By Daniella Lopez

As the referee hands the basketball to Kyle Lowry, he faces a challenging task: in five seconds or less, he must find a teammate to throw the ball to or else the Toronto Raptors will lose their third straight game against the Boston Celtics in a best-of-seven series. The problem? Six-footed Lowry is guarded by seven-foot-five Tacko Fall and there’s only half a second left in the game.

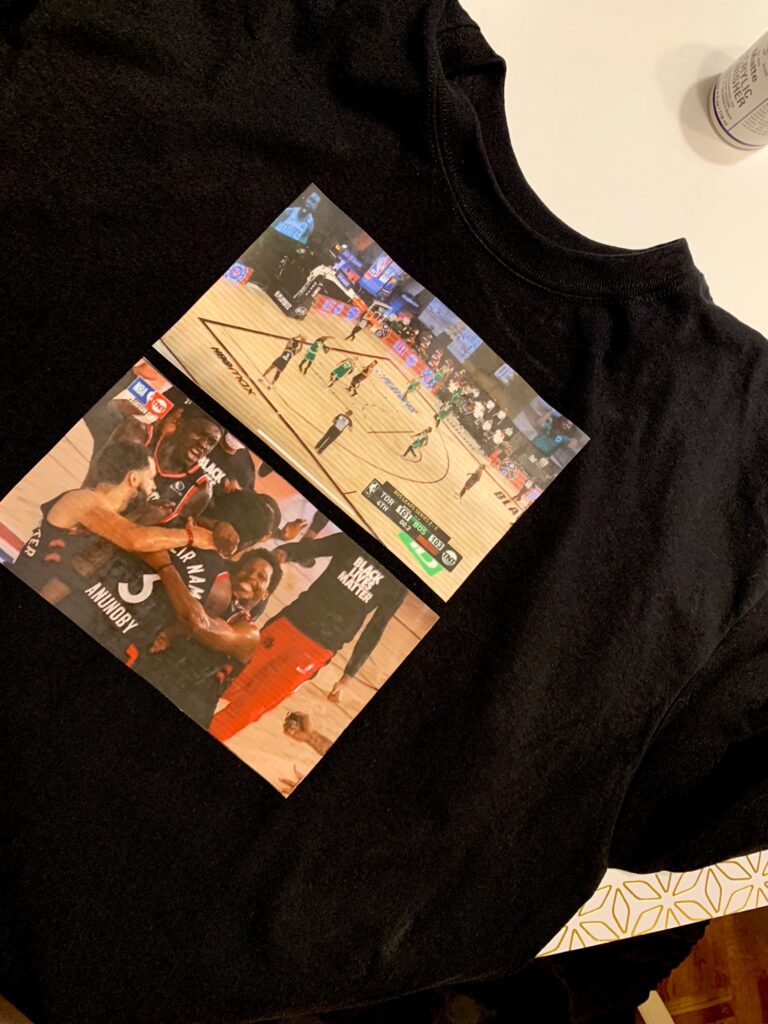

Lowry throws the ball approximately 50 feet over Fall’s head. With the ball landing in OG Anunoby’s hands, there’s only one thing to do: shoot. With no hesitation, the ball soars out of Anunoby’s hands just as fast as it got there; the buzzer sounds before the ball hits the rim and falls into the hoop. The Raptors have just won a game against the Celtics in the NBA’s 2020 Eastern Conference semifinals.

Like any other fan, Melissa Gil shares her excitement about what she just watched on Twitter with her thousands of followers. Melissa, or Mel as she likes to be called, later posts a picture with the now-famous shot plastered on a T-shirt. While most fans would be celebrated for posting something similar, for someone like Mel—a female fan of the Raptors—the reaction is quite different; within days, she receives an image of severed body parts with the words “this will be you and your family.”

Although this wasn’t the only feedback she received that day, this kind of reaction is common for female fans who support the team. As women become more vocal on Raptors Twitter—a group of Raptors fans that share their opinions about the team on the social media app—more and more of them deal with online harassment every day.

Mel didn’t purposefully use Twitter to connect with other fans. As she remembers, it just kind of happened. After creating an account for the sole purpose of NBA All-Star Voting, she eventually became more involved in the fanbase. She followed a few people herself, then a few more until she herself had grown a following.

“It was kind of traumatic, at first,” she says of the incident. She felt scared and confused: was this person serious or joking? Besides the death threat, she also received messages from people threatening to sexually assault her. “What do you get out of saying that?” she wonders.

The mistreatment of women in these spaces isn’t a coincidence, according to Alison Harvey, an assistant professor of communications at York University. Sports spaces are more widely associated with a “homosocial masculine domain,” she says, which are social interactions related to men. According to a Nielsen study, 38 per cent of men worldwide are interested in the NBA, 10 per cent higher than the number of women.

Since that fateful comment, Mel hasn’t received anything quite that shocking. She credits the “good people” on the app for supporting her when similar situations arise. “[They] really help make you forget about all the negativity.” Now that she has a substantial following, Mel feels an obligation to continue using the app as a content creator and a sports media student.

“What do you get out of saying that?”

Melissa Gil

It’s not just sports spaces where women face harassment; altogether, women are disproportionately affected by online harassment. Women are 27 times more likely to be harassed online than men, according to the 2017 European Women’s Lobby report.

Like Mel, Siera is a fan of the Raptors, though she believes she joined Twitter later than most fans. After the Raptors won their first championship in 2019, she noticed the growing fanbase and wanted to find a space to connect with other fans.

Siera remembers her first experience with harassment on the app clearly. Circulating within the space was an ongoing debate about whether the team should trade for a particular player, James Harden. Siera, among many fans, was against the trade and actively voiced her opinion on her account. She recalls those wanting to trade for Harden would respectfully disagree with others who had differing views, but they would harass her for her opinion.

“Go back to the kitchen.”

“You shouldn’t talk sports.”

“This is why I don’t trust women’s opinions.” These were the common insults she saw.

“Experiencing that sexism is really discouraging,” Siera says. “It makes you not want to share your opinions because you’re worried that you’re going to get that harassment.”

The abuse only escalated from there. Siera believes the initial taunting made her a target for more. Her direct messages were flooded with people questioning her basketball expertise when something she tweeted was incorrect. Meanwhile, Twitter accounts would appear from nowhere to make fun of her appearance; more showed up when she blocked them.

“It definitely took a toll on my mental health, and it took a toll on my ability to enjoy basketball and speak about basketball freely,” she says, “It makes you feel like there’s no room in that space for you.”

Initially, she ignored the messages or tweets directed at her, but it got worse. Siera felt like she couldn’t escape. Eventually, she shared the harassment she faced with her followers. In calling out her harassers, others around her were aware of the situation and defended or supported her.

“The more I call it out, it seems to go away,” she said.

While Siera and Mel experienced harassment with thousands of followers, Crina Mustafa experienced cyberbullying with a much smaller audience.

With a follower count coming in between 100 and 200, Crina thought posting an opinion on Twitter was harmless. Then she received her first death threat. Scared and unable to sleep, the threat deeply affected her, especially as a 16-year-old high school student.

“It makes you feel like there’s no room in that space for you.”

Siera

“I wasn’t grown enough to realize that if I just blocked the person, it would be OK,” Crina says.

A friend told her to reach out to other women on Raptors Twitter. With their lessons and support, Crina learned about the realities of harassment of women in male-dominated spaces; it’s still a common occurrence, but she says blocking them and moving on is the easiest solution.

While cyberbullying can have legal consequences in Canada, criminal charges can only be laid if the harasser commits offences under Canada’s Criminal Code. This forces victims to act on their own accord, often by blocking accounts or calling out their harassers.

Crina officially made a Twitter account in October of 2018 to keep up with sports news. Initially, she wanted to turn off her direct messages at 1000 followers. However, before she reached that milestone, she turned them off. “[The harassment] got so bad that when I got to 500, I turned them off.”

Once she gained more control of her experience, Raptors Twitter became a community for Crina, one filled with women and non-binary folks to discuss their love for the team. The safe space became part of her life, from the active group chats to the occasional Zoom meetings. She found a family of people who supported and stood up for her, because they, too, understood the reality of being a woman online.

For many Raptors fans, Anunoby’s high-pressure shot will be remembered as a moment of joy. While Mel will remember that initial feeling of excitement, she’ll also remember the harassment she received for tweeting something seemingly light-hearted, the constant fear of violence against her, or even worse, her family.

Anunoby had less than a second to alter the Raptors fate. It takes less than a second to alter someone’s experience on Twitter as well.