By William Dixon

Uniformed students from MacLachlan College funnel into the silent auditorium as a frail, diminutive 94-year-old shuffles to her seat. She is perched on a petite, old wooden chair, nodding to the students as they file in one-by-one and sit down around her. The room hums with whispers from the students. “Shhh,” one says, the presentation is about to begin.

“Hello, my name is Vera Schiff and I am a Holocaust survivor.”

The Sarah and Chaim Neuberger Holocaust Education Centre was officially opened in 1985. The centre provides education and understanding about the Holocaust and serves as a platform for dialogue about civil society for present and future generations.

Michelle Fishman is the manager of education, outreach and communications at the centre and the granddaughter of four Holocaust survivors. Fishman works with survivors daily and assists with programs that teach subsequent generations about Holocaust history, its lessons and legacy.

Fishman says the centre reaches an average of 50,000 people annually through school visits and its signature education programs such as In Conversation and Holocaust Education Week. In Conversation brings schools and community groups to hear survivors tell their story and create a personal connection to history.

Schiff is one of the centre’s most notable survivor speakers and has been conducting presentations for over 10 years.

It’s Prague, 1939. Dinner has just finished, and a young Vera Schiff sits on the lap of her father, Siegfried Katz-Taussig, as her mother, Elsa, cleans up. Vera’s older sister, Eva, is somewhere in the house. Eva is always doing something, Vera recalls, whether it’s lending a helping hand or coming up with games for them to play. She is so full of energy, so full of life.

The night grows older and the family begins to settle down. It is a night like any other and 12-year-old Vera decides to sneak out and have some fun.

She walks to the street, turns the corner and stops. Uniformed soldiers with machine-guns stomp down the street. Scared, shocked and confused Vera runs home, up the stairs and into her bed. This is the first time she has seen a Nazi. On this night, childhood for Vera comes to an end.

In the following days, all the Jews are rounded up and put into make-shift ghettos around the city of Prague. Life for them is never the same.

Coupled with Schiff’s presentation is a tour conducted by one of the centre’s expert educators and volunteers, like Joyce Rifkind. On an unseasonably warm February morning, she guides students through the centre’s library and then to the auditorium, offering insight about life before, during and after the Holocaust.

Rifkind stops at the large, green brass doors of the auditorium, and asks the gossiping students if they recognize either of the two symbols on the door (שש). One student, who clearly knows his Hebrew, says it looks like “shesh,” which is 6. Another suggests it looks like two trees. Somewhat surprised, Rifkind tells the students they are both correct.

The number 6 represents the 6 million Jews who died during the Holocaust. The artist elongated the Hebrew letters to create two trees, which Rifkind says is symbolic of the rebirth of Jewish culture and people here in Canada.

She pushes the heavy doors forward and ambles down the hall of the auditorium, the students following her. Enveloped by pictures of survivors and Holocaust artifacts, the once loud-laughing group of students now falls silent, as if someone had sucked all the air out of the room.

after her presentation at the centre on Feb. 7, 2020. (William Dixon/T•)

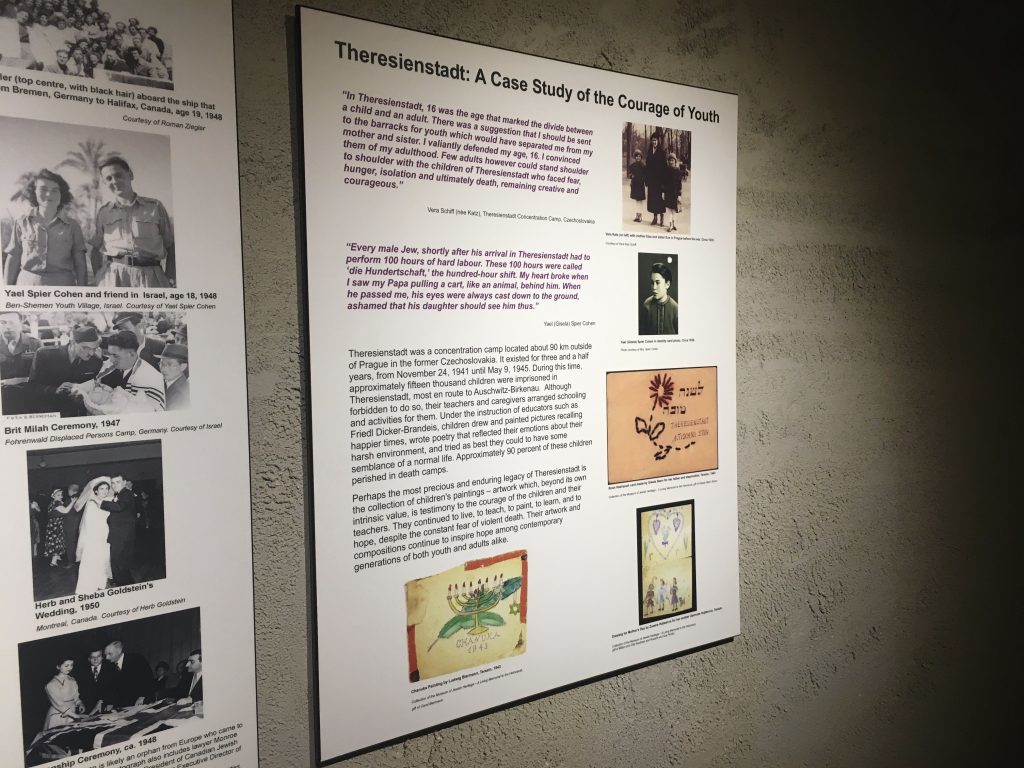

In May 1942, Schiff and her family, including her mother, father, sister and grandmother are deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp.

After the two-hour train from Prague to Theresienstadt, the Katz-Taussig family are separated by gender. Although Schiff doesn’t know it, this is the last time she ever will see her father.

What were once an army barracks and horse stables are now overflowing with thousands of old, dirty cots. The claustrophobic quarters are a breeding ground for lice, parasites and viruses. Schiff recalls that on more than one occasion she woke up, startled, by a rat in her bed gnawing at her toes or ears.

Schiff is assigned to work in the camp’s hospital – “Vrchlabi” – while the rest of her family are sent to work in the fields. She still doesn’t know if it was a blessing or a curse. On one hand it allows her to avoid the ongoing deportation to the death camps while on the other, it forces her to watch as each of her family members died.

Her sister Eva, once a vibrant energetic little thing, contracts strep throat (even then a curable illness with proper medication and care) and over the next couple weeks Schiff watches as her sister – her best friend, her confidante – slowly withers away.

Starvation and fear of death are a constant in Theresienstadt. On a spring morning, Schiff remembers, a prisoner who looks more like a skeleton than a young boy, climbs a cherry tree to get some fruit. Before he can pop the delicious fruit into his mouth an SS soldier walks over to the boy, pulls out his pistol and shoots him in the head.

Such atrocities happened daily, Schiff says. People would be hanged or shot for the smallest misdemeanors. She can’t even count the number of executions she witnessed at Theresienstadt. Even one was too many.

But there was some joy amid all the suffering. She met her husband, Arthur Schiff, in Theresienstadt. A gentle and handsome man, it was his kindness that she really fell in love with, says Schiff. In the concentration camp, kindness was even more scarce than food.

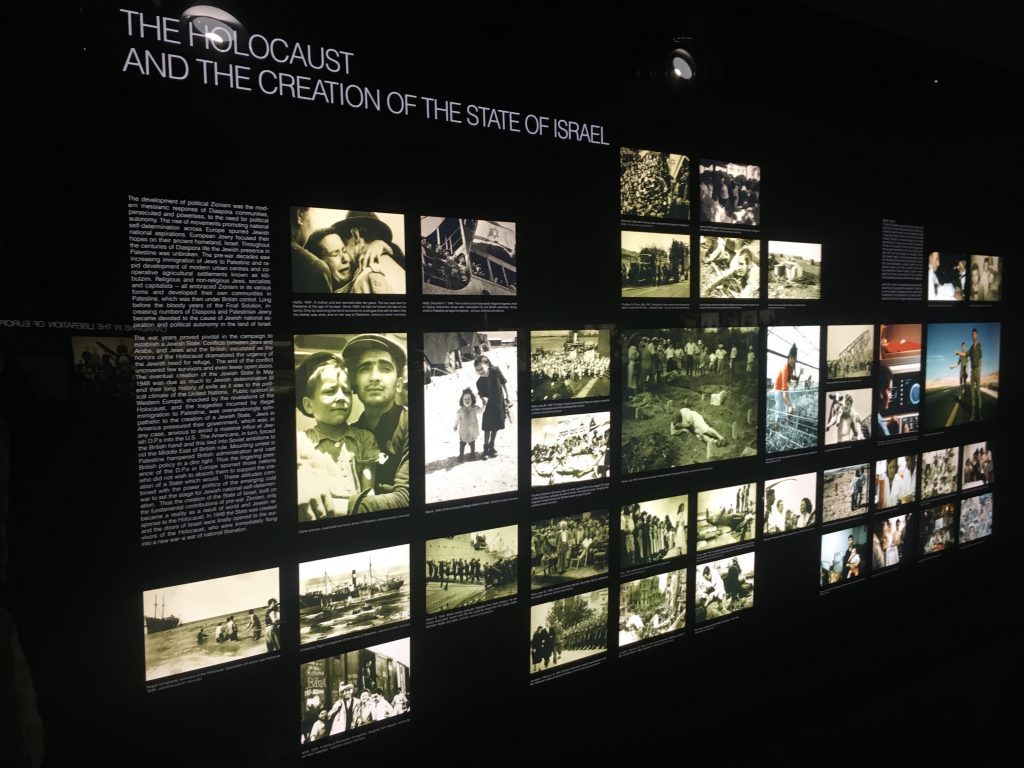

On May 8, 1945, Theresienstadt was liberated by the Russian Army. Following the war, the couple returned to Prague. Then, in 1949, they made “Aliyah” (the term for the immigration of Jews from the diaspora to the Land of Israel) and lived in Israel until 1961. Arthur’s sister and mother had settled in Canada and under family reunification rules they were able to find refuge and a new place to call home. In Canada, Schiff began her new life and worked as a medical technologist, specializing in hematology.

Schiff, the sole survivor of her entire family, had two sons, David and Michael, and now has six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. She surrounds herself with family, remembering what she has lost and cherishing what she has gained.

Following her retirement, she decided to commit to paper her memories in a book published in 1996 titled “Theresienstadt: The Town the Nazis Gave to the Jews.” This was followed by two other books in 2004 and 2005. Schiff also began speaking at schools as well as working with the centre to offer her personal testimony of the Holocaust, to educate young adults and to serve as a reminder of past atrocities.

Sitting in the library of her North York apartment complex, Schiff slams her fragile hands against an old wooden desk. “It must never repeat itself,” her voice strains after each syllable.

Her pearl bracelet and wedding band bang against the wood. “We must never allow a strong-armed bully, be it with an army or a stone, to attack a weaker man and to destroy people for no good reason.”

She pauses on each word, letting it linger in the air: “It. Can. Never. Happen. Again.”

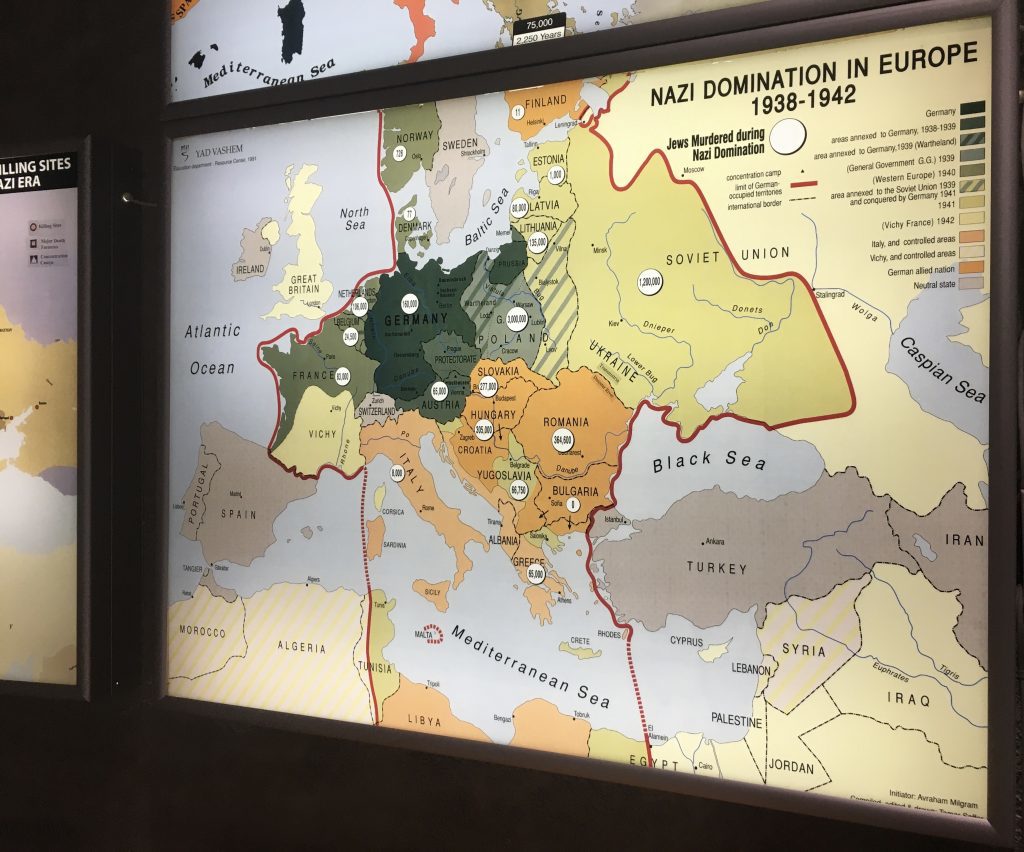

A visual representation of Nazi domination between 1938 to 1942. The red line represents the limits of German occupied territories and the small triangles represent concentration camps in these territories on Tuesday, Feb. 25, 2020. (William Dixon/T·)

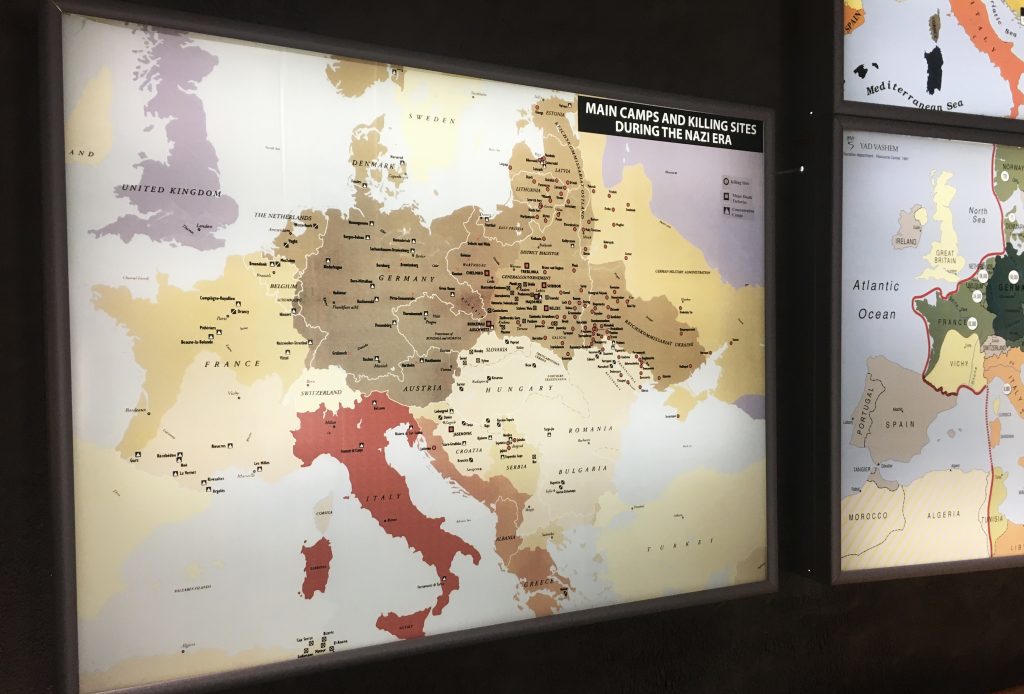

A graphic that illustrates the main concentration camps and killing cites during the Second World War. The red squares represent major death factories, the red circles represent killing sites and the black squares with a triangle inside represent concentration camps on Tuesday, Feb. 25, 2020. (William Dixon/T·)

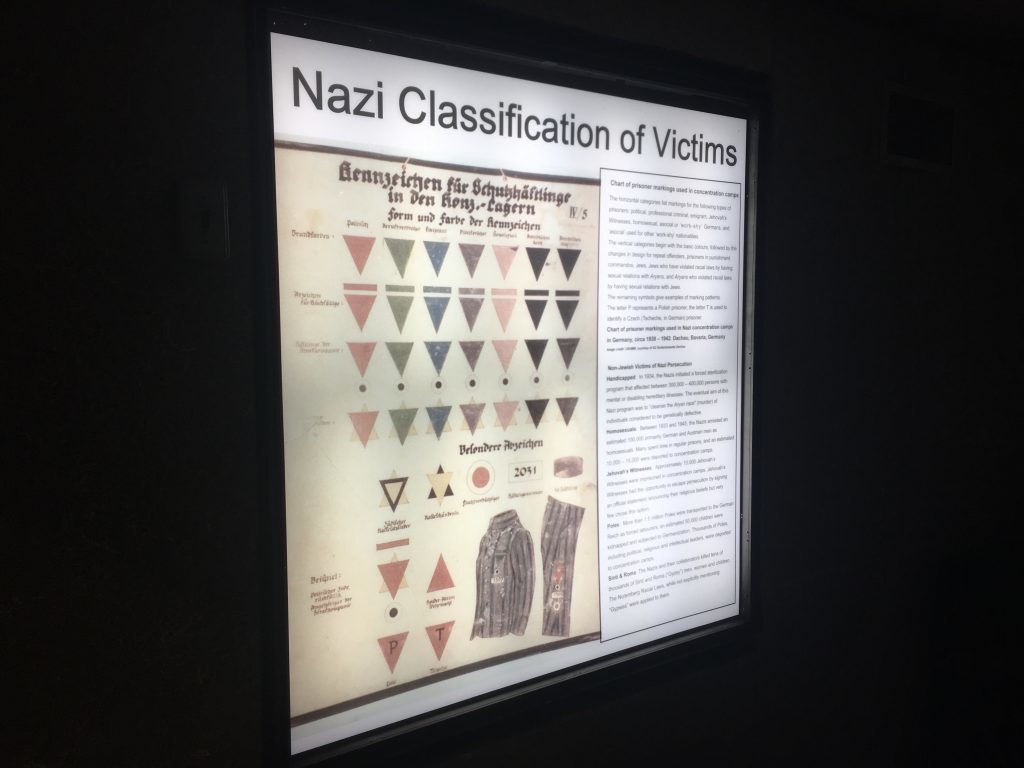

An infographic that identifies the Nazi classification system of their victims. The Nazi’s did not only discriminate against Jews but also blacks, homosexuals and other marginalized groups. There are also symbols to identify the intersectionality of the various victimized groups on Tuesday, Feb. 25, 2020. (William Dixon/T·)

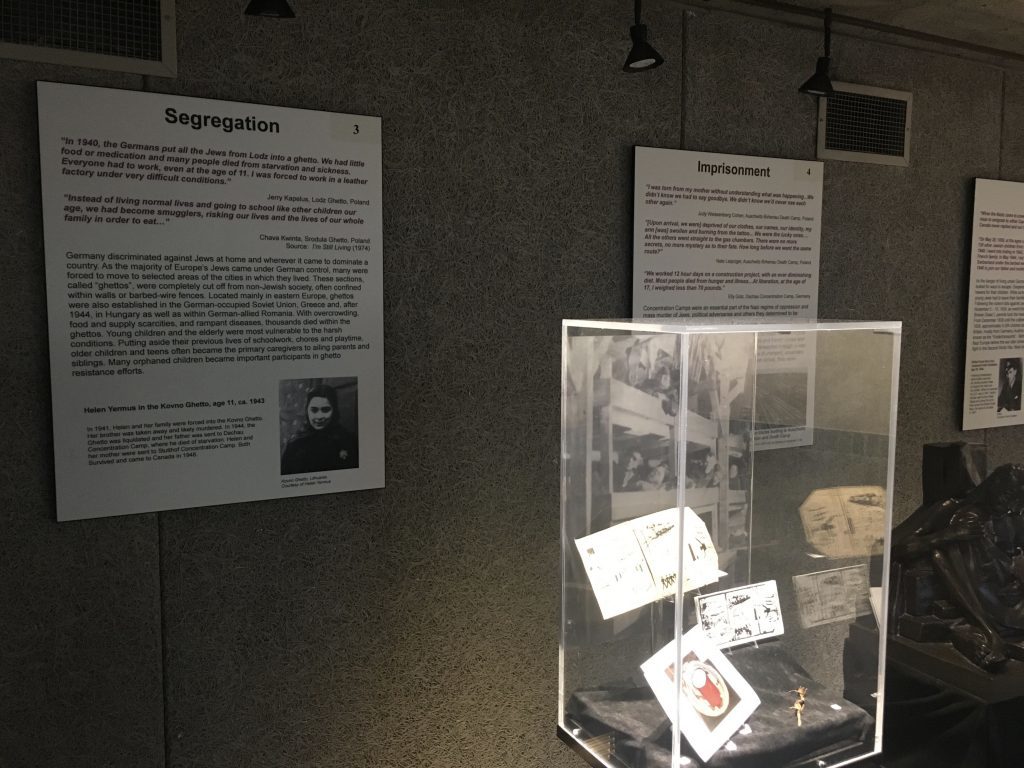

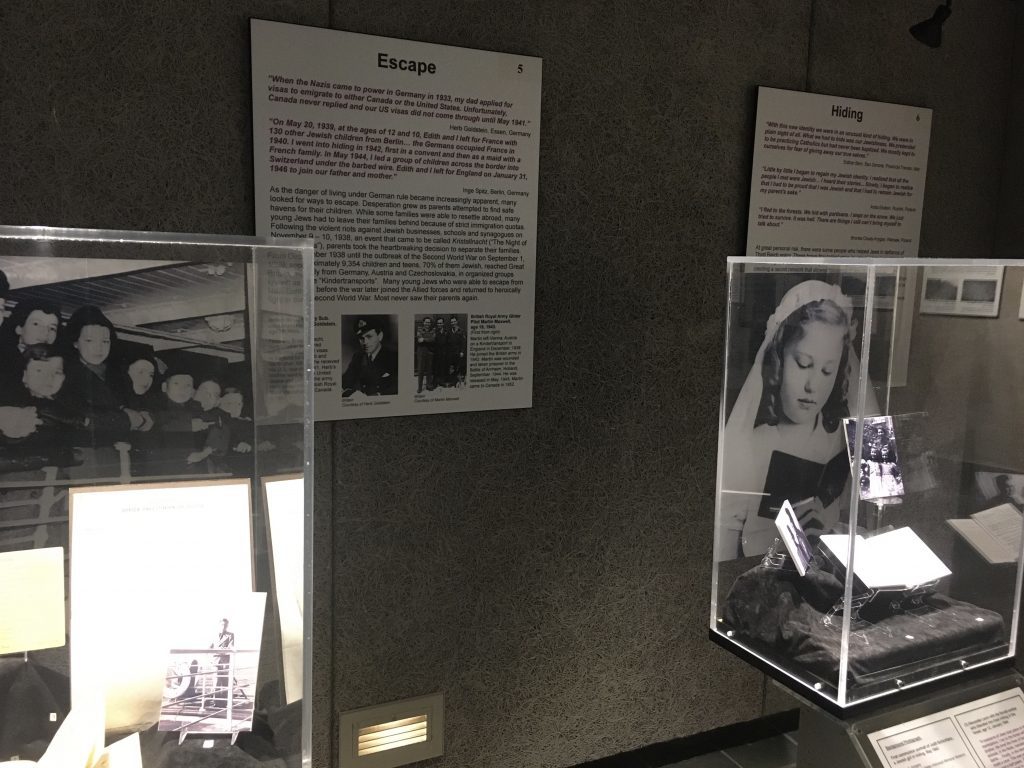

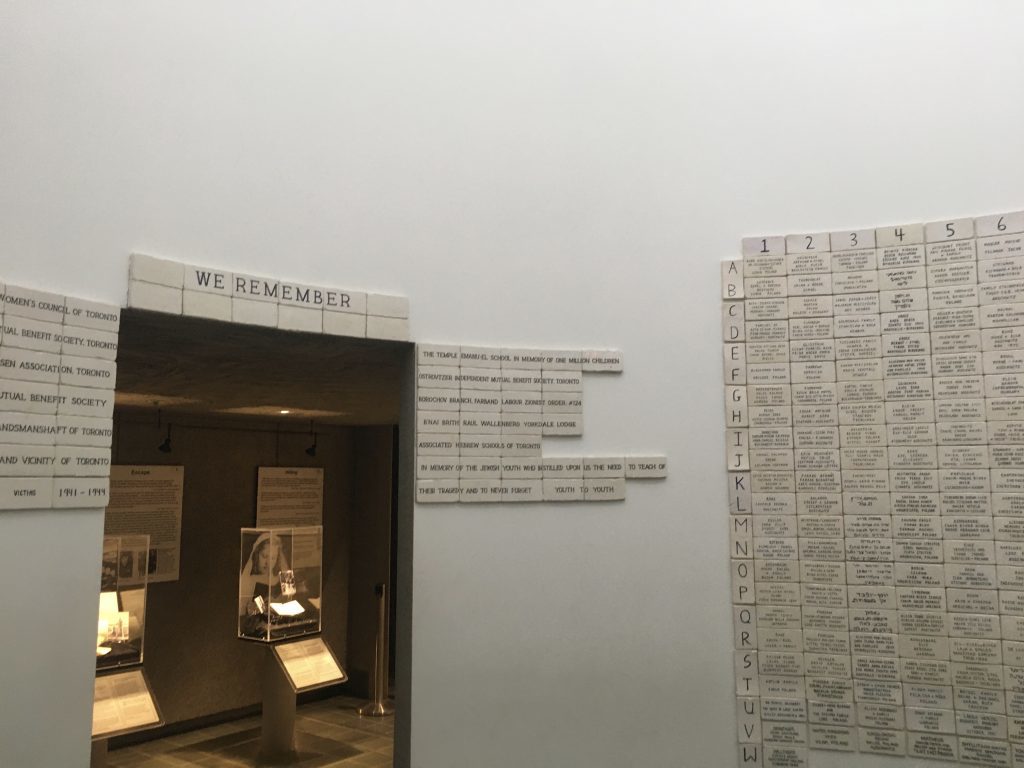

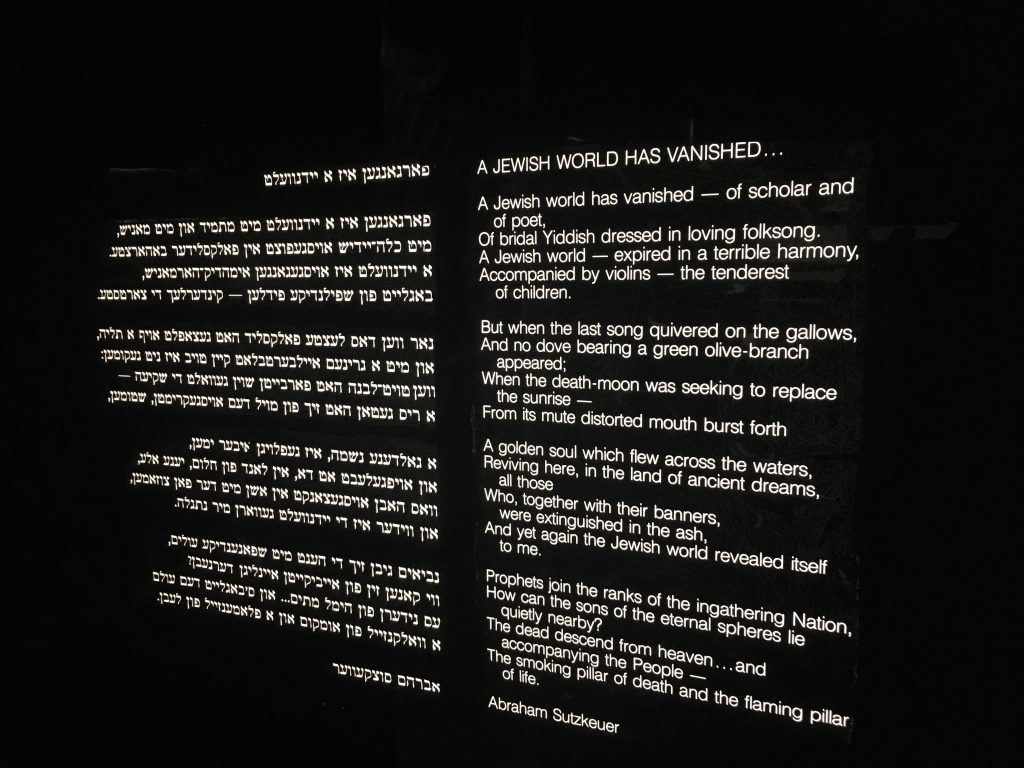

In the auditorium there is information about segregation, imprisonment, escape and hiding; all situations that many people faced during the Holocaust. The graphics are accompanied by artifacts from that complement the information on Tuesday, Feb. 25, 2020. (William Dixon/T·)

In the auditorium there is information about segregation, imprisonment, escape and hiding; all situations that many people faced during the Holocaust. The graphics are accompanied by artifacts from that complement the information on Tuesday, Feb. 25, 2020. (William Dixon/T•)

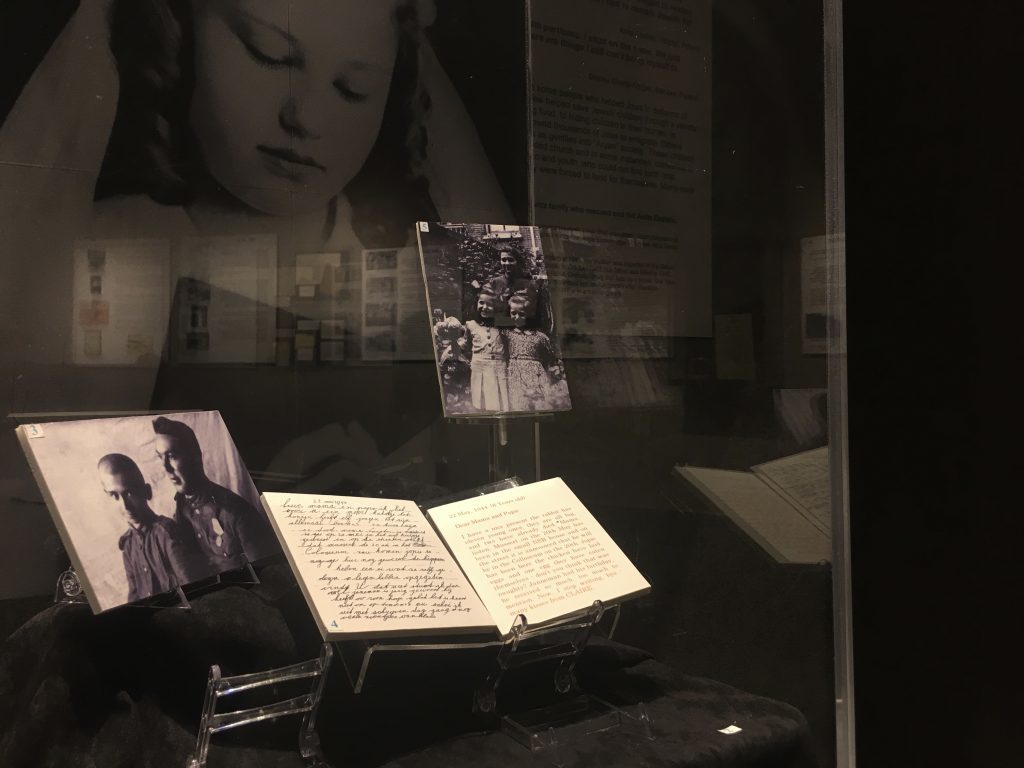

Within this glass box are three Holocaust artifacts: a photograph of Alexander Levin with the Soviet soldier who liberated him from hiding in the forest at the age of 12, a letter written by Clair Baum to her parents while in hiding in 1944 as well as a photograph of Clair Baum with her caregiver at the age of 8 on Tuesday, Feb. 25, 2020. (William Dixon/T·)

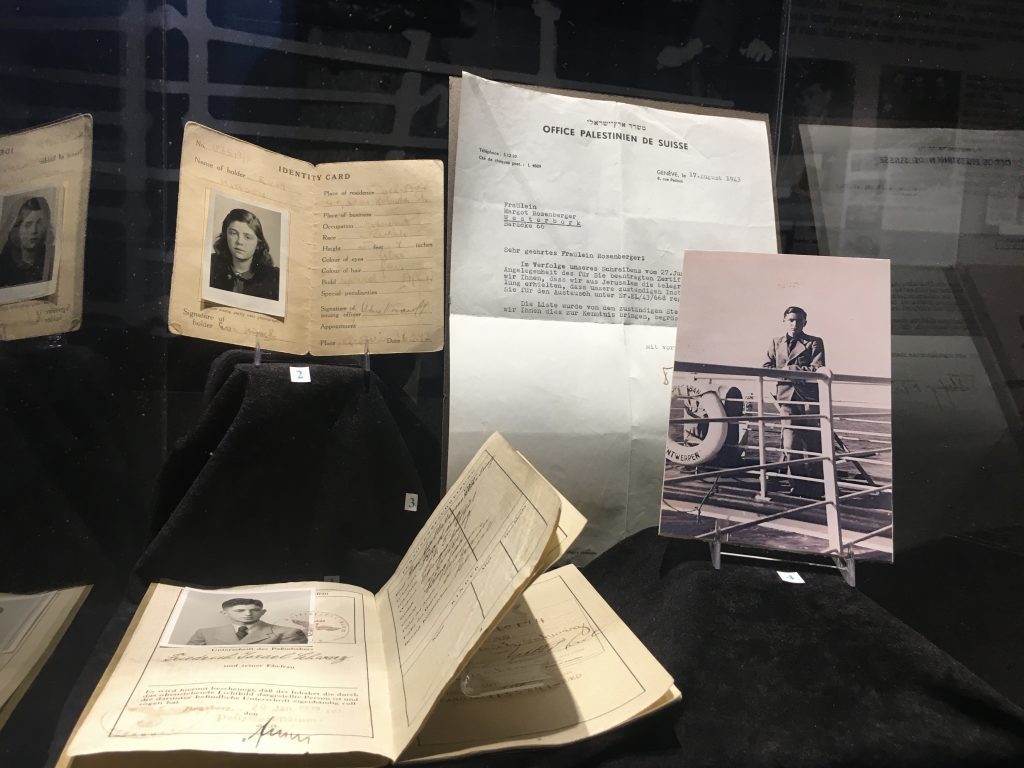

Another display of Holocaust artifacts donated by survivors that are connected to the centre. Within this display are 4 Holocaust artifacts: the German passport of Fredirich Schwarz, age 18, with a United States immigration visa issued Oct. 6, 1939, the identity card of Eva Hirsch, age 17, issued in 1942, a letter confirming Margo Rosenberger’s placement on the waiting list for entry in to Palestine in August 1942 and a photograph of a young Jewish refugee aboard a ship that sailed from Antwerp, Belgium to Rio De Janeiro, Brazil in the late 1930s on Tuesday, Feb. 25, 2020. (William Dixon/T·)

An inforgraphic about Theresienstadt and the courage of the youth. This graphic discusses the story of Vera Schiff and provides details on the concentration camp before, during and after the Holocaust on Tuesday, Feb. 25, 2020. (William Dixon/T·)

Vera Schiff, one of the centre’s most notable survivor speakers, answers questions from the Grade 10 students from MacLachlan College

after her presentation at the centre on Feb. 7, 2020. (William Dixon/T·)

A photo of Vera Schiff and her late husband, Arthur Schiff, who she met in the Theresienstadt. This picture was taken in 1945, Vera is 17 and Arthur is 39, when the couple finally arrived back in Prague, Czechoslovakia on Feb. 22, 2020. (William Dixon/T·)

Although the centre can get noisy due to the hustle and bustle of people going about their daily routines, behind the thick metal doors of the showroom there is nothing but silence.