By Olivia Burwell

The sun starts to set over a dozen tents, some blue and large, some green and small, and some adorned with rainbow flags. A young man, just a head taller than his green tent, walks across Alexandra Park with an empty Tim Hortons cup, ready to panhandle outside the nearby McDonald’s. Alexandra Park, located at the corner of Dundas and Bathurst streets , has become a hub for the homeless population of Toronto as tents overtake the park.

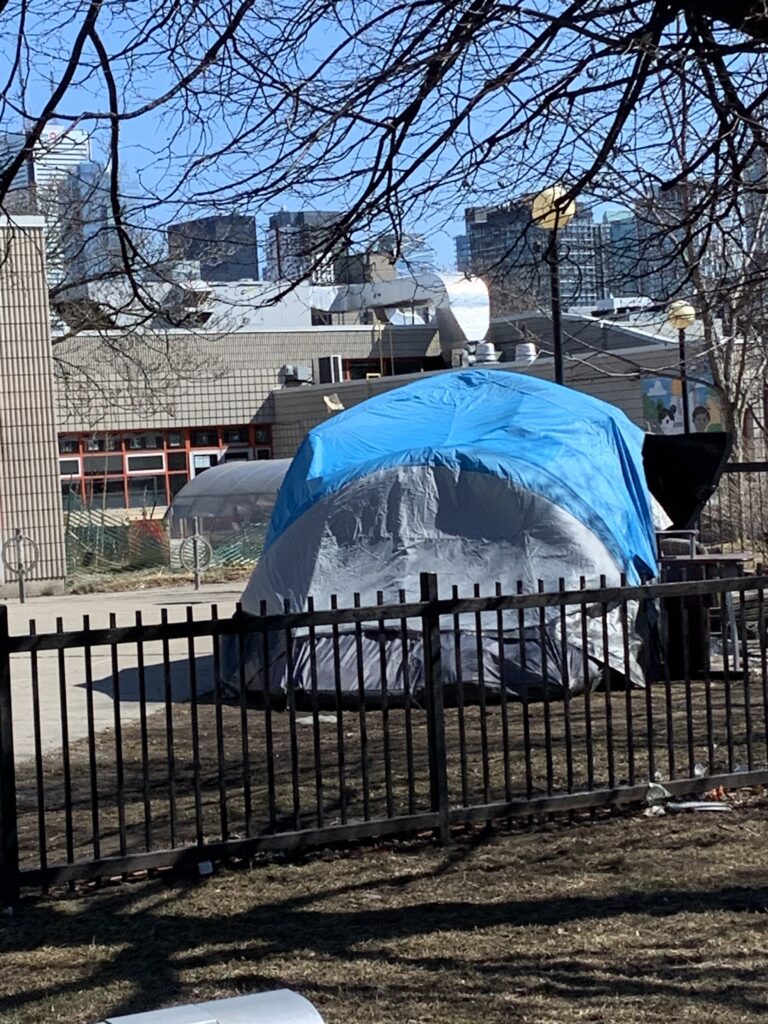

Mega tents outside the Sanderson Library March. 14, 2019. (Olivia Burwell/T.)

Tent In Alexandra Park March. 14, 2019. (Olivia Burwell/T.)

Tents within Alexandra Park March. 14, 2019. (Olivia Burwell/T.)

That population has a significant proportion of queer and trans youth, according to Dr.Alex Abramovich, an independent scientist at The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, who has been addressing the issue of homelessness among queer youth in his research for fifteen years.

“Queer and trans youth are being overrepresented among youth experiencing homelessness. Up to 40% of homeless youth identify as 2SLGBTQA+,” he said.

Evidence indicates that the number of trans, gender diverse, and queer people using Toronto’s shelter system appears to be increasing each year. The 2013 Street Needs Assessment’ survey performed by the City of Toronto showed that 21 per cent of youth interviewed identified as part of the queer and transgendered communities. In the same study conducted in 2018, that number had risen to 24 per cent.

This number is increasing and many services do not consider the intersectional needs of queer youth, said Abramovich.

“Many young adults and teens in the 2SLGBTQA+ do not feel safe in standard shelters. Transphobia and homophobia are still very prevalent in homeless shelters”, he said.

Through his research with CAMH, Abramovich proposed a possible solution called population-based housing, which is geared towards specific demographics, such as women’s shelter.

One such system, aimed at helping queer youth experiencing homelessness, is the YMCA Sprott House, which opened in January 2016. Located in a three-storey red brick house three doors up from a Shoppers Drug Mart on the corner of Bloor St. and Walmer Ave. in Toronto’s Annex neighborhood, Sprott House provides transitional shelter for up to 25 young people between the ages of 16 to 24.

The shelter’s director, Clare Nobbs, said that Sprott House is not just about finding youth a safe place to sleep. It’s about showing youth that there is a place that understands them, Nobbs said, noting that her staff are required to undergo LGBTQA+ sensitivity training.

“It’s about going beyond just shelter, it’s for them to have agency and a sense of well-being. They need to feel like they belong.’

Between donors and the government, Nobbs has to make a lot of people happy. Although her job is taxing, she discusses solutions to youth homelessness with a smile and passion in her voice.

Another organization that has shifted its focus to helping queer and transgendered youth on the streets is Youth Without Shelter. The organization does not have a housing program, but it has programs to aid with employment and staying in school.

Mike Burnett, the group’s community engagement specialist at YWS focused on community outreach said that the centre has always had an unwritten “zero-tolerance policy against discrimination,” but that the policy was codified a few years ago when youth asked for “it to physically be put on paper so that it was known that it was a very safe space.”

Early intervention and targeted programming are key in understanding and solving the 2SLGBTQA+ youth homeless crisis in Toronto. Current structures ignore the nuances of transgender and queer people in the shelter system, according to the Transforming the Emergency Homelessness System: Two Spirited, Trans, Nonbinary and Gender Diverse Safety in Shelters Project conducted by the Toronto Shelter Network.

“This is both on the individual level – seeing young people working towards and achieving their goals of financial independence and housing security; or on the broader level of affecting social policy that leads to increased awareness and therefore increased sustainable housing options for all,” Nobbs said.

During a presentation at Toronto’s City Hall to advocate for population-based housing, Abramovich said that the audience — deputy managers for city-wide operations — was moved to tears when he played a video of a young girl describing her experience on the street.

“The whole room suddenly became dead silent,” except for a muffled sob from one of the rows, Abramovich said. “A program like Sprott house is a life-saving program.”