By Hyeji Yoon

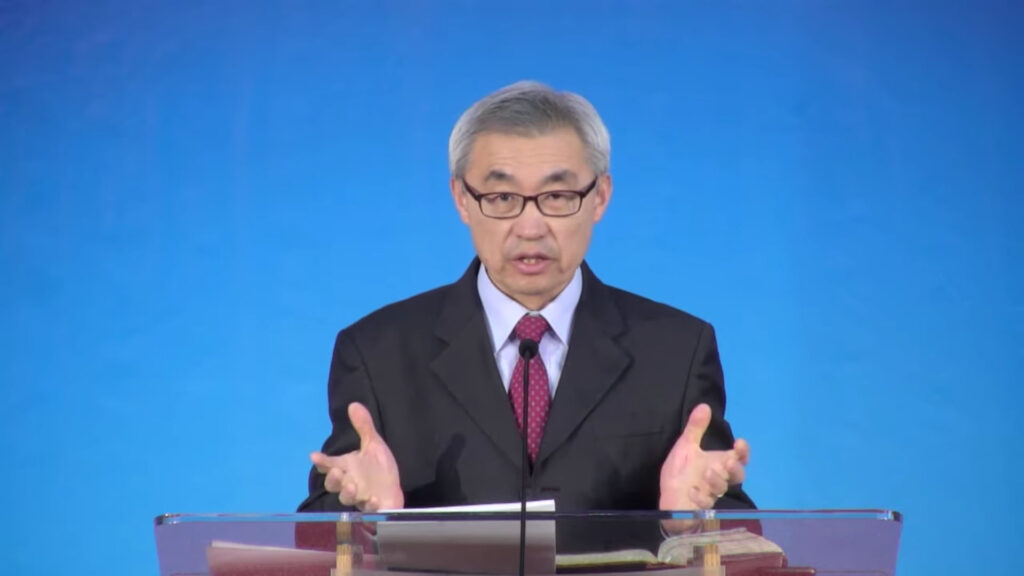

“To be honest, it’s not the best,” says pastor Minho Song, with the same candid manner he uses during his sermons. “I would go back to the old ways — no questions asked.”

He scratches the back of his greyed head, or maybe the nape of his neck. It’s hard to tell because two webcams with grainy quality and a pair of screens separate us. Though it may not be as good as “the old ways”, Song is used to this arrangement, because for the past year he has been pre-recording his weekly sermons for hundreds of his church members to watch on YouTube.

As the head pastor of Young Nak Presbyterian Church, Song has had a front-row seat to all of the changes and compromises its staff has made during that time.

Young Nak is situated in a half brown-brick, half sleek-white building in North York, Ont. It caters to Korean immigrants. Around half a dozen worship services are held every Sunday to accommodate the church’s four thousand registered members.

These days, to comply with public health guidelines on indoor gatherings, only ten people can enter the building at any given time.

Young Nak livestreamed its Sunday sermons near the beginning of the lockdown, when those limits were looser. Several dozen congregants were allowed to sit in the chapel, as long as they were socially distanced. One of the deacons placed stickers on the pews to designate where they could sit during the service.

“But, eventually we recorded [the sermons] because it’s safer,” Song says. Recorded sessions also mean that internet connectivity issues are not as much of a problem.

Song and the tech crew film his sermon for the Korean-speaking members on Saturday mornings. In the afternoon, pastor Timothy Song (no relation) records a praise-music performance with volunteer musicians for the English-speaking members. The main chapel where they both film is thoroughly sanitized after each session.

While both pastors say that they’ve managed to adapt to these new rules, they’re still having trouble with the fact that they cannot preach or worship God to a live, present audience.

“I am preaching to an empty crowd,” says Minho. “Sometimes, you need the response from the people, then you get more excited. That’s completely not there.”

He says several times during the interview that one of the biggest losses during the pandemic is the sense of community. After Sunday service, dozens of people would line up for three-dollar lunches at Young Nak’s basement cafeteria, then grab a seat with their friends — either in the cafeteria proper or the child-sized pews scattered throughout the building. Connecting with other people was as easy as talking to the people around you between mouthfuls of soup, rice, and kimchi. That simply won’t be possible for the foreseeable future.

Pastor Tim has another concern: that people are becoming too comfortable with the new way of life. “Imagine sitting on the couch, worshipping. In the same place, you probably spend hours watching Netflix. I think that really affects you spiritually.”

Moving Sunday worship online means that people now have a reason — and are encouraged, even — to worship God in the “relaxing, unchallenging environment” of their own homes, according to him.

Teens, as they gradually gain independence and grow into young adults, are a particular concern in this area. According to the Pew Research Center, Christianity has declined in popularity in Canada over the past few decades. A 2011 survey from them shows that 29 per cent of Canadians born in the ’90s are disaffiliated with religion altogether. Both Tim and Minho Song are worried that the continued lockdowns will only make these numbers worse.

The teens who attend Young Nak have had to endure two semesters of Zoom classes in school — another online commitment could turn them off from church altogether. As the head of Young Nak’s English-speaking youth division, named Delta, it’s the job of Ron Kwon and his ten-person team to figure out new ways to keep the kids engaged in their faith.

“I think we’ve tried everything under the sun,” he says. He laughs, but as he lists the ideas implemented during the past year, it’s obvious that the statement itself is serious. To name a few, they’ve tried online Bible studies, Christian book studies, and a monthly podcast (named the “Delta Godcast”). Last June, they hosted a parking lot Sunday service at the front of the church building.

The newest initiative is an online group chat on a client called Discord, which teens can use to talk with other churchgoers. In the few weeks since its formation, members have used its functions to play games with each other like Minecraft. Each Sunday at 9 a.m., a handful of them enter a voice chat and watch the week’s Sunday service as it first airs.

Both the parking lot service and the Discord chat server did what they were supposed to do, but the problem is that engagement and interest always drop after a period of time. The lockdown has just dragged on too long, for both the leaders and the followers.

Pastor Tim Song lets out a sigh as he remembers first adjusting to the COVID-19 protocols last March. “I was very ignorant. I thought maybe, two weeks, and we’d be back for Easter,” he says. Only after a few months did he commit to a proper office space in his house by moving his bedroom furniture around.

“It’s taking too long,” mourns pastor Minho Song. There’s been a firm edge to his voice throughout the interview, one that sounds tired from a year of empty pews and hosting funerals. He’s worried that Toronto will take at least another year to “go back to normal” — and, he adds, how many people will be left to enjoy that normalcy by then?