By Josh Jackson

Listen to this article

A crowd forms around the bartender, who frantically mixes cocktails and cracks open cold bottles of beer. Pop songs blare from the speakers above, pulsing through the place like the palpable anticipation for the night ahead. A disco ball casts shimmers of silver light across the dimly lit room full of women, femme and gender non-conforming revellers. A few men and masc-presenting individuals dot the room, but they are far outnumbered. As lively as the scene is inside, Parkdale’s recent addition to the outer edge of a historically queer-friendly neighbourhood isn’t easy to spot. The storefront is narrow and, with minimal signage, you might walk right past it. There are no rainbow flags, just a simple “Three Dollar Bill” in green cursive writing on the large storefront window. That name, though, is as queer and unique as the individuals it welcomes.

It’s part of a new crop of bars popping up in Toronto’s west end, which – with names like Peaches Sports Bar, Tammy’s Wine Bar and the aforementioned Three Dollar Bill – are physical manifestations of an evolving community. The owners are catering to those who don’t fit the firm binaries of gender or sexuality and aiming to reimagine what was lost in the past decade when neighbourhood staples such as The Beaver closed their doors. In doing so, they hope to bridge the gap between binary understandings of what it means to be queer and femme.

“There’s a culture shift that’s happening… Women are shifting the power dynamic a little bit,” said Ronnie Saye, the co-owner of Peaches Sports Bar, a two-minute walk from Three Dollar Bill. The storefront of Peaches, previously called Tennessee Tavern, is wide and painted bright orange. The name hangs above the front door, which features the logo – a red baseball shaped like a heart. Saye and longtime friend Anthony Fushell opened the bar in 2023 and named it to recognize the legacy of the Rockford Peaches, an all-female professional baseball team from the 1940s made famous in the movie A League of Their Own. The plan was to create both a shrine to sports and a sense of belonging for a more diverse crowd.

“I just never found somewhere where I felt community in that sort of sports area, and I just feel very fortunate to offer that to people,” said the green-eyed Saye, who has shoulder-length black hair and a sleeve of colourful tattoos.

Nearly an hour east by public transit, it’s hard to miss the stretch of Church Street in the heart of Toronto’s historic Gay Village, where rainbow colours adorn street lamps, crosswalks, and business windows. The Village is busiest on weekend nights, when groups of men line the streets. Conversation and cigarette smoke converge in the air as drag queens carry suitcases in and out of clubs packed tightly together. All-business names like Woody’s and Men’s Room make it known who these spaces are for before even entering the bars, where men are the overwhelming majority.

Saye first snuck into bars there some 20 years ago with her gay brother, in what she now describes as her “baby gayness” period. Here, she would have her first exposure to the world of gay nightlife that had existed for decades by then, always in the company of men.

The desire to be seen and heard didn’t end with The Gay Liberation Movement of the 1970s, though. Decades later, alternative queer identities are beginning to break through in popular culture, with TV shows like Sex Education, challenging labels and one-size-fits-all approaches to gender and sexuality. This media representation and a more accepting political climate in some parts of North America have also made coming out feel less anxiety-ridden, and more people are openly identifying as non-heterosexual. The economics of nightlife appear to be changing, too. Traditionally, gay bars catered to those who had the most money to spend on a night out, according to Marty Fink, an associate professor in professional communications at Toronto Metropolitan University whose area of focus is queer and trans studies.

“Public spaces historically haven’t been set up for women to participate, or for trans people, or for non-binary people to feel safe or comfortable,” he said. “Even straight women don’t have their own bars to hang out.”

Saye remembers venturing out of The Village and discovering The Beaver, a queer bar that opened in 2006 and was a fixture in Toronto’s west end for 14 years. It opened the gates of imagination that queer nightlife didn’t have to be dominated by gay men, she said, recognizing that it was her first experience being surrounded by queer women while simultaneously “realizing that there was a huge lack of [this alternative].” The Beaver closed in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, part of a wave of openings and closings in the neighbourhood over the past 10 years that included Slack’s, The Henhouse, and Less Bar.

Some were open for several years, others only for a few months. Some, by design or intention, catered largely to a lesbian crowd. When Slack’s closed in 2013 after a handful of iterations since its opening in 1997, original operator Heather Mackenzie told Xtra Magazine that times were changing, with “the need for an exclusive women’s bar… slowly declining.” Mackenzie also suggested to the magazine that it was a tougher slog to find a uniform way to serve them, with parties around the city catering “to all different types of women.”

Perhaps in recognition of this, the owners of Three Dollar Bill and Peaches, whose cheeky name also winks to evolving personal identities, are planning to work together on an alternative Pride Month celebration: less corporate, and more goofy. A drag queen dunk tank is one of the ideas in the works.

Three Dollar Bill’s website declares the bar to be queer-owned and operated and makes the mission known: to build community and create a space to explore personal identities and make lasting connections. The co-owners Castle, Meaghan and Maro set the stage by using only their single, chosen names.

“You can say tomorrow, ‘I identify as this,’ and the next time I see you in the bar you could say ‘I identify as that,’ and I’d be, like okay cool, as long as everyone’s happy,” said Castle. A carpenter by training, the co-owner said trying to build something that will last where so many queer-friendly spaces have disappeared adds a bit of weight to their efforts.

“At times it does feel like it’s a huge responsibility,” Castle said. “Like we’re literally the undertaking for a full community.”

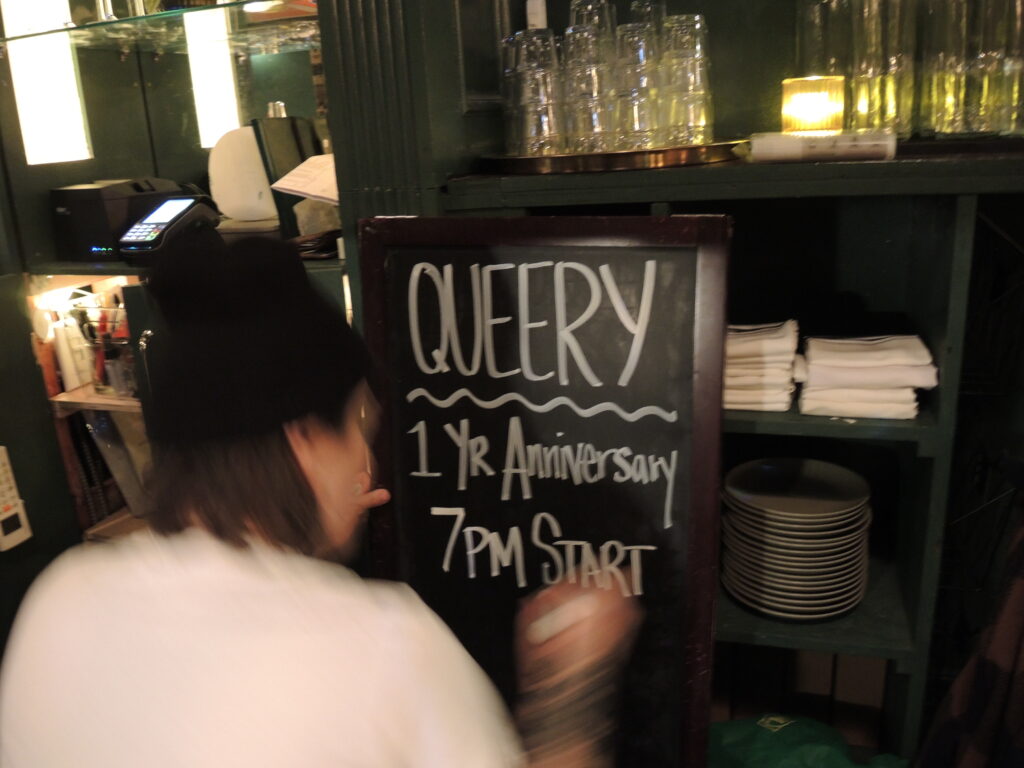

On a recent Wednesday, the bar packed in a crowd for a trivia night called “Queery.” The place was so crammed a half-hour before quiz time, it seemed like it could not hold another person, but that didn’t stop enthusiasts from squeezing through the door and wedging themselves around the bar.

At 7 p.m., though, the hosts had to ask people to leave as they were over licensed capacity. The contest that night ends in a tie, broken by a final question: Who can come closest to guessing the birth date of Australian actor Jacob Elordi – one of the young stars of acclaimed queer thriller Saltburn. After the teams cast their guesses and the two non-binary hosts, Reins and Izzy, reveal the winner, cheers and laughter can be heard throughout the bar. “No one’s taking themselves too seriously… we’re here to have fun,” Castle said earlier that day while walking through the empty space hours before opening.

Looking out at a sea of queer-femme and nonbinary people who showed up for Queery, it’s clear there’s demand – and community – here. The bar’s Instagram account has amassed more than 8,000 followers since the bar opened in October of 2023, and there’s a constant buzz one of the three co-owners, Meaghan, described as “queer joy.”

Kelsey Cloutier, a queer tattoo artist with a shag haircut and sleeve of tattoos, comes here often with a group of friends for the trivia event every other Wednesday. On this particular hump day, she sat at the bar and explained the draw. “These are my people,” Cloutier said. “I can do anything and be anything here.”