By Abbie North

On a summer’s day in June 2019 with just one month left to complete a two-year fashion diploma at Toronto Film School, Aman Gill found themselves lying in excruciating pain in their university classroom, on a makeshift bed of several chairs that fellow students had quickly assembled.

Gill’s herniated disc, the result of a car crash five months prior, was not only physically agonizing, but it was also draining their mental and emotional health to a breaking point. They decided to leave the program, losing the thousands of dollars they had already invested in their studies and incurring an additional $10,000 fine for dropping out a month early.

“I dropped out because they told me that I couldn’t take a week off,” Gill said, “Why am I doing this to myself? Why am I going to a place that won’t let me rest? They fined me, and I was like ‘Whatever.’”

Financially, physically and emotionally exhausted and in need of a job, Gill turned the few mental reserves they had left to launch a clothing brand.

But Gill needed money, and as someone with no generational wealth and carrying debt from a divorce, Gill faced multiple barriers and was rejected from at least 10 funding applications.

Gill’s experience of getting sidelined when looking for funding resources is one that is shared by other queer entrepreneurs of colour who face societal hurdles, stereotyping and discrimination.

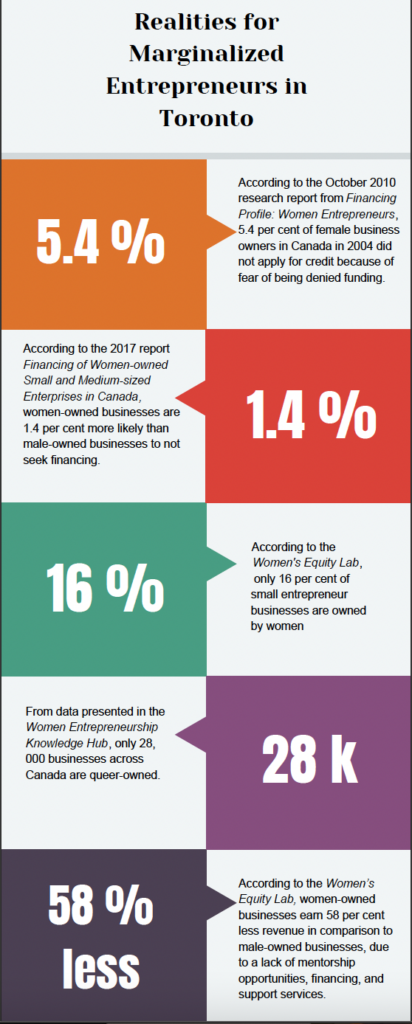

Women and marginalized entrepreneurs often fund their businesses using their own money, and according to a 2010 Government of Canada report on small- and medium-sized enterprises, about 5.4 per cent of female business owners in 2004 did not apply for credit because of fear of being denied financing.

More recent statistics from the government’s 2017 report Financing of Women-owned Small and Medium-sized Enterprises in Canada, shows that women-owned businesses are 1.4 per cent more likely than male-owned businesses to not seek financing because they expect their requests to be turned down.

Wendy Cukier, founder and leader of the Women Entrepreneurship Knowledge Hub, an online resource, said that women and marginalized entrepreneurs tend to have smaller businesses, less financing, fewer reserves and fewer physical assets. These factors can lead to stereotyping and discrimination by banks and government agencies.

“[Women] are in a system based on industries that are male-dominated, and women are what we call discouraged borrowers. They feel like they don’t have a grasp of financing, they think they are going to be turned down and they tend not to apply for funding as often as men,” Cukier said.

Gill is now the Creative Director of AADHE Clothing, a Toronto-based business focused on creating a safe space for marginalized entrepreneurs. Located in their home just outside downtown Toronto, Gill’s blue-walled office displays pictures and artwork flanked by thrifted and repaired pencil holders on their desk, along with their daughter’s first drawing framed in gold.

As a dual-cultured Punjabi and Torontonian, and queer business owner, Gill is aware of the barriers that come with being from a marginalized group.

“After my divorce, I was left with almost $100,000 in debt, and I decided to do something called a consumer report to lower my overall debt, but it comes with a low credit score for the term of the contract. My contract is up in 2025, and it has lowered my debt to $20,000. This means a majority of my funding has come from my own pocket,” they said.

Gill said entrepreneurship is a business field dominated by men, and that funding opportunities exist in a world built for men by men. The numbers support Gill’s statements.

According to the Government of Canada’s Women’s Equity Lab, a group of more than 150 women investors, about 16 per cent of small businesses are owned by women. And according to the WEKH’s State of Women’s Entrepreneurship Report from 2022, only 28,000 businesses across Canada are queer-owned.

The WEKH 2022 report outlines five factors that funding agencies use to make financing decisions – capacity, collateral, capital, character, and conditions – that are based, to a large extent, on historical patterns that disadvantage women and others.

Addressing the character portion of the ‘five C’s,’ Gill’s mentor who is also queer advises them to identify as a woman when applying for grants and loans, because experience has shown them that the more marginalized identities one adds up, whether that be race, religion, gender, or sexual identity, the harder it becomes to access financing.

This advice is a shift from the things Gill learned from other heteronormative, straight mentors, when they felt there wasn’t an element of themselves that was understood.

“Women and non-binary grants are rare. Even just non-binary grants you never see,” Gill said.

According to the Women’s Equity Lab, women-owned businesses earn 58 per cent less revenue in comparison to male-owned businesses, due to a lack of mentorship opportunities, financing, and support services because of underlying gender inequalities in business.

Gill said they wouldn’t have had a lack of revenue or made the mistakes they did with their business if they had had access to the correct funding.

Building off of rejections, numerous grant applications, and conversations with loan officers and banks, Gill said that proper access and opportunities to fund a business are essential to succeeding as an entrepreneur.

Cukier said the easiest thing to do instead of creating more programs with ‘women’ or any other marginalized identifier in the title, is to analyze existing programs to see if there are biases built into funding programs that exclude women.

“The most powerful tool to unlock access to way more support and resources is to look at where you are spending your money and ask the question why is it that only 10 per cent of grants are going to women,” Cukier said.

To provide other women and queer individuals with a chance to succeed as entrepreneurs in Toronto, Gill has set a goal to dispense their own grants and resources to the community.

“Hopefully in the future, I can become a place where non-binary folks can say, ‘Okay that’s my safe space’ where [they] have all the education [they] need and all the links for where to go,” they said.

Surrounded by pieces of clothing with bursts of color, embroidery, different neck shapes, arm lengths, pant lengths, skirts, and a lot of mixing and matching, Gill writes a hopeful list of improvements if given proper funding and resources: $10,000 per month on digital marketing, a living wage for the interns, two seamstresses, a pattern maker, a social media content creator, a copywriter, a sales strategist, two market vendors, and two screen printers. And finally, enough money to pay themselves.

Gill knows this list is unrealistic until adequate funding is made more accessible for marginalized entrepreneurs.