By Julia Lawrence

Queer journalists have learned that if you’re working for a traditional mainstream media publication, you better have a thick skin because you won’t always fit the mould.

If you want to have a social media presence online, you better have a thick skin to deal with the hate and abuse you’re bound to receive. If you want to oversee editors and team members, you better have a thick skin because many will question your decisions or biases for no reason other than your LGBTQ connection.

Today, one way journalists manage to avoid discrimination is by setting up their projects outside traditional media entirely. Like podcaster and former co-host of CBC’s “Inappropriate Questions,” Elena Hudgins Lyle. They started the podcast while studying media production at Ryerson University.

The show helped listeners learn more about themselves and those around them. Lyle says most listeners were mainly older folks who wanted to understand terms better for their children.

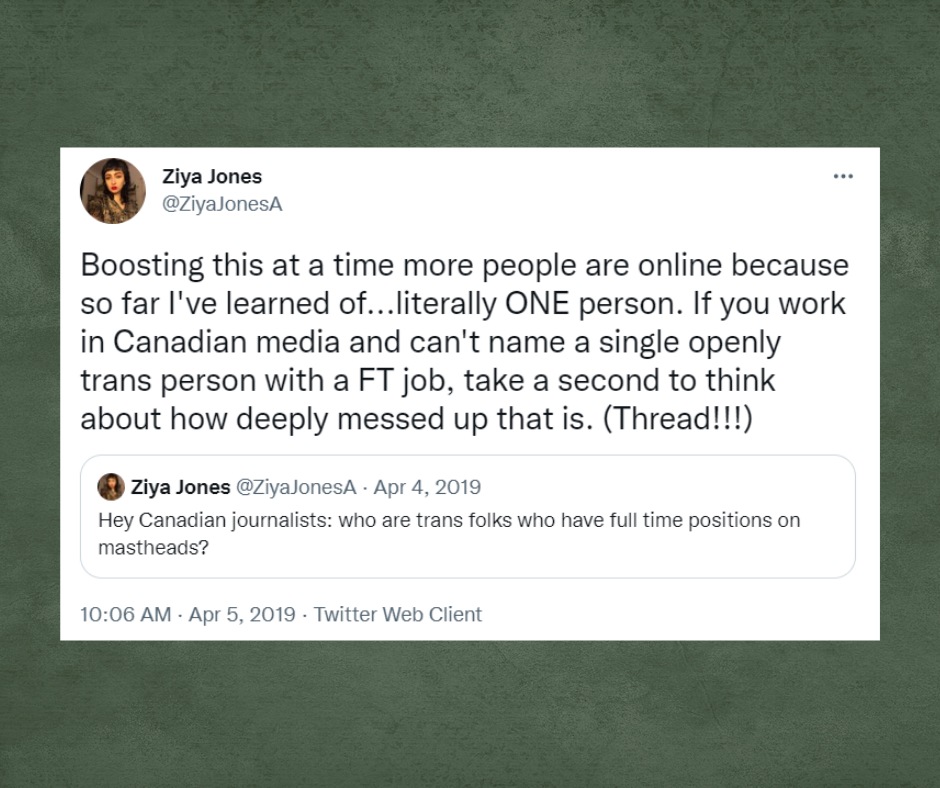

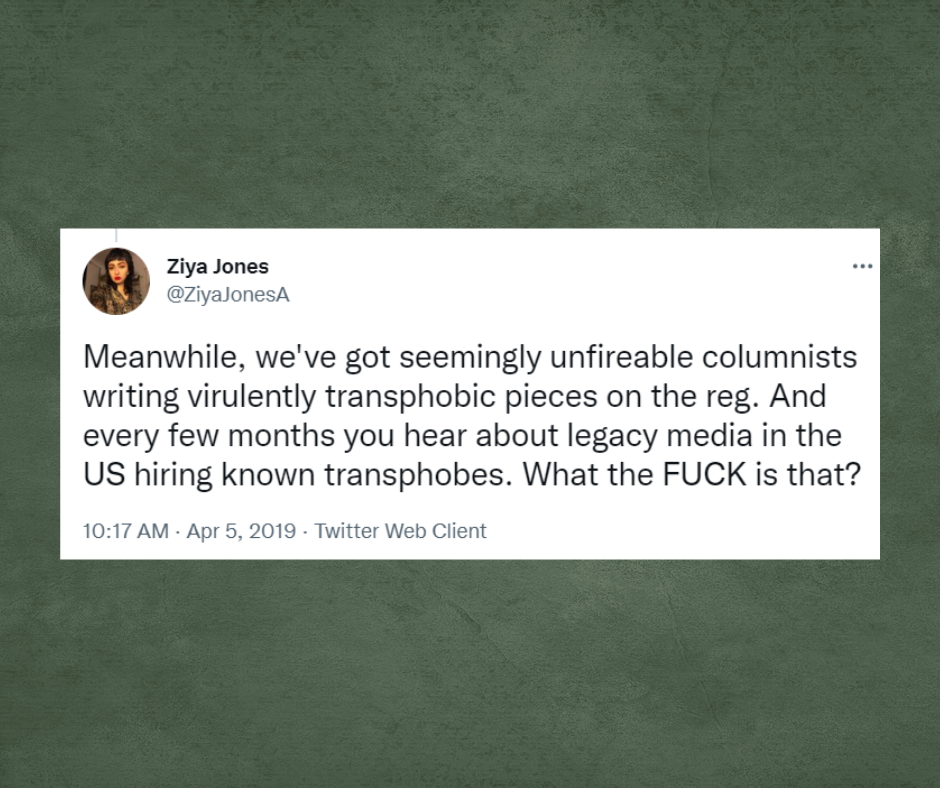

“You get (users) who are transphobic all the time. Any time you write or say anything about trans people online, there is going to be somebody that finds it and comes for you. It is a hazard of being a trans or non-binary person in media right now.”

People seem to feel they should be able to comment on your writing and you as a person, Jones says.

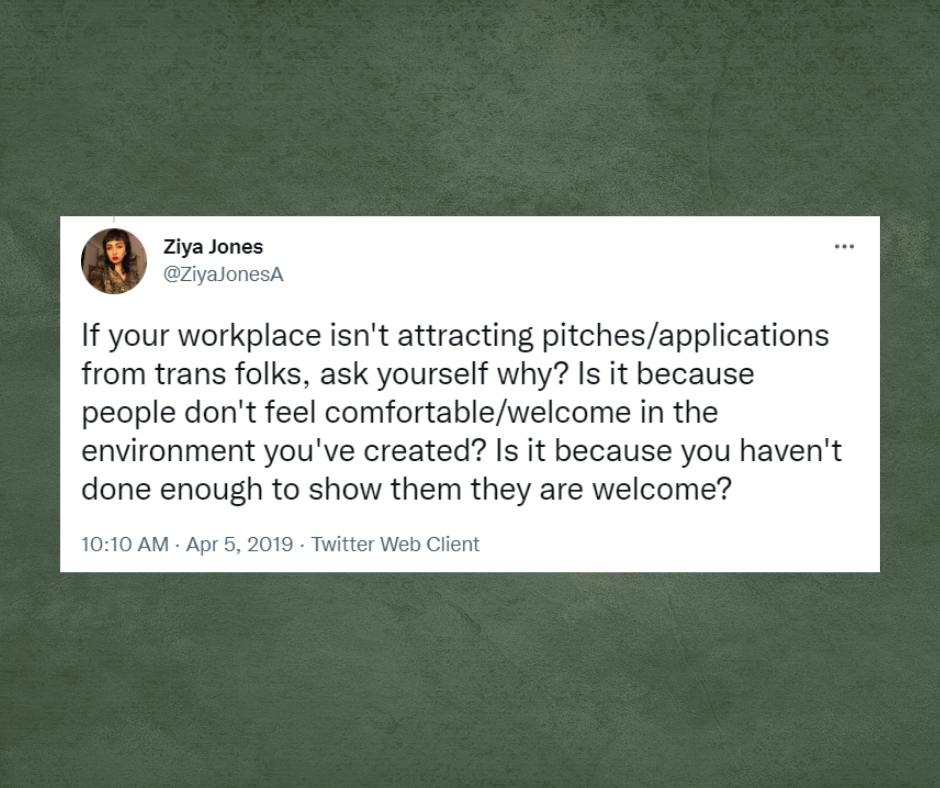

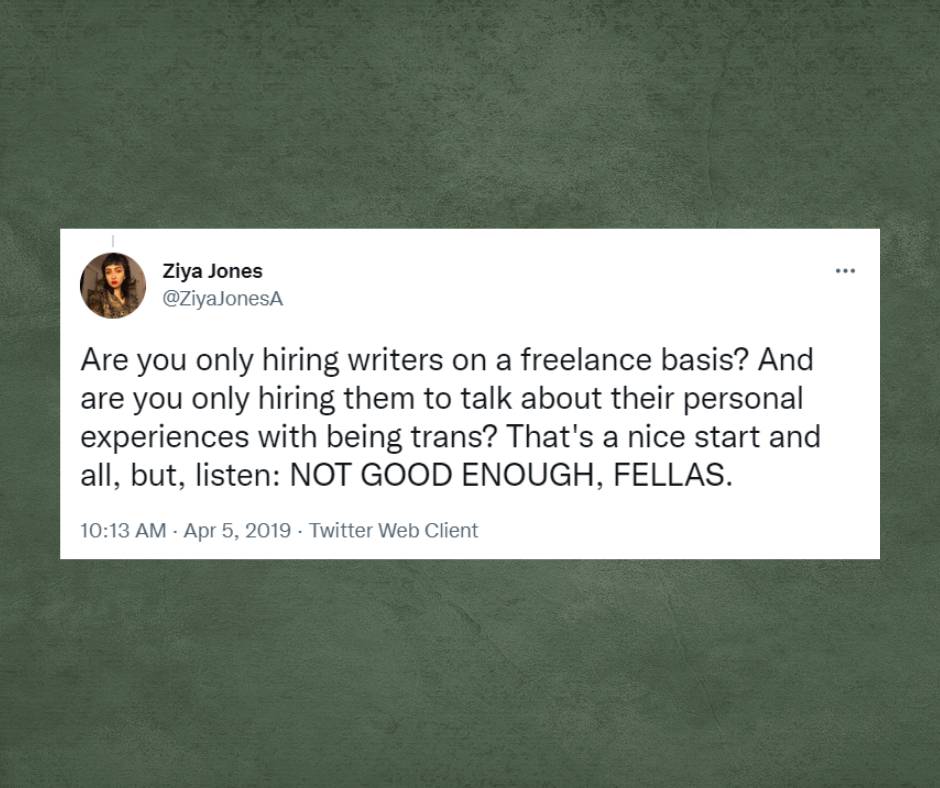

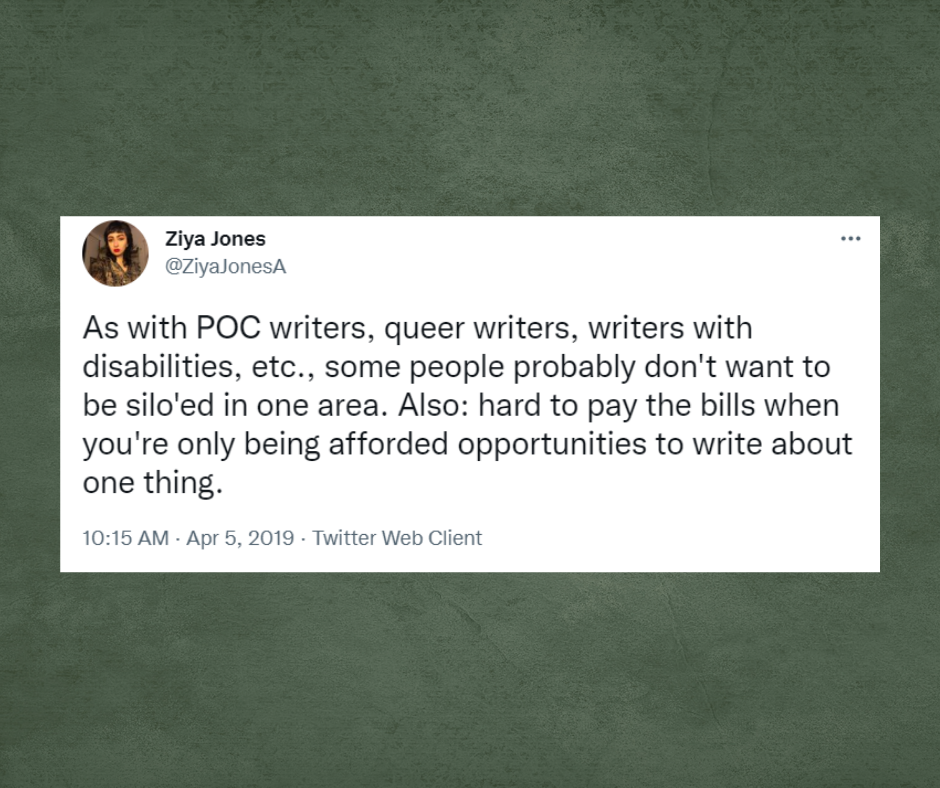

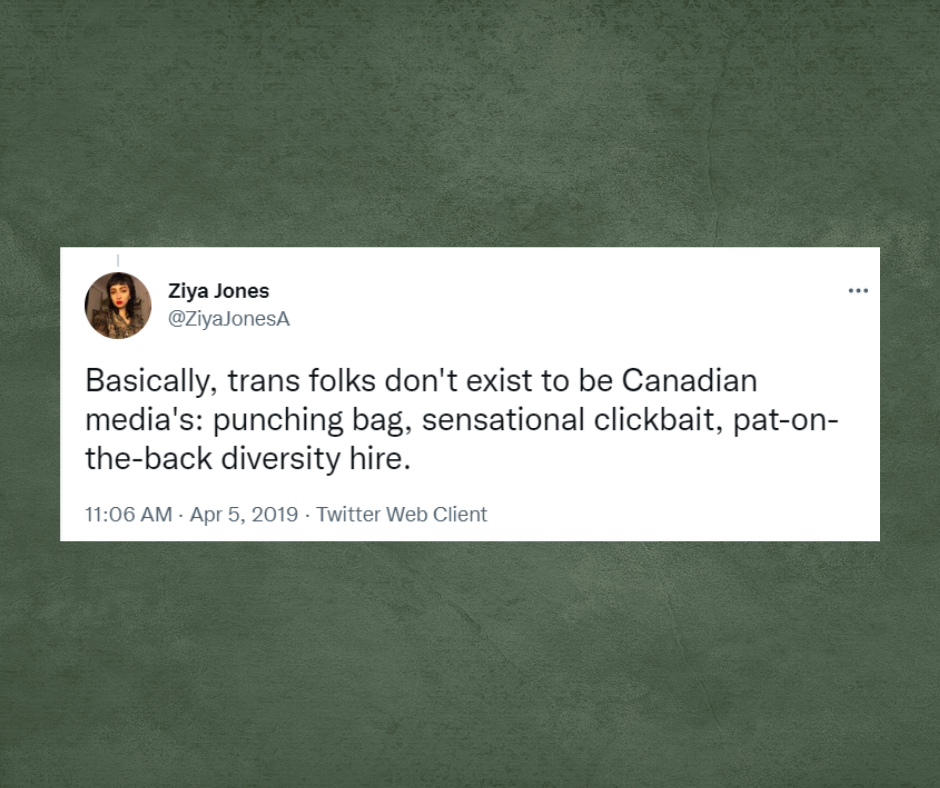

For many queer journalists working in newsrooms today, the consistent misgendering of trans and non-binary writers, pigeonholing the only LGBTQ journalists and a noticeable lack of diverse representation are some of the realities that affect their physical and mental well-being.

Lack of diversity, understanding and acceptance of the LGBTQ community is an age-old problem in the industry.

Nearly 20 years ago, in The Peterborough Examiner newsroom, Andrea Houston and her editor got into a heated discussion over the coverage of the Peterborough Pride parade. Houston’s editor wanted to rewrite the lede of the story to have a more conservative angle and pushed it to be about how the parade was a nuisance blocking traffic in front of downtown churches on a Sunday in the city.She knew her editor was wrong to suggest adding conflict in the story that took the focus away from the event. Houston used her role as a reporter and advocated behind the scenes to refocus the story on the event itself and the impact it had on the LGBTQ people that attended.

“I recognized that putting the focus on a few disgruntled church-goers rather than the hundreds of young people marching for LGBTQ rights is, not only unfair journalistically, but an insult to the entire history of the Pride movement.”

A national study in 2015 by the Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion about discrimination against LGBTQ media employees surveyed 1,410 workers. It found that people who identified as LGBTQ were 50 per cent more likely to say they witnessed discrimination in the workplace (33.2 per cent) than non-LGBTQ people (21.1 per cent). Those who did not identify as LGBTQ were almost twice as likely to report that there was no discrimination in their workplace – 67.2 per cent to 38.3 per cent.

Lyle says there was no discrimination within their production team at CBC, as members were mainly a part of the LGBTQ community or friends with the cast. The team created an open work environment that didn’t need to have workshops on how to avoid biases or transphobia, as most of the people in the workplace were part of the queer community and understood right from wrong.

“The team members and I were very much queer, so what may apply to other outlets didn’t apply to ours. We tried to bring on people who can relate to our show or showcase people during episodes on topics unrelated to their identity, to keep things balanced between showing people from our community and respecting that they have other interests to talk about.”

The first place the industry can start to become more accepting of the LGBTQ community is to learn about it. Multidisciplinary producer and diversity workshop organizer Dev Ramsawakh has a simple test to tell if a publication wants to make a change in its newsroom because it’s the right thing to do or because it feels pressured to do so by staff or higher-ups. The company will have Ramsawakh come in more than once, provide its updated policies for feedback and encourage staff to ask Ramsawakh more questions or explain the workplace material again.

Learning about the community also sets up habits for the future, like getting rid of misgendering someone just because you don’t understand what it means or looking at a person as more than just their label.

Several queer journalists suggested including a source who identifies with the LGBTQ community in stories that have nothing to do with the community per se. They are experiencing physical and mental effects because of COVID-19 as much as anyone else, and they have opinions on Toronto’s housing market. They have views on a variety of issues, just like everyone else.

Recognizing the importance of these changes – and following through – is a crucial area in which the media industry can do better.

Ramsawakh says, “We are navigating an entirely new landscape right now and creating it as we go because the old landscape wasn’t doing it for us.”

“There’s a lot of history we can learn and grow from, and we are at a big turning point in terms of what work we create right now.”