By Samreen Maqsood

Steve Teekens trudges through the trails of Hillcrest Park with a few other Indigenous men from the Indigenous emergency shelter, Na-Me-Res. The sky is a clear blue, fluffy white clouds shaped like cotton candy floating by. The air is light and crisp, the indication of spring coming early with the bright green buds on the old brown trees. A group of red-winged blackbirds are circling the trees,chirping brightly. It’s a perfect day for gardening and growth, he thought to himself.He reaches a little garden area not far from the kids’ playground. There, the medicinal plants and herbs are growing in the healing garden he started a few months after COVID-19 became a global pandemic. The garden is called Medicine Wheel Garden.

Teekens is the director of Na-Me-Ras (Native Men’s Residence), an Indigenous emergency shelter that provides programs, services and transitional housing for homeless Indigenous men in Toronto. After joining the shelter in 1995, he worked to develop a structure that would help take homeless Indigenous men off the streets and into a safe support system. This soon turned into Na-Me-Res offering affordable housing under Teekens’ direction.

The shelter has two locations. The temporary shelter called The Men’s Residence is located at 14 Vaughan Rd., and is open to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous men. There, the residents receive access to cultural programming and assistance in finding permanent housing.

The second location called Sagatay (A New Beginning) is located at 26 Vaughan Rd. This transitional housing system is for those men who feel as if they are ready to make the move from homelessness to permanent housing. It offers access to cultural programming and skills development.

In the Medicine Wheel Garden, Teekens teaches the men who are staying at the shelter (Na-Ma-Res calls them residents) how to grow traditional and medicinal plants and herbs. In the fall season, they harvest these medicinal plants and learn how to make plant medicines, given the qualities of the plant and nutritional knowledge around them.

During this spring season, the residents are in the greenhouse, germinating the seeds and getting them ready to plant. They grow and harvest sweetgrass for ceremonial smudging, squash, corn and beans, which are considered historical vegetables of local tribes and cedar for teas and medicines. As the weather starts to get warmer, Teekens and the residents head down to Hillcrest Park and start planting.

“To the average eye, the plants may look like weeds to them. But these are Indigenous plants to this region of Ontario and they’re not imported,” Teekens said.

“You learn what our ancestors used them for and how they were used. There’s something healing about working with the earth, mixing your hands with the dirt and working with Mother Earth. There’s some sort of connection there.”

Steve Teekens, director of Na-Me-Res

The healing garden is just one of the many activities and workshops Teekens organizes at the shelter. The men learn healthy living, public speaking and confidence skills, so that once they feel ready to leave the shelter and find a job, they are prepared.

Vulnerable communities such as the Indigenous population that do not have access to proper resources to overcome difficult situations, such as a global pandemic, are more prone to death and illnesses. According to Indigenous Services Canada, 1,736 COVID-19 cases were confirmed in First Nations communities in Ontario between July 2020 and April 2021.

According to a Canadian Physiotherapy Association report in December 2020, Indigenous communities around Canada are experiencing high rates of underlying health conditions that can lead them to severe illnesses from COVID-19. A lack of access to clean water, populations facing homelessness and people living in poverty are some of the reasons why Indigenous people suffer disproportionately from COVID-19.

Teekens remembers the death of Brian Sinclair, the Indigenous Canadian who was left to die in 2008 in a Manitoba hospital. The medical staff assumed he was “drunk” and “sleeping it off,” which is why the judge in his case labelled his death as “preventable.” Teekens says many ill Indigenous people who don’t drink or use drugs are assumed to be drunk or high when they seek medical help.

“Racism kills. There’s a number of studies that demonstrate that we know ‘by Indigenous for Indigenous’ is the more culturally safe way to go when it comes to delivering medical care,” said Teekens.

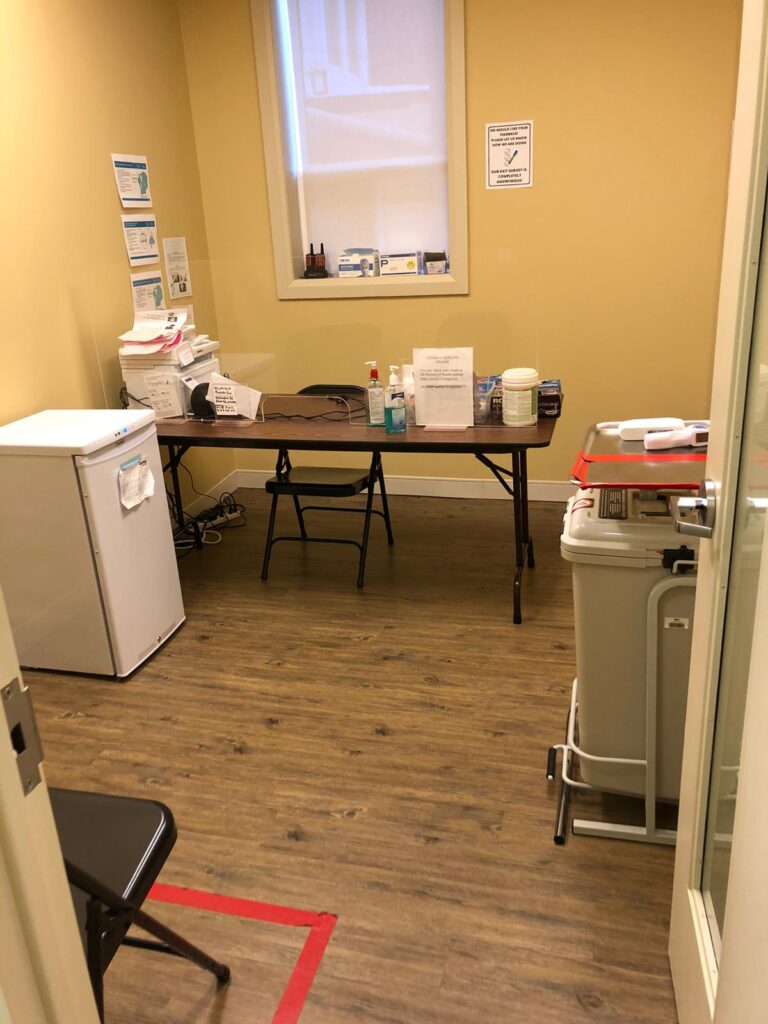

That is why he worked with Dr. Janet Smylie, a Métis physician and Canada research chair in Indigenous Health based at St. Michael’s Hospital, to open up a Indigenous-led shelter for COVID-19 testing and vaccinations. The centre, called Auduzhe Mino Nesewinong (Place of Healthy Breathing), opened in October and offers COVID-19 testing, contact tracing and outreach supports. It operates four days a week, each on four-hour blocks.

As of the end of March, only 72 Indigenous people have been vaccinated from the centre since it opened. As of March, Smylie estimates there are about 60,000 Indigenous people in Toronto eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine.

“By Indigenous for Indigenous is the more culturally safe way to go when it comes to delivering medical care.”

Steve Teekens, director of Na-Me-Res

While a testing and vaccination centre are helpful, it does little to keep up people’s spirit, according to Teekens. COVID-19 has taken not only a physical toll on people, but also a mental and emotional toll. A survey by Statistics Canada shows that 60 per cent of Candian Indigenous people say their mental health is worse due to COVID-19.

“Seeing the plants transform throughout the process is sort of like the men healing from their own traumas and progressing to a brighter future.”

Steve Teekens, director of Na-Me-Res

That is why during these difficult times, many communities such as Na-Me-Res and Ryerson University, have looked to healing gardens to offer peace, self-care and tranquility.

Healing gardens have long been an important part of Indigenous cultures, often deemed as a source of improving mental, physical and spiritual health. Teekens said the healing gardens are essential in providing spiritual comfort and offer connection by using outdoor spaces for faithful practices, such as prayers, meditation or ceremonies. Teekens says it helps the men to connect back to their culture as they learn the medicinal qualities of the plants they are growing.

“You don’t need a double blind, randomized controlled trial to know that you feel calm in nature.”

Michael Mihalicz, Indigenous advisor for Ryerson’s Ted Rogers School of Management

Seeing the plants flourish and develop, pulling out the weeds and seeing the plants grow to be strong and healthy, Teekens says just by being a part of the process, the men heal.

“Seeing the plants transform throughout the process is sort of like the men healing from their own traumas and progressing to a brighter future,” he said.

Other urban communities, such as Ryerson University, have also taken up the initiative to create a safe, healing space for Indigenous faculty members, staff and students.

Michael Mihalicz, the Indigenous advisor for Ryerson’s Ted Rogers School of Management, is working with staff and a few members from Ryerson’s Indigenous Advisory Circle to transform transform almost 12,000 square feet of “underutilized” space in the school’s courtyard into an Indigenous healing garden to improve students’ mental, physical and spiritual health.

Mihalicz says this is the first step in ensuring Indigenous students don’t feel as if they need to leave that part of themselves at home when they come to university. The project is still undergoing consultations from design teams about infrastructure details and landscape architecture.

“It’s really a way for us to honour those who came before by integrating Indigenous knowledge around the use of plant medicines to promote personal wellness directly into our campus planning while also providing usable green spaces for students to enjoy and addressing growing concerns around the wellbeing of our students,” he said.

Teekens looks over at the men scattered into groups of threes down on their knees planting cedar seeds. He breathes in the smell of fresh soil, the early spring breezetousling his hair. He thinks back to the 72 people who have been vaccinated at the centre. He knows he has a long way to go before he reaches his goal of trying to vaccinate every Indigenous person in Toronto. He doesn’t try to kid himself. He takes another deep breath, letting the cool air flow into his nose and lungs. The healing garden is a small step forward, but it is something. It is hope and that is the best thing he has right now.