By Gavin Axelrod

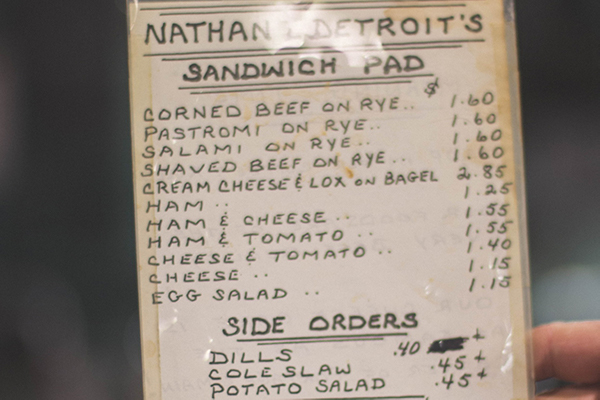

For 42 years Nathan Detroit’s Sandwich Pad has been a home away from home for its customers. But over the last year, the COVID-19 pandemic has left the once bustling 149-seat nook starving for the days of camaraderie, debate and laughter among its patrons.

It’s been a long time since familiar faces indulged in sandwiches held together by two pieces of soft rye bread and exchanged friendly banter with the staff. It would be easy for first-time customers of the underground, downtown Winnipeg restaurant to wonder if they had accidentally walked in on someone’s private family gathering.

If you’re lucky, your bacon and eggs will be sizzling as you slide through the clear glass doors and set yourself down on a brown leather chair.

“It feels like home (and) we treat people like they’re coming into our home … everybody knew everybody, it was first names, it was ‘Come on in’, it was hollering across the counter,” says Nathan Detroit’s general manager Brenlea Yamron.

Yamron runs the restaurant alongside her sister Karen Yamron-Shpeller and their mother Fraydel Yamron –– who, even at 77 years old, is still packing homemade soups.

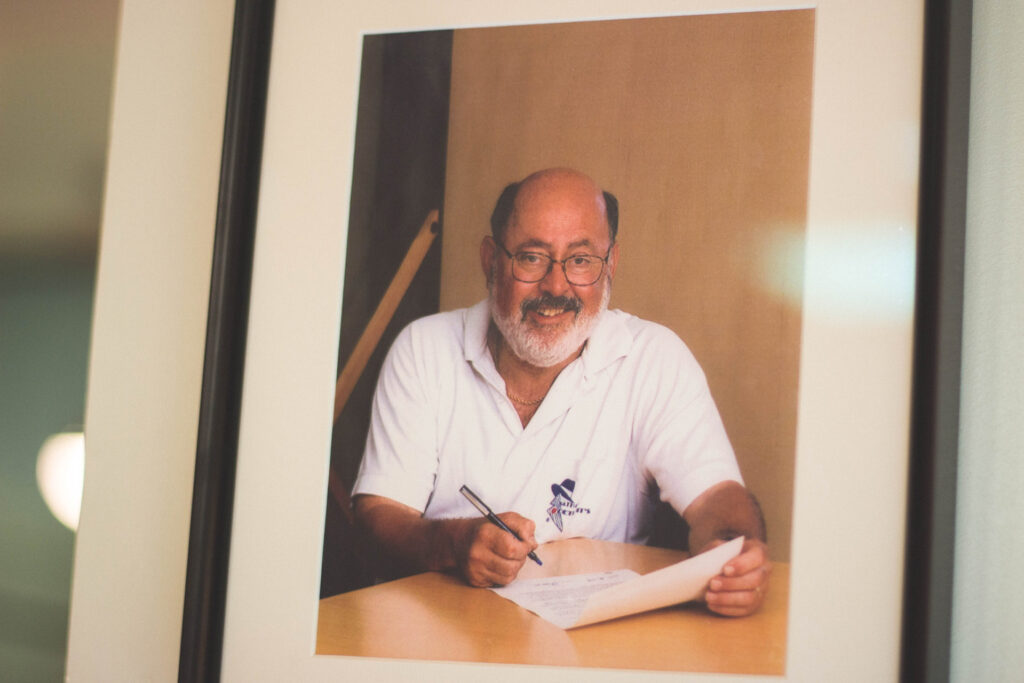

Fraydel and her late husband Ian (pictured right) purchased Nathan Detroit’s in 1981. He had no restaurant experience, but saw it as a perfect meeting place. Two decades later it’s become everything he imagined and more.

Brenlea says her father was the most positive person she ever met. His motto “and life goes on” echoes in her head while navigating the uncertain future.

“I know all through this pandemic he’d be saying, ‘Life ain’t fair. Oh well, next,’ ” she says

Brenlea started working full-time at Nathan Detroit’s when she was 17. She was 13 years old when her parents bought the restaurant, which meant she was old enough to fill in here and there.

Coffee and a cigarette was the snack of choice in those days for people looking to leave the stress of work in their office cubicle. Customers flocked to the restaurant as often as three times a day for a bite to eat and to hack a dart, leaving the place immersed in the smell of tobacco smoke.

Downtown culture is different now, the days of multiple coffee stops at the restaurant replaced with people filling up mugs at home or stopping at a drive-thru. You can’t smoke inside restaurants anymore either, but people will still light a cigarette, roll down their windows and let the frigid Winnipeg air creep into their cars during a morning commute. Brenlea is happy to leave her days of inhaling second-hand smoke behind as the restaurant and society have evolved.

It’s fitting that one of Canada’s most famous meeting places is located above “the deli,” as it’s referred to by family and friends.

The intersection of Portage Avenue and Main Street has always been a meeting place for Winnipeggers. It served as the rendezvous point during the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919 and is where hockey legend Dale Hawerchuck signed his contract in 1981.

Relationships are the backbone of Nathan Detroit’s existence and Yamron is proud the family has maintained some of its earliest connections. They still buy corned beef from Smith’s Quality Meats, now owned by Pratts Wholesale, the same supplier the restaurant used when it first opened.

Her neighbour growing up made the best cookies and her eyes light up with joy talking about how they’ve also become a favourite at Nathan Detroit’s.

The joy is short lived as she talks about the challenges the pandemic has created.

Nathan Detroit’s laid off staff for the first time ever last spring. Yamron’s face tightens as she relives the pain of having to tell 11 staff members, including a woman who worked there for 34 years, they’d no longer be employed.

“It feels like home (and) we treat people like they’re coming into our home.”

~ Brenlea Yamron

“We had our home family and our work family and here we were telling them that we were gonna not have them working for a couple of weeks, at the time we thought it was gonna be two weeks,” says Yamron.

“It’s very strange to have not seen that family for almost a year now.”

The restaurant adapted by offering curbside pickup, making catering orders pandemic-friendly and promoting its selection of homemade soups on social media. Brenlea and Karen’s day now consists of getting groceries at dawn, serving sandwiches at noon, mopping floors and making deliveries when needed.

Downtown Winnipeg can be an afterthought, unlike in Toronto where it’s a prime destination. Despite this, the Yamron sisters have ramped up the restaurant’s reach on social media. Karen says their social media following has increased, allowing them to attract customers outside the downtown area –– a goal since long before the pandemic.

As of March, in-person dining in Winnipeg is allowed at 50 per cent capacity, but table groups are limited to a single household and out of Winnipeg’s population of 825,000, only 16,800 actually live downtown.

“Everything that was positive about being where we’re located, being attached to 30 to 35,000 people within a couple of blocks, being in concentrated population … being indoors, all these things that were so positive are the exact negatives to COVID,” says Yamron.

As the clock strikes noon a modest lunch rush brings the restaurant to life. Brenlea takes a man’s order and recites it to her younger sister. Karen moves diligently behind the counter to slice salami and craft a handmade wrap.

During a brief break in the action, Brenlea delivers a piece of banana bread to one man, writes down another guest’s name for contact tracing and hollers across the floor that she’ll be right with the next customer. The six people dining-in serenade the space with friendly chatter –– a much better soundtrack than the motor of a hardworking drink cooler, which echoed throughout the restaurant 30 minutes ago.

For an hour the famous family-like atmosphere of Nathan Detroit’s is on display, but disappears almost as quickly as it began as the clientele carry on with their day.

As the snow begins to melt and Winnipeg warms up, the cold reality of a future without Nathan Detroit’s continues to creep in. The Yamrons are determined to work for the future of the restaurant, but need local support.

“If you have a dozen people spending $50 to $100 in a week, that could make a really big difference to the local guy who’s just trying to keep the lights on.”

The sobering truth for longtime local businesses like Nathan Detroit’s is there’s no guarantee of light at the end of the pandemic. Ever-mindful of their late father’s words, the Yamron sisters won’t let anything deter them.

After all, “Life goes on.”