By Shaki Sutharsan

Oscar Larsen was sitting in a plane thousands of feet above the Atlantic, flying to Canada from Sweden to start his master’s degree at McMaster, when he started to feel that something wasn’t quite right. The feeling only grew as he stepped off the plane and boarded a bus to Hamilton, but perhaps it was just the exhaustion talking after being awake for nearly 24 hours. When he finally arrived in the neighbourhood where many McMaster students lived, he was on the last dregs of his energy.

He walked up to the front door of the nondescript bungalow he was meant to be renting a room in, knocked on the door and waited, shivering in the early February chill.

“I didn’t have a better plan or a backup plan, or anything. I was just hoping that she was an honest person,” Larsen recalled.

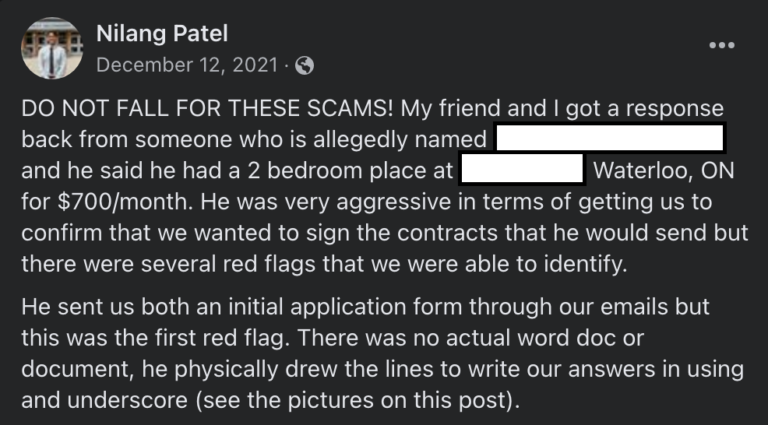

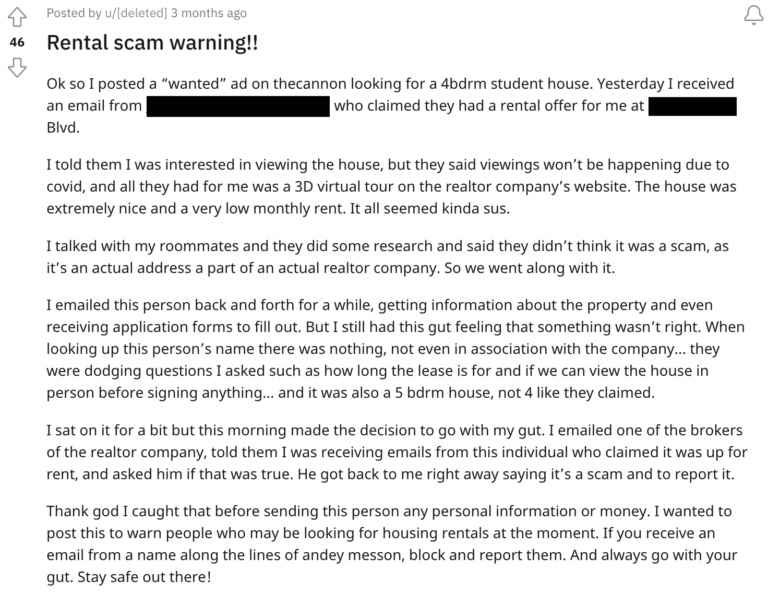

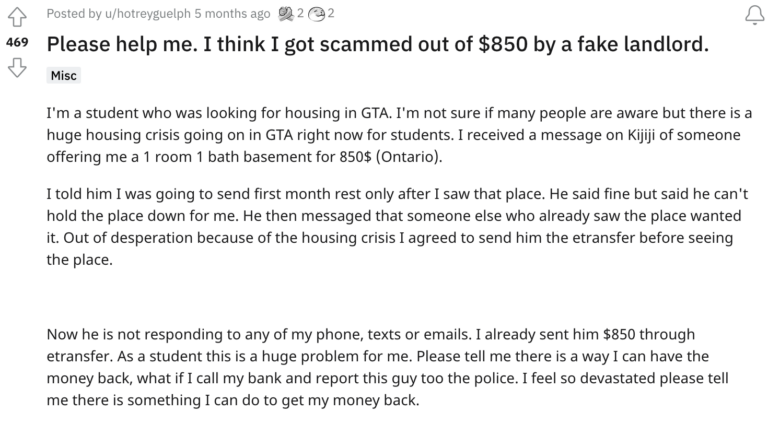

Larsen’s experience isn’t as uncommon as you might like to think. The Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre reported 610 rental listing scam complaints in 2020, an increase from previous years because pandemic restrictions meant that hopeful renters couldn’t visit a listing in person, making it easier for scammers to pass off listings as their own. Between January and July of the same year, Waterloo Regional Police reported that out of 41 rental fraud complaints it received, 32 victims lost about $60,000. And while fake landlords can face up to two years in prison for fraud, they are often able to get away with it by hiding their real identities behind throwaway Facebook profiles.

Students, in general, are often easy targets for rental scammers, according to Toronto-based realtor Curtis Yim. “Students don’t really know what to look for,” he said, “especially international students as they’re not here.” Knowing that international students or students living out of the province can’t see the place before signing any agreement or sending a deposit, scammers use that to their advantage, Lim said.

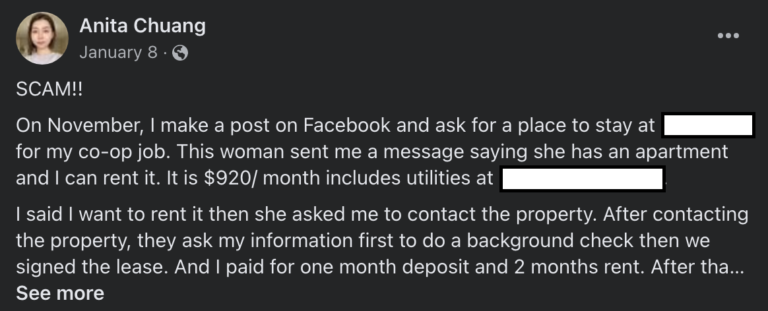

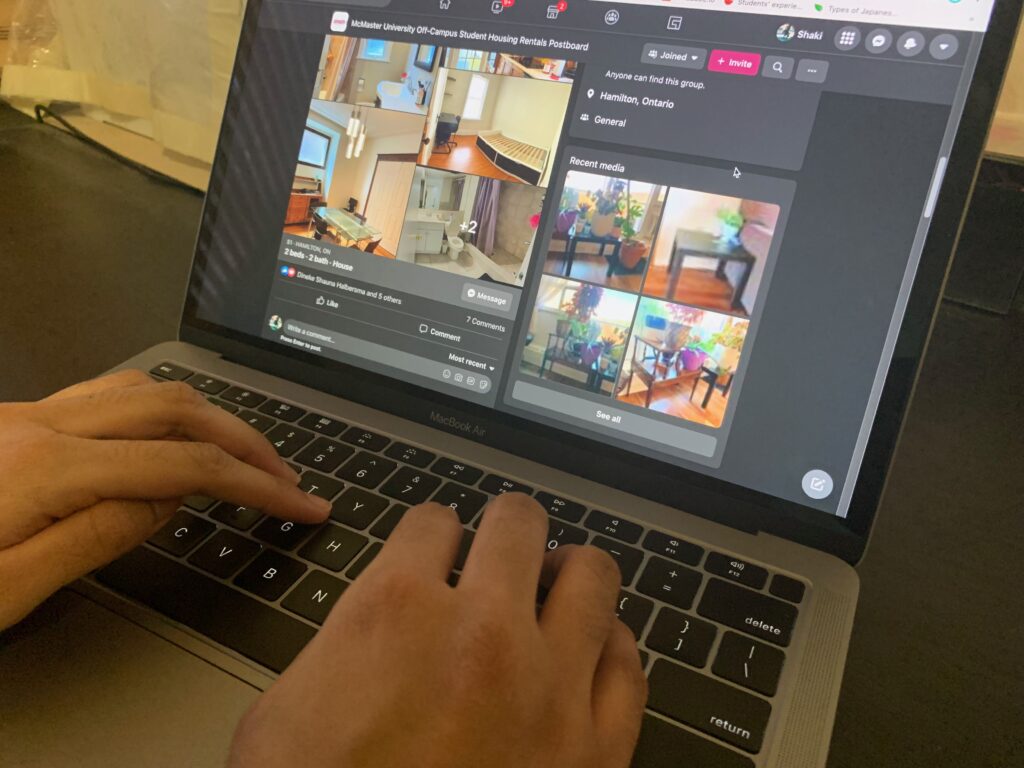

Student-run Facebook groups like McMaster University Off-Campus Student Housing Rentals Postboard and Student Housing Waterloo are constantly updated with new posts advertising listings for private rentals. Many of these groups are public, meaning anyone can post in them: potential landlords, students subletting their rooms for the summer – and scammers looking to make a couple thousand dollars off a desperate student. A quick search in any of these groups will bring up posts from students warning others of potential scammers or recounting their own experiences being scammed after responding to a listing.

Toronto-based realtor Kam Mirza said in an interview that most scammers will find a random listing online and post it in a Facebook group, lure someone into connecting with them, and then “ghost” the victim once they’ve received the money.

That’s what happened to Kelly Hemstock-Weeks, a student at Mohawk College: she had signed a lease and paid $1,600, first and last month’s rent, to a landlord who had posted the listing for the apartment on Facebook. But when she tried to access the message thread with the landlord, “Lo and behold, she’s deleted everything, she’s blocked me, unfriended me,” Hemstock-Weeks said. She immediately went to the police, who told her there wasn’t much they could do since she’d already sent the money.

To prevent falling victim to a rental scam, Yim advised always seeing a listing in real-time, either in-person or via video call, before sending over any money or signing a lease agreement.

Although it was too late for Larsen, he managed to get through his ordeal with the kindness of the woman who’d answered the door. She invited him inside once she realized he’d been the victim of a scam. She and her housemates then contacted McMaster faculty and campus security, and helped Larsen report the incident to Hamilton police, who told him it was unlikely that anything could be done. Larsen ended up staying in a temporary residence on campus until he found a place of his own nearby a couple of weeks later. He didn’t get his money back, nor did he hear back from police.

In hindsight, Larsen regretted that he’d been in a rush to find a place in time to begin his master’s. “That left very little time to do research…what to be careful about, what to look out for,” he said. “I didn’t really know what to expect.”

For additional advice, check out University of Toronto’s tips for protecting yourself against housing scams and the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre’s rundown of how you can report a scam.