By Vanessa Pellegrini

Zachat Ochalefu, a fashion student at Toronto Metropolitan University decided to take a walk at the Eaton Centre as a result of being stressed out from a bad day. She happened to see a large sign outside of H&M that reads “50 per cent off the entire store including sustainable items.” This sign caught Ochalefu’s attention and encouraged her to enter the store rather than window shop. As she started to browse through the clothing racks in the store, she mysteriously ended up in the changeroom trying on a bunch of different outfits for nothing in particular.

But is it enough to get an amazing discount on a large amount of clothing? Most consumers will usually just purchase clothing from stores like H&M without knowing what textiles were used to actually produce the item. Little do they know: with every purchase, it takes a toll on the environment.

According to the City of Toronto’s Textile to Waste Diversion and Reduction Initiatives Report, in Toronto alone, 37.7 per cent of residents either throw their clothes in the garbage or recycle them. Although consumers are looking for disposable outfits daily, less than one per cent of recycled clothing is actually produced to make new items.

Fast fashion is currently affecting Toronto due to the rise of inflation and population, the negative impact of delivery, and the marketing tactics of greenwashing. But do we even know if clothing that is marked as ethically sourced is actually ethical? And is sustainable fashion actually sustainable?

Due to high demand, companies are mass producing these so-called high fashion designs into capsule collections, which are replicating recent catwalk trends and pricing these pieces at a low cost to move them quickly into retail stores. Even though fast fashion manufacturers are located overseas, which brings down prices, the cost of rent and groceries is causing consumers, including students, to purchase from fast fashion brands to make it more attainable.

When I talked to Daniel Drak, a fashion professor who taught at TMU but is currently at the New School in New York City, he said when it comes to environmental issues in the fashion industry, Toronto needs to consider economic, social, political and educational factors. When I paused and asked “is there anything else?” Drak laughed and replied, “we are just getting started.”

One issue that really bothers Drak is how the fashion industry disproportionately impacts overpopulated city centers like the GTA due to heavy consumption and the immense constant turnover.

According to Drak, the accumulation of microplastics, the extensive use of indigo dyes and acid treatments have a negative impact on the ecological system in Toronto due to the high volume of consumers that are ordering online in large quantities from brands like Shein that have poor packaging and long transportation times. Drak wasn’t the only one with these convictions, as other community members also feel these concerns will lead to ongoing sustainability issues in Toronto.

Thomas Hart, a philosophy professor at TMU, said online fast fashion brands view Toronto as an easy market because they do not consider the local reality after selling the products as the clothes are going straight into the landfills.

Camille McConkey, a fashion student in the graduate program at TMU, said fast fashion brands flock to the city of Toronto because it is fast paced, and a lot of people adopt that mentality when purchasing clothing items.

McConkey sometimes follows that mentality of purchasing fast fashion as costs are tight due to her master’s program and living in Toronto. However, she purchases in small quantities or tries her best to avoid it altogether.

It’s an approach familiar to Ochalefu. When she moved from Nigeria to Toronto in August she noticed the cost of living is expensive, so she understands why people will opt for cheaper garments.

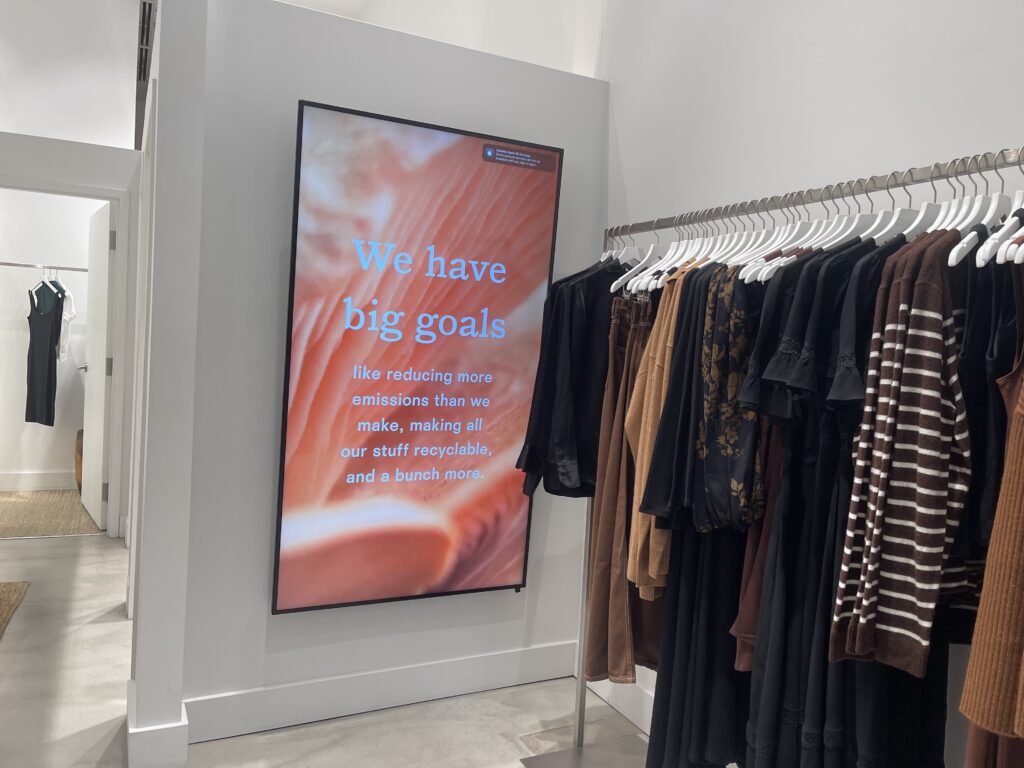

Complicating the situation is the phenomenon of “greenwashing,” where brands convince consumers that their products are environmentally friendly when they are in fact not. Drak said it is a function of marketing, as brands will market fashion as something that is trendy to consumers who are calling for green fashion and those calls are being listened to by businesses.

“Because of this trend of environmental awareness and sustainability, companies are capitalizing on this to make profit,” Ochalefu said. “It is unfair to take advantage of the people who actually want to make a change and improve their spending habits.”

Fast fashion companies know consumers don’t pay attention, so they have the upper hand by conveying a message with the perception of greatness.

“Greenwashing is very manipulative and kind of evil,” Drak said. “Tapping into the desire that there is less of an impact in this kind of consumption which increases skepticism around this sort of green movement.”

He said we cannot trust businesses to do what’s right for people and the planet. “I believe in government intervention rather than the free market which is very much the American way,” said Drak.

As fast fashion companies continue to maximize profits, Hart recommends that the GTA should focus on corporate social responsibility as self-regulation. In order to contribute to societal and environmental goals, he said it is important to optimize the amount of waste produced and utilize wearable materials.

“Brands like Patagonia will take the product you purchased that started to wear out and repair it,” Hart said. “This increases longevity and demonstrates corporate responsibility, which is a sustainability factor the GTA needs to start taking seriously.”

To think about impact instead of profit margins, Hart suggests that labelling and information transparency is something the city of Toronto can control by making it clear that the fast fashion industry cannot get away with cheap labour in developing nations.

Drak said brands are intuitive in the way they capitalize on how students are easily drawn to the latest fashion trends by just scrolling through social media, which is a prominent issue that takes place in Hart’s teenage daughters’ lives.

“My daughters do not all look at the same social media but whatever they buy all has a brief desirability life,” Hart said. “I want my daughters and my students to understand that this is paid advertising and they should look for the equivalent at secondhand shops.”

Hart supports vintage designer clothing businesses like Just Thrift as they help reduce the carbon footprint because the clothing is locally sourced and will not be transported overseas.

Drak encourages consumers to support the small label designers but advises that sustainable stores can greenwash too. The local brand Kotn claims they are maintaining environmental transparency by persuading the public that they are timeless by their choice of natural fibers and packaging practices.

Since sustainable stores are attempting to follow a limited product offering, McConkey suggests fast fashion brands should try to replicate this guideline as it will help the environment.

“Instead of purchasing and disposing at a rapid rate, focus on a consistent purchasing behaviour,” McConkey said. “I feel like this will be a bit controversial, but society needs to move away from such a growth mindset.”

Hart also agrees with focusing on consistent purchasing habits as he advises that there is a platonic form with sustainability. “We have to do as much as we can with less and that will bring about conscious change.”

But how do we force stop traditional shopping habits? “How do we make the invisible, visible?” Drak said a key piece is education because formal institutions like TMU have the power to change the conversations by informing students to make ethical decisions when purchasing clothing.