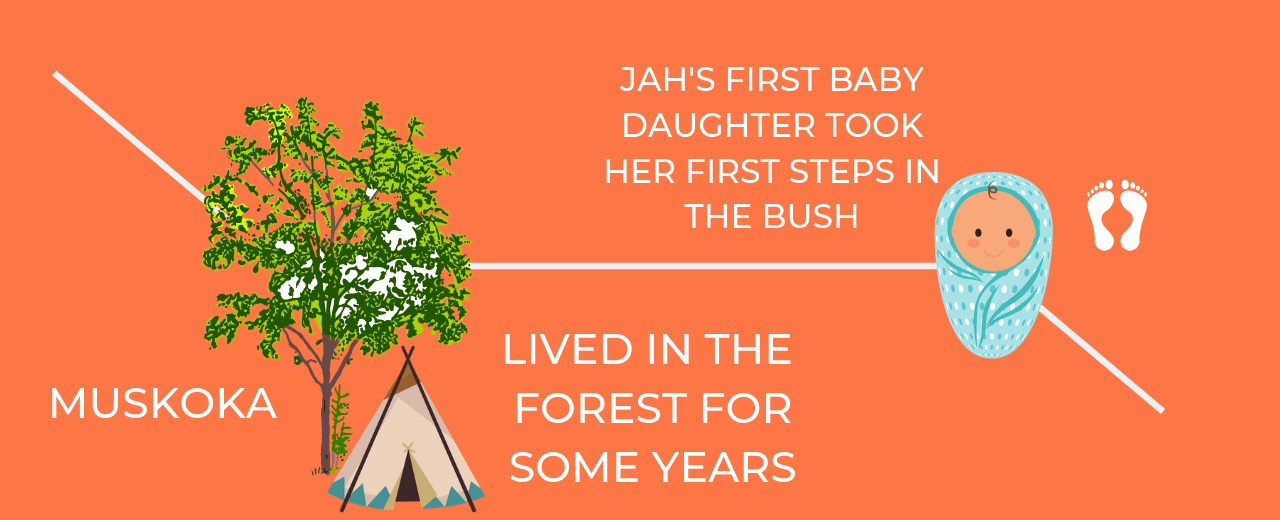

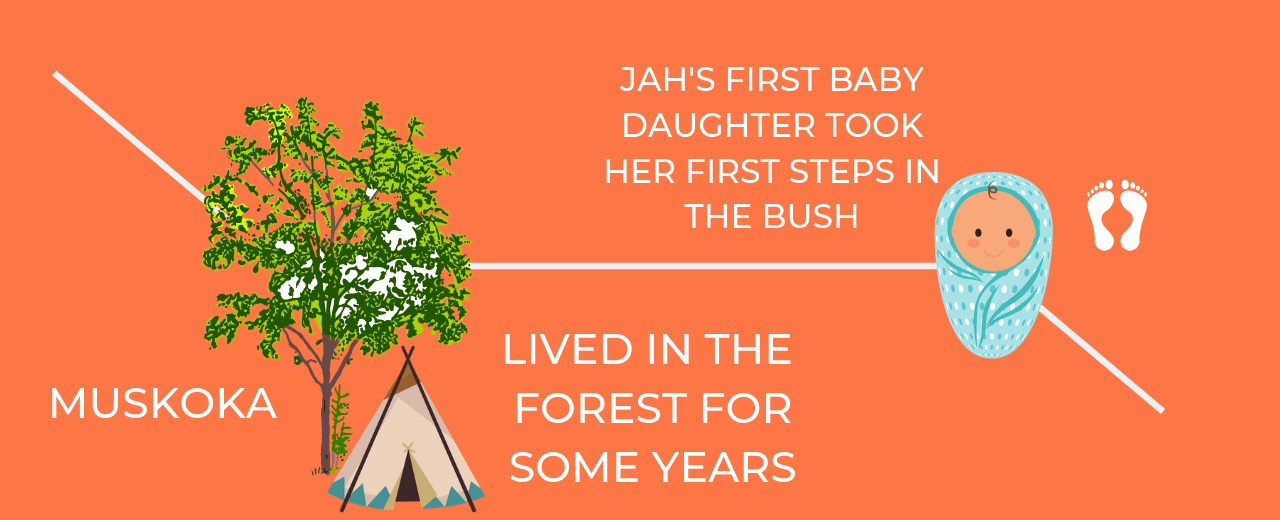

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Jah moved from another country, just like me, but his circumstances were entirely different. He quickly found comfort in his new home and met a girl while working at the Transformations Art Gallery. At 18, Jah married his first wife and decided to raise a family. But his love for nature would continue to unsettle him in the urban life of the town. The couple spent days, sometimes even months living in the thick of the forest up north. “Living in the bush,” as Jah calls it, is the only way for Rastafarians like him to connect with and be in total harmony with nature. He points to a photograph on his wall of memories. It’s a photo of his eldest daughter Aila. Jah tries to hide his smile as he recalls that it was in the bush where baby Aila took her first steps, but his eyes give it away. Jah and Aila’s mother appear to be celebrating ecstatically in the photograph as Aila learns to walk just outside the family’s tipi in the bush.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Jah moved from another country, just like me, but his circumstances were entirely different. He quickly found comfort in his new home and met a girl while working at the Transformations Art Gallery. At 18, Jah married his first wife and decided to raise a family. But his love for nature would continue to unsettle him in the urban life of the town. The couple spent days, sometimes even months living in the thick of the forest up north. “Living in the bush,” as Jah calls it, is the only way for Rastafarians like him to connect with and be in total harmony with nature. He points to a photograph on his wall of memories. It’s a photo of his eldest daughter Aila. Jah tries to hide his smile as he recalls that it was in the bush where baby Aila took her first steps, but his eyes give it away. Jah and Aila’s mother appear to be celebrating ecstatically in the photograph as Aila learns to walk just outside the family’s tipi in the bush.

Years passed and Jah moved to Toronto to find himself once again amidst the hustle-bustle of city life. As the 506 streetcar rumbles on the street just outside his store, he gets up to pick up his son’s drum that I inquired about earlier. I ask him whether he gets to see his children often, instantly regretting the question. Jah sips from his coffee, now probably cold, and remains silent. I know his silence means no. He occupies himself with history and drum lessons for young kids his children’s age, and finds his family in the Indigenous social circles where he is a popular musician. I ask him if he thinks his children will come to his store one day to meet him. He throws a smile at me; with his son’s drum still in his hands, he says, “Whenever they’re ready, I’ll be here.” [/vc_column_text]

Years passed and Jah moved to Toronto to find himself once again amidst the hustle-bustle of city life. As the 506 streetcar rumbles on the street just outside his store, he gets up to pick up his son’s drum that I inquired about earlier. I ask him whether he gets to see his children often, instantly regretting the question. Jah sips from his coffee, now probably cold, and remains silent. I know his silence means no. He occupies himself with history and drum lessons for young kids his children’s age, and finds his family in the Indigenous social circles where he is a popular musician. I ask him if he thinks his children will come to his store one day to meet him. He throws a smile at me; with his son’s drum still in his hands, he says, “Whenever they’re ready, I’ll be here.” [/vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_text_separator title=”Share Jah’s story with your friends”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_tweetmeme share_via=”xxtheglobetrotter”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_pinterest][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_facebook type=”button_count”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_text_separator title=”Share Jah’s story with your friends”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_tweetmeme share_via=”xxtheglobetrotter”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_pinterest][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_facebook type=”button_count”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Mother Earth Centre is an art space and a music store on Gerrard Street East in the Leslieville neighborhood of Toronto. On April 12, 2019 (Abhi Raheja/T·)

Audio clip of Jahpaul speaking about his journey to Canada and the signs that he appeared to him and convinced him that it was the right thing to do.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_column_text]It must have been 21 years ago now, Jah recalls, that the age of reason was dawning upon him and he was making big decisions. He couldn’t stay any longer in the perturbingly small three-room house that housed more people than it could fit. The grandparents occupied one room, all the male members of the family had another and the females claimed the last. One morning, as he made his way to his daily hike up to the hot water spring in the mountains, a voice spoke to Jah. “Those words have stuck with me and I can’t forget them,” he says. When Jah bathed in the spring, for the sake of mother nature, he would make use of the local Baccano tree leaves instead of soap. That day, some of this reddish-brown bush soap entered his eye and he couldn’t see anything. His vision was limited to a searing white-screen that bedazzled the back of his eyelids. The voice told Jah:[/vc_column_text][ultimate_fancytext strings_textspeed=”30″ strings_backspeed=”1″ strings_startdelay=”1000″ strings_backdelay=”500″ typewriter_cursor=”off” fancytext_strings=”“The road is rocky and steep, but it is the path that your heart must keep. Treacherous to him that fears, but glorious to the one that dares.”” strings_font_style=”font-style:italic;” strings_font_size=”desktop:50px;” fancytext_color=”#0c0c0c” strings_line_height=”desktop:70px;”][vc_column_text]He took the leap of faith and travelled to Canada to unite with his mother.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Jah’s journey from the mountains of Diego Martin in Trinidad to his own artspace in Toronto navigated on Google Earth Pro.” font_container=”tag:h1|font_size:20|text_align:center” google_fonts=”font_family:Alegreya%20Sans%20SC%3A100%2C100italic%2C300%2C300italic%2Cregular%2Citalic%2C500%2C500italic%2C700%2C700italic%2C800%2C800italic%2C900%2C900italic|font_style:100%20light%20italic%3A100%3Aitalic” css=”.vc_custom_1554766235199{background-color: #eeee22 !important;}”][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EkMzKnflTtA”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Jah’s first night in Canada was cold and he still seems to remember it vividly because that’s when the second sign appeared. He walked alone along the train tracks just outside Gravenhurst, still uncertain whether he had made the right decision, when a lush thick blanket of trees appeared to him with the Rasta colours of red, gold and green emanating from its leaves. In that moment, Jah knew, he was where he needed to be.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Jah’s first night in Canada was cold and he still seems to remember it vividly because that’s when the second sign appeared. He walked alone along the train tracks just outside Gravenhurst, still uncertain whether he had made the right decision, when a lush thick blanket of trees appeared to him with the Rasta colours of red, gold and green emanating from its leaves. In that moment, Jah knew, he was where he needed to be.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Jah moved from another country, just like me, but his circumstances were entirely different. He quickly found comfort in his new home and met a girl while working at the Transformations Art Gallery. At 18, Jah married his first wife and decided to raise a family. But his love for nature would continue to unsettle him in the urban life of the town. The couple spent days, sometimes even months living in the thick of the forest up north. “Living in the bush,” as Jah calls it, is the only way for Rastafarians like him to connect with and be in total harmony with nature. He points to a photograph on his wall of memories. It’s a photo of his eldest daughter Aila. Jah tries to hide his smile as he recalls that it was in the bush where baby Aila took her first steps, but his eyes give it away. Jah and Aila’s mother appear to be celebrating ecstatically in the photograph as Aila learns to walk just outside the family’s tipi in the bush.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Jah moved from another country, just like me, but his circumstances were entirely different. He quickly found comfort in his new home and met a girl while working at the Transformations Art Gallery. At 18, Jah married his first wife and decided to raise a family. But his love for nature would continue to unsettle him in the urban life of the town. The couple spent days, sometimes even months living in the thick of the forest up north. “Living in the bush,” as Jah calls it, is the only way for Rastafarians like him to connect with and be in total harmony with nature. He points to a photograph on his wall of memories. It’s a photo of his eldest daughter Aila. Jah tries to hide his smile as he recalls that it was in the bush where baby Aila took her first steps, but his eyes give it away. Jah and Aila’s mother appear to be celebrating ecstatically in the photograph as Aila learns to walk just outside the family’s tipi in the bush.

On April 12, 2019, Jahpaul practices on his favourite pair of drums before a performance at a local African cafè. (Abhi Raheja/T·)

[vc_zigzag el_border_width=”20″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]“Whenever they’re ready, I’ll be here.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_text_separator title=”Share Jah’s story with your friends”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_tweetmeme share_via=”xxtheglobetrotter”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_pinterest][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_facebook type=”button_count”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_text_separator title=”Share Jah’s story with your friends”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_tweetmeme share_via=”xxtheglobetrotter”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_pinterest][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_facebook type=”button_count”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Illustrations: VectorStock

[/vc_column_text][ultimate_heading main_heading=”Feature Video”][/ultimate_heading][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_column_text]Dancing Away the Loneliness Dance club for seniors at the Ralph Thornton Community Centre fosters togetherness The Seniors’ dance club at the Ralph Thornton Community Centre helps the elderly of East Chinatown feel a part of the community. The club has helped them escape issues like loneliness and gambling that have continued to affect families for decades. Below is a sneak-peak into the ballroom and line dancing lessons offered by the club for free.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/1BZjRY3dOEc”][/vc_column][/vc_row]